- 456 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

History of Urban Form Before the Industrial Revolution

About this book

Provides an international history of urban development, from its origins to the industrial revolution. This well established book maintains the high standard of information found in the previous two editions, describing the physical results of some 5000 years of urban activity. It explains and develops the concept of 'unplanned' cities that grow organically, in contrast with 'planned' cities that were shaped in response to urban form determinants. Spread throughout the texts are copious illustrations from a wealth of sources, including cartographic urban records, aerial and other photographs, original drawings and the author's numerous analytical line drawings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access History of Urban Form Before the Industrial Revolution by A.E.J. Morris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & City Planning & Urban Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 – The Early Cities

In the historical evolution of the first urban civilizations and their cities it is possible to discern three main phases. Each of these involved ‘radical and indeed revolutionary innovations in the economic sphere in the methods whereby the most progressive societies secure a livelihood, each followed by such increases in population that, were reliable statistics available, each would be reflected by a conspicuous link in the population graph’.1

The first of these phases covers the whole of the Palaeolithic Age, from its origins, at least half a million years ago, until around 10000 BC, followed by the proto-Neolithic and Neolithic Ages. These in turn lead to the fourth phase, the Bronze Age, starting between 3500 and 3000 BC and lasting for some 2,000 years. During this last period the first urban civilizations were firmly established.

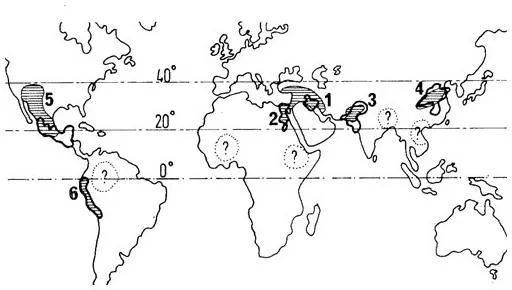

In his most valuable book The First Civilisations: The Archaeology of their Origins, Dr Glyn Daniel states that ‘we now believe that we know from archaeology the whereabouts and the whenabouts of the first civilisations of man – in southern Mesopotamia, in Egypt, in the Indus Valley, in the Yellow River in China, in the Valley of Mexico, in the jungles of Guatemala and Honduras, and the coastlands and highlands of Peru. We will not call them primary civilisations because this makes it difficult to refer to Crete, Mycenae, the Hittites, and Greece and Rome as other than secondary civilisations and this term secondary seems to have a pejorative meaning. We shall talk rather of the first, the earliest civilisations, and of later civilisations’. Figure 1.2 gives the locations of these seven original urban civilizations and relates them to the earliest known, or assumed, agricultural regions.2

Figure 1.2 – The location of the first civilizations (in heavy outline) related to the location of the earliest known agricultural communities (the hatched areas) and possible other early agricultural centres. Key: 1, Southern Mesopotamia (Sumerian civilization); 2, Nile valley (Egyptian); 3, Indus valley (Harappan); 4, Yellow River (Shang); 5, Mesoamerica (Aztec and Maya); 6, Peru (Inca). The lines of latitude 20° and 40° north of the Equator contain five of the first civilizations.

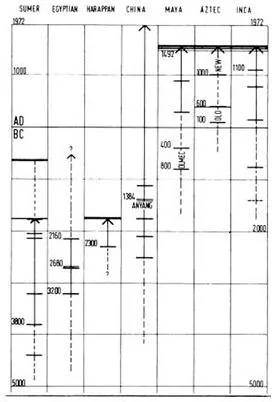

As shown by the time chart (Figure 1.1), the seven civilizations occurred at markedly different times. The first three – the Mesopotamian, the Egyptian, and the Indus Valley – are the so-called ‘dead’ cultures, out of which there evolved, in direct line of descent, the Greek, Roman and Western European Christian civilizations. Mesopotamia is also of fundamental importance for its formative influence on the evolution of urban settlement in the Arabian Peninsular, where Islamic culture originated in the seventh century AD.3

Figure 1.1 – Time chart showing the comparative dates of the seven first civilizations.

Although occurring much more recently than Chinese civilization, the fourth oldest, the three American cultures – Mexican, Central American and Peruvian – are also dead: brutally destroyed by Spanish conquistadores during the decade or so after 1519. ‘There, in the sixteenth century,’ writes Daniel, ‘Europe met, if not its own past, at least a form of its past’,4 where, for example, metal technology was either extremely limited or yet to be discovered.5

China is the fascinating exception, from its origins in the Yellow River basin during the late third millennium BC, its culture has lasted to the twentieth century without permanent interruption. Furthermore, during the eighth century AD – one of its peaks of power and influence – Chinese urban civilization was introduced into Japan, where until then only essentially agricultural settlements had existed.

This chapter will deal with the origins, and describe key examples of the urban settlements of three of the earliest civilizations: first, the Sumerian civilization of the Tigris/Euphrates floodplains of Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) – with post-scripted extension through into the adjoining Arabian Peninsular; second, the Egyptian civilization of the Nile Valley and Delta; and third, the Harappan civilization of the Indus Valley.

Urban origins in Mexico (the Aztecs), Central America (the Maya) and Peru (the Incas) are included in Chapter 9 (Spain and her Empire). The continuing Chinese civilization is summarized in Appendix A; Appendix B describes the related origins of urban settlement in Japan, through to that country’s industrial revolution commencing in the second half of the nineteenth century. Urban beginnings in Europe generally, and Britain in particular, are dealt with in Chapter 4 as part of the background to the European medieval period.

In some parts of the world, notably North America, Australasia and southern Africa, European urban culture was either introduced into uninhabited territories, or imposed on indigenous peoples. There are still a few remotely isolated societies which, left to their own devices, are no further advanced than the Palaeolithic phase.

