![]()

1

Titration in Trauma Work

Using the Play Therapist’s Palette

This project evolved as a response to repeated requests from clinicians who are familiar with the Flexibly Sequential Play Therapy (FSPT) trauma model, outlined in Play Therapy with Traumatized Children (Goodyear-Brown, 2010), to more fully explore the nuance of how we help children move toward and away from trauma content to create the story of what happened. The overarching goal of the work is to leach the emotional toxicity out of the child’s experience so that it can be integrated into a healthy sense of self. This model, formerly known as FSPT, has been renamed TraumaPlay™ in order to give more clarity to clinicians and clients alike. TraumaPlay™ is components-based and allows for a variety of interventions to be placed along a continuum of treatment, depending on which treatment goal is actively being addressed. Goals in the early phases of treatment include building safety and security, addressing and augmenting coping, soothing the physiology, enhancing emotional literacy, and helping parents be better partners in regulation while offering additional caregiver support to help them hold the hard stories of the children in their care. The middle phases of treatment provide some form of play-based gradual exposure that may include the continuum of disclosure, experiential mastery play, and/or trauma narrative work. The final phase of treatment is helping the child and family make positive meaning of the post trauma self.

When to invite children to go deeper, when to respect their defenses, when to acknowledge their retreat, when to celebrate that they have come to the end of what they can approach right now, and how to support their exposure work are questions with which both beginning and seasoned clinicians wrestle. An attuned trauma therapist is deciding, sometimes on a moment-to-moment basis, when to invite children out of stuck places, when and how much to push up against avoidance symptoms, when to witness their posttraumatic play (Gil, 2017), and when to support the need to simply rest. This volume is meant to expand significantly on the nuance of these questions while offering a new tool for thinking about the mitigators of a client’s approach to hard things.

If you work with traumatized children regularly, my guess is that you have already found yourself in a playroom environment with a child where you have been unsure when to offer invitations to further explore the traumatic event and when to allow the play to do its own healing work. As I train people both here and abroad, the struggle I hear clinicians wrestling with revolves around the question of when, how often, and how directly do I invite children to explore the trauma content in order to bring more coherence and when do I create a space of respite, mindfulness, and the simple and powerfully healing enjoyment of play? If we neglect the avoidance symptoms of posttraumatic reactions, we inadvertently collude with the trauma itself, communicating to the child that it is indeed too big and scary to be approached. If we push a child too hard or too fast, we can cause iatrogenic effects, flood them with anxiety, and shut down their healing process.

Another way this question gets put to me in training sessions is, when do you lead and when do you follow? The question is critically important and always excites me because the clinician asking is wanting to follow the child’s need rather than becoming dogmatic about either following the child’s lead or directing the therapeutic interactions in the room. A third way this question is asked is as follows: when does the therapist invite the child/family into new kinds of interaction and when does the therapist wait to be invited? Moreover, how do we extend moments of therapeutic work or help open and close circles of communication? Sometimes this question is not specific to the traumatic event but may be asked in relation to other goals of treatment, ones that would be considered symptomatic of the trauma itself, such as self-regulation abilities, hyperarousal symptoms, and a child’s ability to connect with others.

My response to this question of when to lead and when to follow, when to be more or less directive, is unpopular in our current protocolized culture: it depends. Beginning clinicians really do not like this answer, as the clearly defined steps of a protocol are soothing to them. As we grow, we become more comfortable with ambiguity and with trusting the process, but it remains important, even for seasoned clinicians, to ask this same question of when to lead and when to follow in a present-minded way in each and every session. One of my goals in supervision is to help clinicians become more comfortable with not having a definitive answer for what is needed per protocol so they can hone their ability to follow the child’s need from moment to moment. My goal is to help clinicians nurture the nuance in trauma work with children and families.

Nurturing the Nuance

Nuance is necessary—arguably in all forms of therapy and most certainly when using play therapy—with traumatized children and families. I have learned this lesson by going too slowly with a client system—not offering enough invitation to change or not providing enough strengthening of the muscles that hold hard things. I have also failed in the opposite extreme by attempting to take a child too quickly toward hard things. My concern about treatment becoming “cookie cutter-ish” applies to my model as much as to any other model of treatment. The flow of the treatment goals codified in TraumaPlay™ is pictured in Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Flowchart of TraumaPlay™, Formerly Known as FSPT

As clinicians have used the model, they have brought back questions and insights that have informed this deeper delineation of factors that I am offering here. As clinicians move through the components of TraumaPlay™, each individual goal of the model requires a nuanced titration of the clinician’s therapeutic self to see positive movement in the system. What we have found over and over again in supervision is that nuance is necessary every step of the way. In other words, the questions of “how much?” and “in what dose?” become constant reflections, helping clinicians hone this approach in ways that meet the individual needs of the client in front of them. Along the way, we are constantly aware of the titration of many aspects of engagement with the child and/or caregivers. The first goal of the model, establishing safety and security, may take minutes or months depending on the unique dynamics of the case and the interaction of these with the unique dynamics of the therapist’s presence and play space.

