![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Sacred space constitutes itself following a rupture of the levels which make possible the communication with the trans-world, transcendent realities. Whence the enormous importance of sacred space in the life of all peoples: because it is in such a space that man is able to communicate with the other world, the world of divine beings or ancestors.

(Mircea Eliade)1

“How long wilt thou hide thy face from me?”2 David cries in Psalms, a plaintive expression of the enduring religious theme of separation from the divine. “Why dost thou stand so afar off, O Lord?”3 he asks, his question framing the perennial human condition of dislocation from larger contexts, broader knowledge, and deeper understandings. The disconnections may be spiritual, but they are often described spatially. In Taoism, the immortal gods reside on islands separated by vast waters. In Buddhism, unenlightened states are a “middle world” and texts describe a “crossing over” from delusion to enlightenment. In the first book of the Hebrew Bible, Adam and Eve are expelled from the place where God dwells and are separated by a gateway blocked by “cherubim and a flaming sword which turned every way.”4 The Christian Gospels contain a number of references to gateways and thresholds, physical boundaries that both separate and connect one to the divine. As Jesus asserted: “The gate is narrow and the way is hard that leads to life, and those that find it are few.”5

What is required to bridge these seemingly unbridgeable gaps – to cross these narrow thresholds? This book argues that sacred architecture was conceptualized, realized, and utilized as a response to this eternal question, and believed to connect what was formerly discontinuous.

1.1

The Magic Circle, John William Waterhouse, 1886

Source: Tate Gallery, London/Art Resource, New York.

The Mediating Roles of Religion and Architecture

Religious traditions insist that connections to deeper ways of being in the world are only possible through belief and participation in religion. The “holy” is the “whole” – the re-connection of humans with their god(s). Religious beliefs and practices from around the world, in all their variety, share the goal of connecting the individual to broader communal, cultural and theological contexts. The root word of religion is reliquare, “to bind together,” suggesting its principal role of establishing connections with the divine. Hinduism views the ordinary world as maya, a scrim of illusion withdrawn only through the perspectives that religion provides. The term yoga means “to yoke” or “to bind together,” and yogic practices served to join the separate individual with the universal “self.” Religion, in this context, is a mediator, its beliefs and rituals serve to interconnect the individual, the community, the understandings they seek, and the gods they worship.

1.2

Religion is a mediator, its beliefs and rituals serve to interconnect the individual, the community, the understandings they seek, and the gods they worship. Annunciation, Piermatteo d’Amelia, c. 1475

Source: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

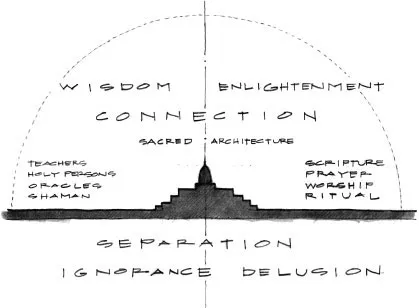

The principal argument of this book is that sacred architecture typically articulated an intermediary “position in the world” that was both physical and symbolic. Religion has traditionally articulated questions regarding the meaning and significance of human existence and mollified feelings of isolation and alienation. It has been intrinsic to the archetypal human endeavor of establishing a “place” in the world. Architecture has incorporated similar agendas – providing shelter, a meaningful place that embodies symbolic content, and a setting for communal rituals. Humans are unique because they are not only part of their environment, but actively and deliberately shape it – often in the service of cultural, socio-political, and religious imperatives. Sacred places were often precisely built at specific locations with the hope that connections would result and the otherwise inaccessible accessed. Throughout the book, I argue that sacred architecture performed, and in some cases continues to perform, a critical role in embodying religious symbols and facilitating communal rituals – with the goal of creating a middle ground, a liminal zone, that mediates between humans and that which they seek, revere, fear, or worship.