This account of the origins of cities is based on the ordinarily accepted belief that the development of settled agriculture was the essential prerequisite for the evolution of urban settlements. In the late 1960s this doctrine was challenged by Jane Jacobs, who pronounced ‘the dogma of agricultural primacy is as quaint as the theory of spontaneous combustion … in reality agriculture and animal husbandry arose in cities’, on which basis, it was claimed that ‘cities must have preceded agriculture’.6 Jane Jacobs had devised that theory in support of her short-lived personal interpretation of economic failings of later twentieth-century American cities, which sought to gain historical support from the recently published archaeological findings of James Mellaart at Çatal Hüyük, in Anatolia.7 This extraordinary site was seemingly qualified for ‘urban’ status by the seventh millennium BC – perhaps even earlier, thus anticipating the beginnings of Mesopotamian civilization by 3,000 or more years. Jericho, of comparably ancient origin, has also occasioned controversy. The significance of these two exceptional settlements is assessed later in the chapter, with the summary argument against the theory of urban primacy.

It is impossible to make an exact determination of the world’s population in remote ages because firm data cannot be established. Nevertheless, scientists have done their best. Here is a recent estimate, rough as it necessarily is (E S Deevey, Human Population, Scientific American, September 1960, pp. 195–6):

Prehistoric world population

Lower Paleolithic (1,000,000 years ago)

125,000

Middle Paleolithic (300,000 years ago)

1,000,000

Upper Paleolithic (25,000 years ago)

3,340,000

Mesolithic (before 10,000 years ago)

5,320,000

If these figures are even fairly correct, there were little more than five million human beings when the hunting and food-gathering phase of mankind’s existence reached its full development. The long, slow increase in population was brought about by improved weapons, better hunting techniques, and more capable methods of dealing with cold weather, predatory beasts, and other natural threats to existence. Getting more food made it possible for more people to stay alive and breed even more people.

(P van Doren Stem, Prehistoric Europe)

Early settlements

Human-like creatures first appear on the earth perhaps as long as 1 million years ago, and become ‘dispersed from England to China, and from Germany to the Transvaal’.8 By about 25000 BC the physical and organic evolution of Homo sapiens is considered to have come to an end and the modern processes of cultural evolution start.

Most of the major technological innovations of antiquity were made within the limited area of the Near East and the eastern end of the Mediterranean, and little could be more fatal than imagining that those regions were in antiquity as we know them today. Even in the past ten thousand years enormous changes have taken place which owe nothing to population changes (either migrations or explosions), nor to the recent development of cities, roads and railways. Far more fundamental is that fact that the entire ecology of the region has undergone drastic changes. What we know today as open, dusty plains or rich farmlands were, ten thousand years ago, more or less thickly forested, and within the forest lived a wide variety of wild animals. This is not to say that deserts did not exist, but rather that many hills that we know of today as barren ranges of rock were then at least lightly covered with trees, while the river valleys probably carried very dense forest cover.

(H Hodges, Technology in the Ancient World)

From their first appearance, down to the beginning of the Neolithic Age, humans existed on much the same basis as any of the other animals, by gathering naturally occurring foodstuffs in the form of berries, fruits, roots and nuts and, somewhat later, by preying on other animals and by fishing. The social unit was the family, but the society was of necessity a mobile one, always having to move to fresh sources of food, carrying its few possessions from one crudely fashioned temporary shelter to another. There was no permanent physical unit about 14000BC when ‘as the last great ice age was approaching men were sufficiently well equipped to evict other denizens and themselves to find shelter in caves. There we find true homes’.9 Permanence of residence was, however, determined by the continuing availability of food within reach of the ‘home’.

Professor Childe notes that this gathering economy corresponds to what Morgan10 calls savagery and that it ‘provided the sole source of livelihood open to human society during nearly 98 per cent of humanity’s sojourn on this planet’.11 Such an economy imposed a limit on population with a direct relationship to the prevailing climatic and geological conditions. The entire population of the British Isles around 2000 BC has been put by Childe at no more than 20,000, with an increase to a maximum of 40,000 during the Bronze Age. In France the Magdalenian culture between 15000 to 8000 BC, with at first exceptionally favourable food resources, had a maximum population density of one person per square mile, with the general figure around 0.1 to 0.2.12 Other examples given by Childe are that ‘in the whole continent of Australia the aboriginal population is believed never to have exceeded 200,000 – a density of only 0.03 per square mile’,13 while on the prairies of North America he quotes Kroeber’s estimate that ‘the hunting population would not have exceeded 0.11 per square mile’.14

Somewhere around 8,000 to 10,000 years ago humankind started to exercise some measure of control over the supply of food by systematic cultivation of certain forms of plants, notably the edible wild grass seeds, ancestors of barley and wheat, and by the domestication of animals. ‘The escape from the impasse of savagery was an economic and scientific revolution that made the participants active partners with nature instead of parasites on nature.’15 This Neolithic agricultural r...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- 1 – The Early Cities

- 2 – Greek City States

- 3 – Rome and the Empire

- 4 – Medieval Towns

- 5 – The Renaissance: Italy sets a pattern

- 6 – France: Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries

- 7 – A European Survey

- 8 – Britain: Sixteenth to mid Nineteenth Centuries

- 9 – Spain and her Empire

- 10 – Urban USA

- 11 – Islamic Cities of the Middle East

- Appendix A – China

- Appendix B – Japan

- Appendix C – Indian Mandalas

- Appendix D – Indonesia

- Appendix E – Comparative Plans of Cities

- Select bibliography

- General Index

- Index of Place Names