![]()

CHAPTER

1

NEW MODELS OF DEEP COMPREHENSION

Arthur C. Graesser

Shane S. Swamer

William B. Baggett

Marie A. Sell

University of Memphis

This chapter presents new models of comprehension that we have been developing in recent years. These models focus on deeper levels of comprehension (which involve pragmatics, inferences, and world knowledge) rather than shallow levels of comprehension (such as lexical processing, syntactic parsing, and the interpretation of explicit text). Early research in the psychology of language and discourse processing emphasized the shallow levels of comprehension. It was easier to measure and manipulate factors directly associated with the surface text than to struggle with barely visible mechanisms at the deep levels. There were many theories about the surface levels, enough theories to occupy everyone’s time for several decades. However, researchers came to recognize the pressing need to explore the deep levels. They discovered that the deep levels often have a greater impact on reading time, memory, decision making, and judgment than do the shallow levels. They also identified interesting ways in which deep levels interacted with shallow levels of processing. The zeitgeist has shifted from the shallow to the deep levels of comprehension.

The research reported in this chapter investigates three rather diverse components of deep comprehension: dialogue patterns, generation of knowledge based inferences, and question asking. Each of these components has interested researchers in discourse processing and natural language comprehension, but adequate psychological theories have not yet evolved. This chapter attempts to fill the void by sketching new models that explain the systematicity within each of these three components. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to cover all of the literature on dialogue patterns, inference generation, and question asking. Instead, this chapter is designed to sketch new models, report selected empirical support for each model, and identify promising directions for expanding the models.

DIALOGUE PATTERNS: PREDICTING THE NEXT SPEECH ACT CATEGORY

The content of many conversations seems very predictable. For example, consider the following initial exchange of a telephone conversation:

Art (after the telephone rings):Hello.

Shane:Is this Art?

Art:Yeah. Oh, Shane! How’s it going?

Shane:Oh, pretty good.

Art:So what can I do for you?

Shane:I have a question about this one analysis. …

There are clear expectations about which speech acts are appropriate at each turn. The conversation would be incoherent if the same speech acts were randomly ordered. When person A asks a question, person B is expected to formulate a reply to the question. A promise from person A normally elicits gratitude from person B. A greeting elicits a counter-greeting or acknowledgment. Conversation patterns are very regular (if not completely scripted) during greetings, introductions, business transactions, restaurant conversations, and most other speech exchanges. This systematicity is not confined to speech. There are vestiges of these regularities in the rhetorical structures embodied in narrative text and even in expository text.

Researchers in discourse processing, sociology, and sociolinguistics have analyzed prominent dialogue patterns (Clark & Schaefer, 1989; D’Andrade & Wish, 1985; Goffman, 1974; Graesser, 1992; Mehan, 1979; Schegloff & Sacks, 1973; Turner & Cullingford, 1989). Some of the systematicity resides at a categorical level that is independent of the world knowledge, beliefs, and goals of the speech participants; that is, there are appropriate and inappropriate orderings of speech act categories. Schegloff and Sacks (1973) analyzed the adjacency pairs of conversational turns to answer the following question: Given that one speaker utters a speech act in category C during turn n, what is the appropriate speech act category for the other speaker at the next, adjacent turn (n + 1)? The most common adjacency pair is the [Question → Reply-to-question] sequence. The adjacency pair analysis considers only one speech act as prior context when generating predictions for the subsequent speech act. However, researchers have identified larger sequences of dialogue patterns. Mehan (1979) identified a triplet that occurs frequently in classroom environments, which is illustrated in the following sequence:

Teacher question:What is the capital of Florida?

Student answer:Athens.

Teacher evaluation of answer:No, that’s not right.

Counter-clarification questions produce a quadruple sequence:

Question A:Where did you go yesterday?

Question B:Yesterday morning?

Answer B:Yeah, in the morning.

Answer A:To Jack’s, for breakfast.