Religion and religious figures have traditionally been put into the service of mediating between humans and the knowledge or understanding they seek or the gods they worship. Similarly, sacred architecture was conceptualized and created as a physical and symbolic mediator, often in support of the religions it was built to serve. Just as scripture and mythology often describe the promise and potential of religion to join, to connect, to unveil, these themes were also symbolized by sacred architecture. In this context, analogous to scripture, prayer, worship, teachers, holy persons, oracles, shamans, and other mediums, sacred architecture was (and often still is) an intermediate zone believed to have the ability to co-join religious aspirants to what they sought. Moreover, communal rituals, as embodiments of myth, scripture, and belief, were another means of connection where the architectural settings were vivified and completed. All were (and are) in-between places believed to provide bridges across liminal realms.

1.3

The sacred place was (and often still is) an intermediate zone believed to have the ability to co-join religious aspirants to what they sought. The Western Wall, Jerusalem

1.4

Analogous to scripture, prayer, worship, teachers, holy persons, oracles, shamans, and other mediums, sacred architecture was (and often still is) a means to establish revelatory links

Context and Scope

This book positions architecture as a cultural artifact that responds to its social, political, economic, and environmental contexts and expresses a complex matrix of cultural beliefs and imperatives. In this context, it is presented as a communicative media that embodies symbolic, mythological, doctrinal, socio-political, and, in some cases, historical content. Moreover, it is often an active agent that performs didactic, elucidative, exhortative, and, in some cases, coercive roles.

The language or media of architecture serves to communicate its symbolic content to establish its often multiple, complex meanings. Central to the legibility of architecture is the active engagement it requires. One “reads” its content through deciphering its language to construct its meaning.6 And because this engagement is context-dependent, this study includes pertinent social, cultural, political, historical, environmental, and liturgical settings that helped to shape the architecture. It recognizes that the deciphering of the symbolism of architecture often leads to deeper understandings of the culture that built it, and understanding its full context is essential to deciphering its meaning. Even though its meanings are often complex and subject to multiple interpretations, what we at times discover is the capacity of architecture to reveal a culture is equal to or exceeds textual or historical evidence.7

One early role of religion was to bind together a clan, tribe, nation, or culture in support of territorial and hierarchical agendas, which is why (both positively and negatively) religion, culture, and place are so inextricably connected. Architecture typically served these unified and multifarious cultural, religious, and territorial agendas. Even the most primordial of architectures, the burial mound, served to reinforce the continuity of the clan, the hierarchy of its leaders, and its territorial claims. Religious sites and edifices were rarely benign and typically served the political and social agendas of the organized societies that built them. The dark side of the declarative and didactic roles of architecture is its complicity in the reinforcement of social dictates and hierarchies. However, the incorporation of architecture’s role in social coercion and territorial restriction in histories and theories of architecture can serve to deepen our understandings of its cultural significance. It can reveal the power that architecture did (and still does) possess.

This book establishes broadened contexts, approaches, and understandings of architecture through the lens of the mediating roles performed by sacred architecture. It examines a specific stratum of the layers of architectural history to provide heterogenous readings of its experiential qualities and communicative roles. I focus on sacred architecture because this particular “type” provides arguably the most accessible and diverse means to unpack the meaning and symbolism of architecture. In particular, sacred architecture was often the result of significant human and material resources – an indication of the value that it held. The book’s focus, however, does not imply that other types of architecture do not perform partial or similar roles in particular settings. Some may – or may provide additional means and media of communication and engagement – but are outside of the scope of this study.

Definition of Terms

The term sacred architecture defines places built to symbolize the religious axioms and beliefs, communicate socio-political content, and accommodate the rituals of particular cultures within their specific historical settings. God, or the gods, is used both specifically and generally. In some cases, the religious and architectural orientation is toward a singular god – in others, the gods are diffuse or multiple. The term divine is applied to include objects of veneration or worship, such as divine ancestors or wisdom. Content refers to the symbolism embodied by the architecture, whereas meaning is the outcome of individual or collective understandings that result from participation in or with the architecture. Additionally, a symbolic language is the convention used to embody the symbolic content, which is also described as communicative media – all of which constitute an inclusive definition of symbolism.

The definitions and etymology of the term mediate and words related by meaning, use, and their roots, are necessary to establish our scope of inquiry. Mediate comes from the Latin mediare, which means to be “in the middle,” and its Germanic root, midja-gardaz, means a “middle zone” that lies between heaven and earth. Mediate is an active verb that describes actions for bringing together separate parties, producing results, or synthesizing information. As such, it is understood as a dynamic activity that oscillates between discrete entities. Related terms include mediating, mediator, media, mean, medial, median, mediant, and medium, all of which include space and spatial relationships.

