![]()

1

Goals and Distinctive Characteristics of This Survey

How shall we know sleep? Since the broad adoption of polysomnography (PSG), this question is not asked often enough, and is too often answered with buoyant self-assuredness.

The scientific journey of Werner Heisenberg (Cassidy, 1992) provides some perspective on how to answer this question. Like Pavlov before him, Heisenberg was a Nobel laureate, but were that his main accomplishment, he would be lost in the oblivion of history. Pavlov achieved fame not by winning the Nobel prize for his studies of the digestive processes of dogs, but as an afterthought of that research: deriving principles of conditioning that explained the behavior of dogs and others (Windholz, 1997). Heisenberg was a German physicist, and his prize was for contributions to the theory of quantum mechanics. As part of that research program, he was frustrated in his attempts to study atomic particles because the light needed to illuminate the subject altered the path of the electrons. Thus was born Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle: The act of measurement alters what one wishes to measure, rendering specific knowledge indeterminate.

Sleep scientists in the main are probably not very sympathetic to Heisenberg’s complaint. How much error could light particles have introduced to the study of electrons compared to our routine procedures? Our standard protocol is to remove individuals from their accustomed surroundings, mount a dozen or more sets of electrodes with glue, tape, straps, clips, and the like from head to foot, and then put them to rest in an uncomfortable hospital bed. It is well established that the sleep laboratory setting alters sleep, as shown by disturbed sleep the first night in the laboratory (i.e., first night effect; Kales & Kales, 1984) and laboratory–home recording comparisons (Edinger et al., 1997; Stepnowsky, Moore, & Dimsdale, 2003). With the ease and confidence of a stand-up comic, the sleep technician instructs the individual to sleep naturally. Heisenberg didn’t know how good he had it.

We could prove that PSG alters sleep by comparing it to a known accurate measure of sleep, but PSG is the gold standard against which other methods of sleep assessment are judged. Considering commonplace alternatives to PSG, the worthiness of actigraphy, inferring sleep from limb inactivity, or self-report (SR) sleep is evaluated by how closely they match PSG data. Of course, the matches are never perfect and assignment of fault is in part determined by convention (i.e., because PSG is objective, it is always best) and in part by philosophy of science (e.g., greater faith is assigned SR sleep in the unperturbed natural environment because it maximizes ecological validity).

Perhaps we shall never know sleep, only representations of it blurred by intrusive and/or fuzzy measures. Certainly for the present, no method of measuring sleep spares the subject of our interest. The best we could aspire to is to choose a method whose profile of strengths and shortcomings seems to closely fit the circumstances and goals of a particular clinical or research evaluation. In these endeavors, we should be humbled by the implications of Heisenberg’s admonition that at all times, the relationship between sleep data and sleep is uncertain.

GOALS OF THE PRESENT EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SURVEY

This epidemiological study relied on self-report (SR) data because we wanted to collect information on a large sample and using PSG or, to a lesser extent, actigraphy would have increased the survey cost enormously, would have placed a greater inconvenience burden on participants, causing greater difficulty in recruiting the desired sample, and would have dramatically extended the length of an already lengthy study due to the limited availability of assessment instrumentation.

SR data have the advantages of:

• Being an inexpensive, convenient source of data.

• Not altering the normal sleep setting.

• Not altering normal sleep routines.

• Being the best available measure of subjective sleep perception.

We should acknowledge disadvantages of SR data that limit the information from this survey. Foremost, SR data do not inform us of sleep stages or the presence of occult sleep disorders, most notably sleep apnea or periodic limb movements. Also, the validity of SR data rests on the individual’s ability to recall and estimate sleep patterns, and this process necessarily introduces measurement error.

This epidemiological study was undertaken to gain knowledge about sleep that did not previously exist. Its primary goals are summarized next.

Establish Sleep Norms

Most of what we know about normal sleep derives from small-n PSG studies. In the prototypical study conducted by Williams, Karacan, and Hursch (1974), PSG data were collected from about 10 boys and 10 girls in 3- to 4-year age segments of childhood beginning with age 3–5 years and concluding with age 16–19 years. Thereafter, about 10 men and 10 women were similarly evaluated in each age decade through decade 70–79. Although this was a landmark study and was a significant advance in knowledge of how people of different ages normally sleep, its findings were based on the sleep of few individuals under artificial circumstances. Other methodological faults of this study can be noted. The mechanism by which participants entered this study was unspecified, but it did not appear to be a random survey, limiting its generalizability. Presumably, all participants were Caucasian (CA) because there was no mention of ethnicity.