There are longer sequences of dialogue patterns, but the longer sequences have rarely been investigated.

The knowledge accumulated in the study of dialogue patterns has been fragmented and largely untested. No one has developed a model that ties together the assorted observations. No one has quantified the extent to which these patterns account for the speech acts in naturalistic conversation. There is no model that is sufficiently broad in scope that it could be applied to any conversation or text. In view of these shortcomings, we developed two models that attempt to capture the systematicity in speech act sequences. The two models have radically different computational architectures: a connectionist architecture and a symbolic architecture.

The two models are based on the assumption that the stream of conversation (or text) can be segmented into a linear sequence of speech act categories. There have been extensive debates over what speech act categories are needed for a satisfactory analysis of human conversation (Austin, 1962; Bach & Harnish, 1979; D’Andrade & Wish, 1985; Searle, 1969). We adopted a slightly modified version of D’Andrade and Wish’s (1985) set of speech act categories. Their categories were both theoretically motivated and empirically adequate in the sense that trained judges agreed on the assignment of categories. The eight categories of speech acts are:

1. Question (Q): Interrogative expression that is not an indirect request (e.g., “What is your name?”).

2. Reply to question (RQ): Speech act that answers a previous question (e.g., “My name is Marie.”).

3. Directive (D): A request in an imperative form for the listener to do something (e.g., “Shut the door.”).

4. Indirect directive (ID): A request in a nonimperative form for the listener to do something (e.g., “Could you shut the door?, I would appreciate it if you’d shut the door.”).

5. Assertion (A): A report about some state of affairs that could be true or false, but does not directly answer a previous question (e.g., “I went to Minneapolis last week., Minnesota is cold in March.”).

6. Evaluation (E): An expression of sentiment or judgment about some entity, fact, event, or state of affairs (e.g., “That’s ridiculous!, That’s right.”).

7. Verbal response (R): A spoken acknowledgment of the previous speech act by the other person (e.g., “Uh-huh.”).

8. Nonverbal response (N): A nonverbal acknowledgment of the previous speech act by the other person (e.g., a head nod).

Because there are two speakers in a dialogue, each speech act in a conversation can fall into one of 16 categories (2 speakers × 8 basic speech acts = 16). A Juncture (J) category was also included to signify lengthy pauses in a conversation and excerpts that are uninterpretable to judges. In summary, the stream of dyadic conversation was segmented into a sequence of speech acts and each speech act was assigned to 1 of 17 speech act categories.

Sell et al. (1991) used this 17-category speech act scheme in their analysis of 90 conversation involving pairs of children. Dyads of second-graders and sixth-graders were videotaped for 10 minutes in three different contexts: playing 20 questions, solving a puzzle, and free play. The dyads were further segregated according to how well they knew each other: mutual friends (A and B liked each other), unilateral friends (A liked B, but B neither liked nor disliked A), and acquaintances (A and B did not like or dislike each other). All of the children in the dyads were from the same classroom and so they were never strangers. Sell et al. (1991) reported that the 17-category speech act scheme could be successfully applied to the 16,657 speech acts in this corpus (hereafter, called the “Sell corpus”). The 17 categories were sufficient in that all of the speech acts in the Sell corpus fit into one of the 17 categories. The categories were sufficiently reliable because trained judges agreed on which category to ascribe to the speech acts; the Cohen’s kappas were .82, .76, and .74 for the question, puzzle, and free-play task, respectively.

The goal of our models was to capture the systematicity in the sequential ordering of the speech act categories. That is, to what extent can the category of speech act n + 1 be successfully predicted, given the sequence of speech acts 1 through n? A hit rate is the likelihood that a theoretically predicted category actually occurs in the data, as specified in Formula 1.

