![]()

CHAPTER 1

Taking a Living Systems Perspective

WE NEED A NEW APPROACH to addressing the challenges of sustainability, which can be characterised as the failure of humans and the social systems they create to recognise they are part of the larger ecological system. As we get closer to ecological tipping points the challenge is one of human choice.

This chapter shows why we need to choose a living systems perspective, which means:

- Seeking the whole system view which recognises ourselves and our society are nested within our environment;

- Taking a relationship-based approach to cultivating change; and

- Learning and innovating towards a sustainable future.

Systems thinking

We are living in a world of ever-growing complexity. The whole of humanity on Earth is becoming more noticeably interdependent. Global communications, international governance, markets and supply chains make us increasingly interconnected. We are also faced with mounting dilemmas of sustainability, as inequality grows and we push up against our environmental limits and thus risk destroying our life support systems. This has never been as acutely demonstrated as through the effects of climate change where the challenge is truly global and affects us all, rich and poor. It can seem at times that we are locked into this trajectory. As a society we are putting more and more energy into repeating the same behaviours. We are struggling to find strategies and solutions to match the challenge.

Question: What strategies and approaches are you frustrated by that do not seem to address the urgency and scale of the challenge?

‘The world is a complex, interconnected finite, ecological-social-psychological-economic system. We treat it as if it were not, as it were divisible, separable, simple and infinite. Our persistent, intractable, global problems arise directly from this mismatch.’1

Systems thinking is one approach that might help us shift our perspective when trying to address the challenges of sustainability.A system is‘. . . a set of things – people, cells, molecules or whatever -interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behaviour over time’.2

Systems thinking focuses our attention not on the parts of the system but on how the parts work and operate together through their interconnectivity and relationships.

The kind of systems thinking that I find most useful draws on complexity theory and living systems analysis.3 This living systems perspective appreciates there is a deep structure of reality, or a pattern that connects all living creatures to the planet. The pattern that connects is that we are alive.

Living systems: Lessons from ecology

We can understand living systems through these three qualities4 -nested whole systems, resilience and self-organisation.

Nested whole systems

Living systems are embedded or nested within each other. Take your body for example: your stomach and digestive system are systems nested within your body. Our social system is embedded in our ecology. The retail sector is nested within our economy, the food system within our society as a whole.

‘Life started with single-cell bacteria, not with elephants.’5

This quality is what we ‘see’ when we look at a system. Most of the time when we ‘see’ a system it is dynamically stable. There are times however where new systems emerge. This evolution happens from the bottom up and when it does the emergent result is a new whole system. In nature you do not see systems that are partial – for example, a ‘nearly eye’ or ‘almost heart’.

To ensure systems are functioning optimally we need to understand that the larger layers serve the purpose of the nested sub-systems. For example, our body serves to support its cells. If this malfunctions, such as when cells break free and multiply exponentially causing cancer, the wider system (or our body in this case) malfunctions.

Recognising the nested nature of systems and paying attention to their alignment enables them to flourish.

Question: Think of a challenge you are trying to address at the moment. What happens when you step back and consider it within a wider system? Can you map the pattern?

Resilience and the importance of relationships

Although our systems seem stable, on closer inspection they are in constant flow. Using the example of our bodies again blood and nerve signals are constantly flowing. There are multiple feedback loops, relationships and interconnections that maintain its current state. When we cut our skin the blood causes a clot and works to restore and rebuild. Living systems may be stable but they are far from equilibrium.6

You characterise these relationships as a system’s resilience.

How resilient a system is depends on the multiplicity, diversity and variability of the relationships. The more of these a system has, the more resilient it is to shocks and changes. There are limits to this resilience. When it reaches these limits a system will tip or shift from one dynamic state to another. This shift means existing connections move around and reconnect in new ways. It becomes a radically different system from what existed before, as when fish stocks disappear or after the fall of the Roman Empire.

Question: What examples of a system tipping can you think of? What are the stable systems you rely on and what would happen if they tipped?

Self-organisation and learning at the heart of human life

If systems are dynamic, up until the point when they shift or a new system emerges, what drives them?

There is no evidence that there is an evolutionary plan; and yet we continually regenerate and evolve. This process is called self-organisation. Self-organisation is guided by a simple principle – life’s inherent tendency to create novelty.7

Humans create novelty through processes of innovation and learning. We are constantly trying out new ideas and actions, deliberately or not, some creating better results than others, so that we learn, adapt and evolve.

Question: Through history what innovations have driven wider change? What are some of the positive and negative impacts?

Sustainability: A systemic challenge

By exploring sustainability through the three qualities of a living system we can see why it is a living systems challenge and therefore why its perspective could be useful when seeking to cultivate a sustainable future.

Society nested in nature

‘Man talks of a battle with nature, forgetting that if he won that battle he would find himself on the losing side’

ECONOMIST FRITZ SCHUMACHER

The challenge of sustainability is often characterised as the failure of humans and the social systems we create (such as the economy) to recognise they are sub-systems of the larger ecological system. As we pursue goals of growth in our socio-economic sub-systems, which requires a constant throughput of environmental resources, we are starting to overshoot the carrying capacity of the environment. This will ultimately mean our ecological support system will malfunction.

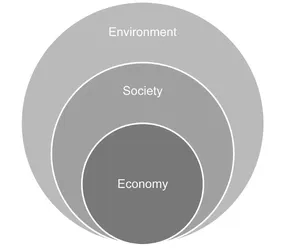

We need, therefore, to take a nested whole system perspective. Standard models of sustainability such as the three pillars of sustainability or the three overlapping circles of social, environment and economy are inadequate as they do not speak of the need to work within the ecological system and its limits. Instead, this can be represented in the nested diagram of the economy, nested within the social world, nested within the environment.

Question: What examples are there of socio-economic sub-systems not working within environmental limits?

Our reduced resilience can lead to tipping points

‘The organisation that destroys its environment destroys itself’

EARLY SYSTEMS THEORIST GREGORY BATESON

Our world (and therefore our existence) is maintained by the multitude of relationships that keeps it dynamically stable and resilient to changes. We rely on our ecological life support system to maintain certain functions so that we can live and survive on this planet: clean water, fertile soil and a stable climate.

Many writers, commentators and scientists are stating this resilience is being eroded. In our atmospheric system, for example, we are moving closer and closer to the point where it will be disrupted in an irreversible fashion. We are getting closer to the tipping point.

‘Non-linear systems are riddled with tipping points, but often a system is so complex that it is impossible to know exactly when these will be encountered.’8

We do not know when the thresholds of our ecological system might suddenly shift. For climate change it is suggested that 2 degrees Celsius might be the global limit of overall temperature rise beyond which we will witness irreversible change. Others say we have already reached that point in relation to carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Wherever we stand on this, we still need to change our path, take a living systems perspective and increase our resilience.

Question: How close do you believe we are to a critical tipping point? Do you think we can change the path we are currently on?

Can we learn our way out?

‘Climate change cannot be tackled ...