The present study surveyed a large sample of participants, used random selection methods, and collected 14 nights of SR sleep data. Most previous epidemiological surveys of sleep have focused on insomnia and other aspects of abnormal sleep. By using sleep diaries, this survey obtained the largest body of data on normal sleep ever collected.

Illuminate Age, Gender, and Ethnic Differences

There have been epidemiological surveys that compared sleep among different age groups. There have been surveys that compared sleep of men and women. There have been surveys, although few in number, that compared the sleep of different ethnic groups. This is the first survey to comprehensively explore sleep across the full adult age span, gender, and ethnicity.

Acquire Detailed Information About Insomnia

Most epidemiological studies of insomnia have asked little more than, “Do you have insomnia, yes or no?” (see chap. 2). Some inquired about insomnia characteristics such as time to fall asleep and time awake during the night. The present study went well beyond this standard by collecting 2 weeks of sleep diaries. These data provide detailed description of the quantitative characteristics of the insomnia and the type of insomnia. For example, chapters 5 and 6 report on the prevalence of four types of insomnia: onset, maintenance, mixed, and combined, and how these are distributed across age, gender, and ethnicity.

Identify Daytime Correlates of Sleep

Participants completed seven questionnaires on their daytime functioning. Combining this set of data with the detailed information we collected on normal and disturbed sleep, we will be in a unique position to relate multiple aspects of sleep and daytime functioning, both within and between normal sleeping and insomnia groups. Again, these analyses will be age, gender, and ethnicity sensitive.

DISTINCTIVE METHODOLOGICAL FEATURES OF THE PRESENT EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SURVEY

The extant literature contains scores of epidemiological studies of sleep, and their methodology and findings are reviewed in chapter 2. The current epidemiological study boasts a distinctive set of methodological features, creating a rich compilation of information and elevating the confidence due our findings. Most of these methods separately appear in other studies, but this set of methods appears in no other single study.

Age and Gender Dependent Sampling

Random sampling is, of course, the hallmark of an adequate epidemiological study. However, because subpopulations are unevenly distributed, random sampling guarantees underrepresentation of some segments of the population. Thus, random sampling is likely to produce insufficient numbers of some subpopulations to permit reliable statistical analyses of these groups. Similarly, reliance on unfocused random sampling to collect cases to the criterion n ensures that some segments of the population will be oversampled. This does not compromise the statistical analyses, as does undersampling, but it is inefficient and costly.

We determined our stratified sampling needs at the outset of the study. Specifically, we estimated that if we obtained at least 50 men and 50 women from each age decade beginning with ages 20–29 and ending with the decade beginning with age 80 (no upper limit was placed on this last decade), we would have sufficient diversity and balance in gender and age to adequately analyze their association with sleep. We randomly sampled without restriction until a cell (defined as men or women within each of seven decades) was filled, and then it was closed to further sampling. Sampling continued until all 14 cells were closed.

The population of the Memphis area is equally divided between African Americans (AA) and CA, so we correctly assumed ethnicity would not have to be managed in order to obtain sufficient numbers of both groups. Our final sample permits us to study sleep across the adult life span, across gender, and across ethnicity. No other epidemiological study of sleep can conduct such analyses.

Prospective

Nearly all epidemiological studies have relied on retrospective accounts. In the prototypical study, data are collected from an interview or a questionnaire in which the participant is asked if he or she has insomnia, how long has it occurred, and so on. Before proceeding, some clarification on terminology is needed. When an individual is asked to report on his or her experience, all data are retrospective. The time frame distinguishes retrospective and prospective data. The former typically asks for an estimate covering a longer, more distant period of time, as in “How long did it typically take you to fall asleep over the past month?” compared to the latter, “How long did it take you to fall asleep last night?” Prospective data maximizes the immediacy of retrospective data. [Note that although the term prospective usually refers to a future event, we are using it to refer to the night just completed.]

A substantial basic and applied experimental literature on retrospective compared to prospective methodology usually shows both decreased accuracy and systematic bias associated with the former. Emotionally laden experiences weigh more heavily on recall than routine events, and momentary state at the time of recall colors the retrospective account. The preponderance of data demonstrates that retrospective accounts of clinical phenomena tend to exaggerate pathology (see reviews by Gorin & Stone, 2001; Korotitsch & Nelson-Gray, 1999; Mathews, 1997). Prospective data collection fares better than retrospective with respect to both accuracy and prejudice. When individuals report on their experience from this day forward, errors due to memory fault and bias due to one’s accumulated, global dissatisfaction are minimized.

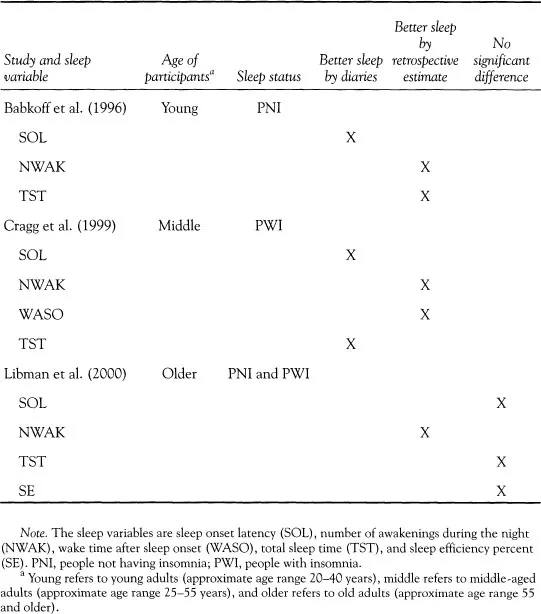

Three studies have actually compared retrospective point estimates of sleep to prospective sleep diaries (Babkoff, Weller, & Lavidor, 1996; Cragg et al., 1999; Libman, Fichten, Bailes, & Amsel, 2000). Despite the lessons of research from other domains and well-established theory, the results of these three investigations are equivocal (see Table 1.1). To summarize observed patterns, better sleep was reported on sleep diaries in three comparisons (mainly sleep onset latency), better sleep was reported on retrospective estimates five times (mainly number of awakenings during the night), and no significant differences were found three times.

The expectation of a strong bias toward reporting worse sleep on retrospective estimates was not supported. However, we do not believe this question is resolved. This small set of studies prevents adequate analyses of the influence of age, gender, emotional distress, and insomnia status on these two modes of sleep reporting. As already discussed, cognitive theory most strongly predicts that people with insomnia (PWI) would unintentionally bias their memory to recall exaggerated sleep deficits, and the weight of these three studies is not sufficient to dismiss the concern that retrospective reports serve to elaborate individuals’ negativistic thinking.

Multiple Sampling Points

The matter of prospective data and multiple sampling points are intertwined. Prospective data collection permits multiple sampling points. In the present study, sleep is sampled for 14 nights to yield a mean sleep parameter. Obtaining retrospective sleep data from an interview or a questionnaire, as in most prior epidemiological studies, restricts data collection to a single sampling point.

Reliability profits from averaging across multiple measurement points compared with single-point estimates. The overriding strongest influence in this matter derives from one of the most venerable of statistical concepts, the central limit theorem (Hays, 1963). The larger is the number of sampled values, the more closely their averaged value approximates the population mean and the smaller is the error associated with the estimate. The average of 14 sleep values is a more reliable measure of a person’s characteristic sleep than any one of those measures or any one summary retrospective estimate.

TABLE 1.1

Comparison of Retrospective Estimates of Sleep and Sleep Diaries

Single estimates are more vulnerable to one’s psychological state, be it uncharacteristically gloomy or cheerful, at the moment of estimation. Deviant experiences, as in a recent, unusually bad night of insomnia, may exert disproportionate influence on point estimates. In contrast, averaging across multiple sampling points smoothes out occasional deviant occurrences and is more likely to fairly represent typical experience. Recent research suggests that 14 sampling points, that is, 2 weeks, of SR home sleep data are needed to establish stable sleep estimates for most sleep measures (Wohlgemuth, Edinger, Fins, & Sullivan, 1999). Only two other epidemiological studies of sleep collected prospective sleep data, that is, sleep diaries (Gislason, Reynisdottir, Kristbjarnarson, Benediktsdottir, 1993; Janson et al., 1995). They both sampled within a restricted age range, and they both were limited to 1 week.

Comprehensive Evaluation of Daytime Functioning

Sleep cannot be well understood when insulated from the context of one’s diurnal experience. The affairs of one’s life, as in the presence of equanimity, distribution of exercise, and quality of diet, impact sleep, and our sleep experience reciprocates to help regulate daytime functioning. Profitable insight into the association between aging, gender, and ethnicity with sleep cannot proceed without knowledge of daytime experience. With equal certainty, knowledge of insomnia can advance little without relating disturbed sleep to the 24-hour experience.

The present epidemiological survey combines the most comprehensive evaluation of sleep with the most comprehensive evaluation of daytime functioning. The combination will hopefully yield a better understanding of both than has heretofore been possible.

SUMMARY CONCLUSIONS

This survey sets a new standard for the epidemiological study of sleep. We conducted a prospective, stratified, randomized epidemiological study of slee...