The act of mediating is to serve as an intermediary between separate positions. Mediation, in its current use, is a form of conflict resolution where a mutually agreed-upon solution is facilitated, but not imposed, by a third-party mediator. This definition is useful because of the necessity of participation of the separate parties to reach a conclusion. (The other current form of conflict resolution is arbitration where the third-party arbitrator provides a binding final decision, most likely favoring one of the petitioners and aptly called an “award.”) These roles are distinguished from those of a medium, an agency (such as a person or material) through which something is accomplished. In the case of a person, a medium has the ability to connect otherwise inaccessible worlds, most popularly to communicate with the dead, as in a psychic medium. Turning to words that have more direct material and spatial implications, we note that a medium is also an environment where cultures or other growths can thrive or even a substance that acts between other substances, as in the use of a solvent medium in painting. In geometry, the median is the line that connects the vertex of a triangle to the midpoint of its opposing side – in anatomy, it is the line that divides bodies into two symmetrical parts. In mathematics, the arithmetic mean is a value at the center of all described values. Lastly, media (which is related to medium) is the means of communication and connection. Its current use defines all the means utilized to communicate information or content and print and broadcast media are the most common usages of this term. However, we should recognize that their hegemony is a rather recent development and that the media of the arts and architecture were at times predominant. That is why sacred architecture is often the most effective way to understand the beliefs of the religions that created it.

Aims of the Book

This book aims to contribute to the body of knowledge concerning the dynamic interactions sacred architecture requires, as well as its symbolism, ritual use, and cultural significance. Its intentions include framing broadened understandings of architecture. It positions architecture as a cultural artifact that expresses and influences the preoccupations, prejudices, values, and aspirations of the communal human endeavors we (inadequately) call culture. To do so, the book includes philosophical traditions that analogously express and influence cultural self-definitions and activities, and compares them to other cultural outputs – primarily religious beliefs and practices but also other creative media. It argues that architecture, like any communicative media, employs language that is accessible to a critical mass of participants while retaining sufficient nuance and variability of interpretation to facilitate personal resonances and connections. It recognizes that the language of architecture is primarily formal and scenographic and that through this media architecture is referential – leading one to connections with related cultural outputs, and thus contributing to individual and communal elucidation. It also suggests that because architecture provides the setting for communal activities, it consequently supports the most potent of human endeavors, the shared cooperative pursuit of knowledge, understanding, consciousness, and improvement.

In this book I focus on the more interstitial, hidden, and mysterious aspects of architecture to argue that traditionally it served as a media that incorporated and communicated content, engendered emotional and corporal responses and served to orient one in the world. This theoretical approach is consistent with more nuanced and multivalent understandings of architectural form and space, and includes a much broader context within which architecture performs and is experienced. It recognizes the power of architecture to re-veal (“un-veil”), to elucidate, and to transform – a concept intrinsic to architecture in the past, often misunderstood in the modern era, and essential that we reconsider today.

Theoretical Approaches

How do we effectively frame the issues and cogently establish reliable understandings of a cultural output as complex, nuanced, and ineffable as sacred architecture? First of all, we need to clearly establish the scope and limitations of our study and our methods of interpretation. Overall, I adopt philosophical approaches to understanding architecture, for, in the words of Hans-Georg Gadamer, “where no one else can understand, it seems that the philosopher is called for.”8 More specifically, I utilize comparative and intersubjective perspectives to synthesize a broad range of cultural contexts and the diverse communicative media, socio-political and religious agendas, and ritual uses of sacred architecture. It is in the “in-between” of the complex forms, media, agendas, and ritual uses that constitute sacred architecture that new understandings, from a contemporary perspective, might be gained. In this context, hermeneutical interpretive methodologies are put in the service of conceptualizing a “middle ground” of understandings and a holistic examination of predominant themes in sacred architecture. The process of analyzing certain aspects of the cultural outputs of the past, and applying current thinking to them, may establish i...