A hit rate is not a satisfactory index of the success of a model, however, because it is not adjusted for the likelihood that the speech act could occur by chance. For example, if a particular speech act category occurred in the corpus 90% of the time, there would be a high hit rate, assuming that the model predicted that category most of the time. A satisfactory index of the success of the model would need to control for the baserate likelihood that the predicted speech act occurred in the empirical distribution of speech act categories (called the a posteriori distribution). For example, the baserate likelihoods of the speech act categories in the Sell corpus were .21, .14, .04, .02, .40, .03, .07, .03, and .07 for categories Q, RQ, D, ID, A, E, R, N, and J, respectively. We computed a goodness-of-prediction (GOP) index that corrected for the baserate likelihood that a speech act category would occur by chance, as specified in Formula 2.

The model allows for more than one speech act category at observation n + 1. In this case, Formulas 1 and 2 are still correct except that the values are based on a set of categories rather than a single category.

Recurrent Connectionist Network

Researchers in the connectionist camp of cognitive architectures developed a recurrent network that is suitable for capturing the systematicity in the temporal ordering of events (Cleeremans & McClelland, 1991; Elman, 1990). The recurrent connectionist network preserves in the network an encoding of all previous input, and uses this information to induce the structure underlying temporal sequences.

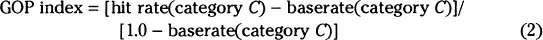

There are four layers of nodes in the recurrent network, as shown in Fig. 1.1. The input layer specifies the category of speech act n. There are 17 nodes in the input layer, one for each speech act category. The appropriate node is activated when speech act n is received. For example, if Person 1 asked a question, then the Q1 node would be activated in the input layer of the network. The output layer contains the predictions for speech act n + 1. There are 17 output nodes, one for each speech act category. An output node has an activation value that reflects the degree to which the network predicts that output node. For example, if the input were Q1 we would expect RQ2 to receive a high activation value in the output layer, thereby capturing the regularity that people are expected to answer questions that others ask. The hidden layer captures higher order constituents that are activated by speech act n. Hidden layers are frequently implemented in connectionist architectures to capture internal cognitive mechanisms (Rumelhart & McClelland, 1986). The hidden layer is needed when direct input–output mappings fail to capture systematicity in the data. There are 10 nodes in the hidden layer of our network. The context layer allows the network to induce temporal sequences. The context layer stores the activations from the hidden layer of the previous step in the speech act sequence (as designated by the fixed weights of 1 in Fig. 1.1). The activations of the hidden layer at step n depend on: (a) the input at n and (b) the activation of the context layer at n (which was the hidden layer at n −1). Therefore, the hidden layer is receiving information about present and past inputs. The resulting activation pattern of the 10 nodes of the hidden layer at step n is subsequently copied into the context layer at step n + 1. The context layer must have the same number of nodes as the hidden layer (10 nodes in our model).

FIG. 1.1. Recurrent connectionist network for speech act prediction.

There are a total of 440 connections that are allowed to vary in the weight space of this model. There are 170 connections between the input layer and the hidden layer (i.e., 17 input nodes and 10 hidden layer nodes). Similarly, there are 170 connections from the hidden layer to the output layer. The other 100 nodes link the 10-node context layer to the 10-node hidden layer. There are also connections from the hidden layer to the context layer that are fixed at 1. In preliminary simulations, we varied the number of nodes in the hidden layer and the context layer (from 6 to 14 nodes). However, the success of the model did not depend on the number of nodes in these layers.

The recurrent connectionist network was used to simulate predictions for the 16,657 speech acts in the Sell corpus (see Swamer et al., 1993). The network was trained on 12 passes through the corpus (i.e., the performance of the network had clearly settled and reached an asymptote). We performed eight different simulations, with each run having a different set of random initial weights in the weight space. Performance measures were averaged over these eight simulations.

The performance of the recurrent network was evaluated by computing two different GOP indices (see Formula 2). A maximal activation GOP index considered only one output node as the predicted speech act category for step n + 1. The predicted category was the one that received the highest activation value in the output layer. The maximal activation GOP index was found to be .29. The hit rate in this analysis was .38 and the b...