A continuum of directiveness exists within the field of play therapy, and the consensus is growing that there are times when a nondirective approach may be most beneficial and other times when a directive approach may lead to greater therapeutic growth. It is an exciting time in the field of play therapy. Several forms of play therapy have just been added to the SAMHSA list of evidence-based treatments. These include child-centered play therapy, filial therapy, and CPRT (all less directive in nature) and Theraplay and Adlerian play therapy (both more directive in nature).

With the addition of certain forms of play therapy to various evidence-based treatment lists, play therapy is becoming more recognized and respected in the larger therapy world. Although more research is needed in the area of play therapy, a vast amount of experimental research exists that proves the efficacy of many different forms of this therapy. Many of these studies were essential in the attainment of evidence-based therapy status. For example, numerous studies spanning over seven decades show the efficacy of using CCPT for children with various presenting problems and of differing ages (Bratton et al., 2013; Cochran, Nordling, & Cochran, 2010). Additionally, several meta-analyses show the general effectiveness of various types of play therapy interventions for children and adolescents (Bratton, Ray, Rhine, & Jones, 2005; Bratton & Ray, 2000; Leblanc & Ritchie, 2001). Beyond showing the effectiveness of play therapy, many studies also proved the effectiveness of additional clinical factors that most play therapists intrinsically incorporate into their practice. These additional factors, length of treatment and parental involvement, also impact the effectiveness of play therapy. Though research does show that play therapy is effective in short-term instances, it also demonstrates that the effectiveness of play therapy increases with the number of sessions provided. Numerous studies also show that when a parent is fully immersed in therapy and has ample opportunity to practice new skills, the chances for therapeutic success are increased (Bratton et al., 2005).

Unlike studies performed on adult populations, which usually exhibit similar results, play therapy research provisionally shows that some forms of play therapy are more effective with certain populations than others (Bratton et al., 2005). As mentioned in this chapter, play therapy exists on a continuum, and at times a client needs both directive and nondirective approaches in the same session. This recent research adds even more importance to the clinical task of assessing our client’s needs and responding in an effective manner.

Core Agents of Change in Play Therapy

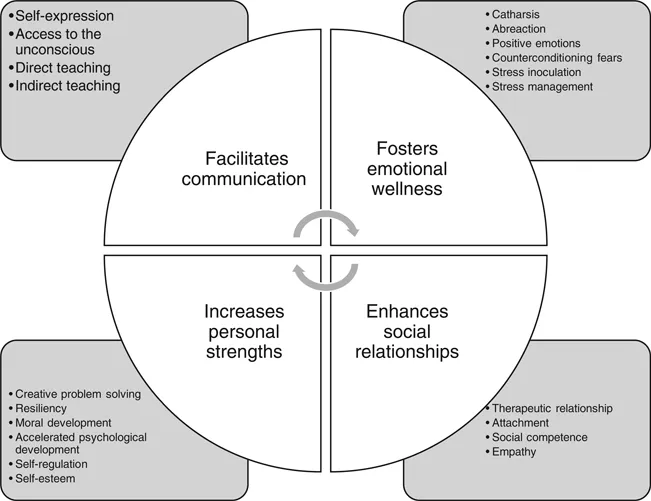

Those of you who are familiar with Charlie Schaefer’s The Therapeutic Powers of Play (Schaefer & Drewes, 2014) will embrace the idea that play provides therapeutic value of its own, that play can be the bridge to attachment enhancement, and that play can lead to increased solutioning abilities, foster useful exploration of roles (that may later be embraced or discarded) through a judgment-free role play environment, etc. These therapeutic powers of play are referenced here and broken down into broader categories of therapeutic goals (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 A Graphic Representation of the 20 Core Therapeutic Powers of Play

If you are new to play therapy as an overarching approach, it is worth familiarizing yourself with these, as these “powers” are foundational to the process, and only in a play therapy environment where these powers have been given freedom to work can clinicians begin to ask themselves these questions of nuance. Charlie has quoted Gordon Paul’s question to me many times over the years: “What treatment, by whom, is most effective for this individual with that specific problem, under which set of circumstances, and how does it come about?” (Paul, 1967, p. 111). Gordon Paul talked about the set of change mechanisms as “active ingredients,” and Schaefer and Drewes (2014) talk about them as “core change agents.”

Developing a treatment plan for a traumatized child requires us to identify the areas in which a child’s window of tolerance for the stress involved in basic life tasks has been compromised. In which area is the child’s window of tolerance most compromised? Is the child’s window of tolerance for acknowledging or holding big feelings the most compromised? Is the child’s window of tolerance for imperfection or mess the most compromised? Is the child’s ability to tolerate unknowns compromised? If so, which approach will help to expand the child’s window of tolerance in a baby-stepping way that does not create iatrogenic effects by tripping the child’s neurophysiology abruptly into hyperarousal or hypoarousal/collapse? This set of concerns is always in the background as I am working with a family. Once I have chosen the approach that I think is most helpful in this moment of work, I then move to my mitigators. I have found that these mitigators protect therapists—particularly new clinicians—from holding too tightly to a dogmatic implementation of the TraumaPlay™ model, or any other model, for that matter. The mantra at Nurture House is to prepare for a session thoroughly, have a plan going into the session, and then let it go and be in the present moment with the child or family. The whole array of potential mitigators is “tucked in their pocket” and gives them options for continuing to dance with the client when things get hard in session.

During the assessment phase of TraumaPlay™, clinicians are looking for clues about which aspects of growth-promoting interaction have been impeded by trauma. Clients feel uncomfortable or awkward when attempting these kinds of interactions. We call this the scary stuff for the child, the dyad, and/or the family system, and we begin targeting these growth areas long before we engage in trauma narrative work. I recently had a first session with parents in which the mother was unable to make direct eye contact with me at any point during our time together. This experience taught me that connection on this particular relational level was outside her window of tolerance; it was uncomfortable—even foreign—for her and was therefore, on some level, scary stuff. Which relational risks are uncomfortable for the traumatized child or family and which mitigators (named on the Play Therapist’s Palette, which will be explored later) of playful approach are most inherently attractive to that same child or family are two curiosities that are always held by clinicians during the assessment phase of TraumaPlay™.

Titration is a weird word. With its origins in hard science, the definition took me a while to absorb. But now that I have, I think it serves as a powerful way of framing the work we do with traumatized children and their families. Titration has to do with taking a beginning solution (a mixture of things) and adding bits of something else—sometimes called the change agent—in different amounts until you arrive at a new solution. A simplified version of titration happens when my children are making a Shirley Temple for a fancy event. They begin with a generous portion of ginger ale and then titrate the dose of grenadine by slowly adding drops of the bright red liquid until they have achieved the perfect sparkly, pinkish red color they are looking for. Add too much and you end up with a beverage that is too sweet to drink; add too little and it doesn’t seem very different from regular ginger ale. If the verb titrate refers to continually measuring and adjusting the balance of something, then I would suggest that play therapists are constantly engaged in titration whenever we are interacting therapeutically with a traumatized child and their caregivers.

For traumatized children, the beginning solution they bring to play therapy includes their unique set of experiences and resiliencies; their early relational ruptures, neglect, and maltreatment experiences; whatever traumas have occurred in their young lives and the way these may be manifested in their bodies by episodes of hyperarousal or hypoarousal; their beliefs about themselves; their “go to” emotions; and the ways they have learned to cope. Their beginning solution also includes their beliefs about how to navigate the world and how they negotiate getting their needs met in daily interactions. In order for change to occur, these children often need new experiences—doses of various aspects of therapeutic interaction—to help rewire the brain and body for healthier interactions with the world. In trauma work, the play therapist is the change agent: what we add and how much of it we add matters.

Although the concept of titration has long been understood and applied in the medical community—even among psychiatrists who work to titrate psychotropic medications to their most beneficial dose—there is little application of this term to behavioral health. The discussions that have occurred thus far seem to have more to do with optimal overall time frames for the implementation of treatment protocols—i.e., is 14 weeks enough time to see the change being hoped for, or is 18 weeks needed? The conversation can be much deeper than this. One benefit of the evidence-based practice (EBP) movement is that interventions have become more honed and targeted for specific populations; another is that therapists are being held to a higher level of accountability to be able to defend why they are doing what they are doing in therapy. With wide dissemination of this practice approach, adherence has become a constant topic for reflection, and literature abounds regarding fidelity to the protocol. Fidelity can be defined as “the degree to which a program is implemented following the program model, i.e. a set of well-defined procedures for such intervention” (da Silva, Fernandes, Lovisi, & Conover, 2014). Many of the new clinicians I help train come into this field already anxious about their performance—anxious about “getting therapy right”—and trainees may cling to a stepped protocol like it is a life vest.

The fidelity checklists...