Media Servers for Lighting Programmers

A Comprehensive Guide to Working with Digital Lighting

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Media Servers for Lighting Programmers

A Comprehensive Guide to Working with Digital Lighting

About this book

Media Servers for Lighting Programmers is the reference guide for lighting programmers working with media servers – the show control devices that control and manipulate video, audio, lighting, and projection content that have exploded onto the scene, becoming the industry standard for live event productions, TV, and theatre performances. This book contains all the information you need to know to work effectively with these devices, beginning with coverage of the most common video equipment a lighting programmer encounters when using a media server - including terminology and descriptions - and continuing on with more advanced topics that include patching a media server on a lighting console, setting up the lighting console for use with a media server, and accessing the features of the media server via a lighting console. The book also features a look at the newest types of digital lighting servers and products.

This book contains:

- Never-before-published information grounded in author Vickie Claiborne's extensive knowledge and experience

-

- Covers newest types of digital lighting servers and products including media servers, software, and LED products designed to be used with video

-

- Companion website with additional resources and links to additional articles on PLSN

-

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

CHAPTER 1

How Did We Get Here? A Brief Look at the Beginnings of Digital Lighting

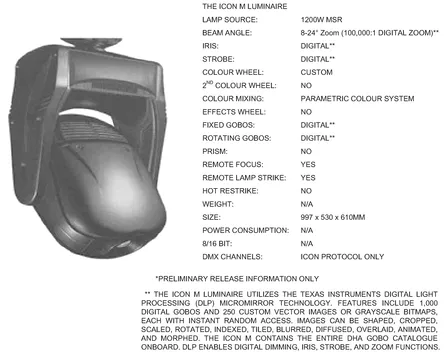

Icon M spec sheet.

Catalyst Orbital Head.

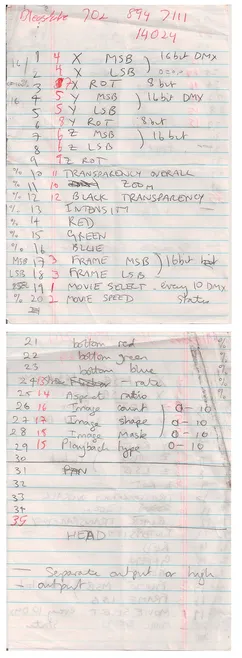

Early Catalyst notes. Source: Courtesy of Brad Schiller.

CHAPTER 2

Why Do LDs Want to Control Video from a Lighting Console?

Pros

- The lighting designer oversees the whole picture. What this means is that the LD can create more cohesive visual looks that combine lighting and video, and the execution of the cues will be tighter as well.

- Fewer hands in the mix. If the LD is calling the shots on how a video is played, there are fewer opportunities for missed cues or wrong videos at the wrong time.

- Simplification of control. Most media servers today can handle video camera inputs, switching, and audio output, for example. And if less video gear is needed during the show, fewer operators will be needed as well.

- Video clips can be manipulated in real time. This is a very important concept. Why? Because a pre-rendered video clip is what it is. When a video engineer plays it back using a standard video mixer, the video clip will play back exactly as it was rendered. Not so with a media server. The pre-rendered video clip is merely a suggestion of what the final composited image can be. A media server allows for real-time manipulation of video clips while being controlled from the lighting console. This means a virtually endless number of visual creations are possible because a piece of content can be affected via visual effects, color effects, size effects, etc, available both in the media server and in the lighting console.

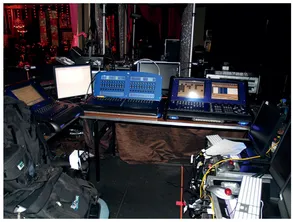

FOH lighting and video control.

Now for the Cons

- The limitations of the technology. Video equipment is highly specialized and therefore has been optimized to handle all of the tasks of video playback. Media servers and lighting consoles are digital solutions to video playback and are somewhat limited in areas including the number of video outputs, speed of accessing media, quality of output, and previewing a piece of video content. Best to know the limitations so there are no surprises on show site.

- Less time for a complete design of both elements. If an LD’s time is split between lighting and video for a performer like a big pop star, for instance, then he/she will likely not have much quality time to completely develop the cues for both. So it might be best in some cases to separate the responsibilities of video from lighting and return it to the video team.

- The workload for a single programmer to manage two time-consuming elements can be overwhelming. If one programmer is programming both lighting and video, then both may not be as thoroughly programmed and tight as they would be if the jobs were divided between two people. Therefore, it is very common on jobs where a media server(s) is being used to separate them out to a second lighting console and have a second programmer to focus strictly on the media servers.

CHAPTER 3

Convergence and the Role of the Lighting Programmer

The Responsibilities of the Media Server Programmer

- Budget

- Scale of show

- Programming and organizational abilities of the lighting programmer

- Trust in the lighting programmer to be able to handle the visual aspects of the production.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- A BIT ABOUT ME

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 1 How Did We Get Here? A Brief Look at the Beginnings of Digital Lighting

- CHAPTER 2 Why Do LDs Want to Control Video from a Lighting Console?

- CHAPTER 3 Convergence and the Role of the Lighting Programmer

- CHAPTER 4 Getting Familiar with Hardware

- CHAPTER 5 What Does that Piece of Equipment Do?

- CHAPTER 6 Programming a Media Server from a Lighting Console

- CHAPTER 7 It's All About the Content

- CHAPTER 8 Optimizing Content Playback from the Console

- CHAPTER 9 Content Gone Wild: Unexpected Playback Results

- CHAPTER 10 Video Editing Applications

- CHAPTER 11 Video Copyright Laws

- CHAPTER 12 Preparing for a Show

- CHAPTER 13 Networking Servers

- CHAPTER 14 Streaming Video

- CHAPTER 15 Managing Content across Multiple Outputs

- CHAPTER 16 Creative Raster Planning

- CHAPTER 17 Synchronizing Frames

- CHAPTER 18 3D Objects

- CHAPTER 19 Multi-Dimensional Controls

- CHAPTER 20 Pixel Mapping

- CHAPTER 21 Using Audio with Media Servers

- CHAPTER 22 Timecode, MIDI, and TouchOSC

- CHAPTER 23 The Evolution of Media Servers

- CHAPTER 24 Inside a Virtual Environment

- CHAPTER 25 DMX Controlled Digital Lighting

- CHAPTER 26 LED Display Devices

- CONCLUSION: Embracing New Technology

- APPENDIX A: Prepping for a Show: NYE in Las Vegas

- APPENDIX B: Common Troubleshooting

- APPENDIX C: Glossary

- APPENDIX D: Digital Lighting, Consoles, and Media Servers

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX