eBook - ePub

Social Psychology

John D. DeLamater, Jessica L. Collett

This is a test

Share book

- 666 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Psychology

John D. DeLamater, Jessica L. Collett

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This fully revised and updated edition of Social Psychology is an engaging exploration of the question, "what makes us who we are?" presented in a new, streamlined fashion. Grounded in the latest research, Social Psychology explains the methods by which social psychologists investigate human behavior in a social context and the theoretical perspectives that ground the discipline.

Each chapter is designed to be a self-contained unit for ease of use in any classroom. This edition features new boxes providing research updates and "test yourself " opportunities, a focus on critical thinking skills, and an increased emphasis on diverse populations and their experiences.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Social Psychology an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Social Psychology by John D. DeLamater, Jessica L. Collett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Sociología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction to Social Psychology

Introduction

What Is Social Psychology?

A Formal Definition

Core Concerns of Social Psychology

Sociology, Psychology, or Both?

Theoretical Perspectives in Social Psychology

Symbolic Interactionism

Group Processes

Social Structure and Personality

Cognitive Perspectives

Evolutionary Theory

Five Complementary Perspectives

Summary

Critical Thinking Skill: An Introduction to Critical Thinking

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- Define social psychology and list the core concerns of the field.

- Understand five broad theoretical perspectives common in social psychology and describe the strengths and weaknesses of each.

- Comprehend the interdisciplinary nature of social psychology.

Introduction

Many of us are curious about the world around us. We ask ourselves questions, or pose them to friends, relatives, coworkers, or professors: What leads people to fall in and out of love? Why do people cooperate so easily in some situations but not in others? What effects do major life events like graduating from college, getting married, or losing a job have on physical or mental health? Where do stereotypes come from and why do they persist even in the face of contradictory evidence? Why do some people conform to norms and laws while others do not? What causes conflict between groups? Furthermore, why do some conflicts subside and others progress until there is no chance of reconciliation? Why do people present different images of themselves in various social situations, whether online or in person? Why are so many political and business leaders men? And why are they often paid more money than women when they work in the same positions? What causes harmful or aggressive behavior? What motivates helpful or altruistic behavior? Why are some people more persuasive and influential than others? Perhaps questions such as these have puzzled you, just as they have perplexed others through the ages. You might wonder about these issues simply because you want to better understand the social world around you. Or you might want answers for practical reasons, such as increasing your effectiveness in day-to-day relations with others.

Answers to questions such as these come from various sources. One such source is personal experience—things we learn from everyday interaction. Answers obtained by this means are often insightful, but they are usually limited in scope and generality, and they can also be misleading. Another source is informal knowledge or advice from others who describe their own experiences to us. Answers obtained by this means are sometimes reliable, sometimes not. A third source is the conclusions reached by philosophers, novelists, poets, and men and women of practical affairs who, over the centuries, have written about these issues. Often their answers have filtered down and become commonsense knowledge. We are told, for instance, that joint effort is an effective way to accomplish large jobs (“Many hands make light work”) and that bonds among family tend to be stronger than those among friends (“Blood is thicker than water”). These principles reflect certain truths and may sometimes provide guidelines for action.

Although commonsense knowledge may have merit, it also has drawbacks, not the least of which is that it often contradicts itself. For example, we hear that people who are similar will like one another (“Birds of a feather flock together”) but also that persons who are dissimilar will like each other (“Opposites attract”). We are told that groups are wiser and smarter than individuals (“Two heads are better than one”) but also that group work inevitably produces poor results (“Too many cooks spoil the broth”). Each of these contradictory statements may hold true under particular conditions, but without a clear statement of when they apply and when they do not, these sayings provide little insight into relations among people. They provide even less guidance in situations in which we must make decisions. For example, when facing a choice that entails risk, which guideline should we use—“Nothing ventured, nothing gained” or “Better safe than sorry”?

If sources such as personal experience and commonsense knowledge have only limited value, how are we to attain an understanding of social interactions and relations among people? One solution to this problem—the one pursued by social psychologists—is to obtain knowledge about social behavior by applying the methods of science. That is, by making systematic observations of behavior and formulating theories that are subject to testing, we can develop a valid and comprehensive understanding of human social relations. In this book we present some of social psychologists’ major findings from systematic research. In this chapter, we lay the foundation for this effort by introducing you to the field of social psychology and its major theoretical perspectives.

What is Social Psychology?

A Formal Definition

We define social psychology as the systematic study of the nature and causes of human social behavior. This definition has three main components. First, social psychology’s primary concern is human social behavior. This includes many things—individuals’ activities in the presence of others and in particular situations, the processes of social interaction between two or more persons, and the relationships among individuals and the groups to which they belong. Importantly, in this definition, behavior moves beyond action to also include affect (emotion) and cognition (thoughts). In other words, social psychologists are not only interested in what people do, but also what individuals feel and think (Fine, 1995).

Second, social psychologists are not satisfied to simply document the nature of social behavior; instead, they want to explore the causes of such behavior. This differentiates social psychology from a field like journalism. Journalists describe what people do. Social psychologists are not only interested in what people do but also want to understand why they do it. In social psychology, causal relations among variables are important building blocks of theory, and, in turn, theory is crucial for the prediction and control of social behavior.

Third, social psychologists study social behavior in a systematic fashion. Social psychology is a social science that employs the scientific method and relies on formal research methodologies, including surveys, diary research, experiments, observational research, and archival research or content analysis. These research methods are described in detail in Chapter 2.

Core Concerns of Social Psychology

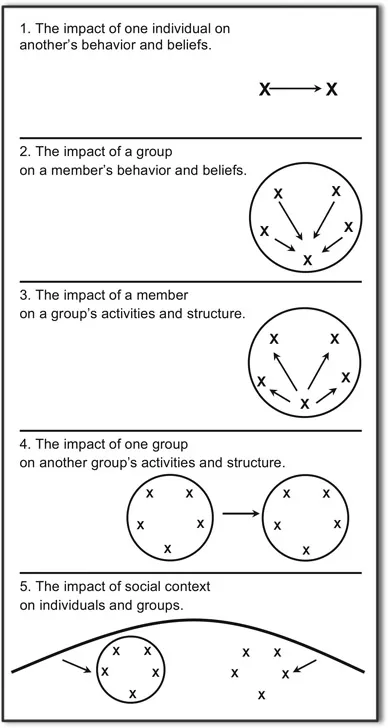

Another way to answer the question “What is social psychology?” is to describe the topics that social psychologists actually study. Social psychologists investigate human behavior, of course, but their primary concern is human behavior in a social context. There are five core concerns, or major themes, within social psychology: (1) the impact that one individual has on another; (2) the impact that a group has on its individual members; (3) the impact that individual members have on the groups to which they belong; (4) the impact that one group has on another group; (5) the impact of social context and social structure on groups and individuals. The five core concerns are shown schematically in Figure 1.1.

Impact of Individuals on Individuals. Individuals are affected by others in many ways. In everyday life, interactions with others may significantly influence a person’s understanding of the social world. Much of this happens simply by observation. Through listening to others and watching them, an individual learns how they should act, what they should think, and how they should feel.

Box 1.1 Test Yourself: Is Social Psychology Simply Common Sense?

Because social psychologists are interested in a wide range of phenomena from our everyday lives, students sometimes claim that social psychology is common sense. Is it? Five of the following commonsense statements are true. The other five are not. Can you tell the difference?

- T F When faced with natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes, people panic and social organization disintegrates.

- T F Physically attractive individuals are usually seen as less intelligent than physically unattractive individuals.

- T F The reason that people discriminate against minorities is prejudice; unprejudiced people don’t discriminate.

- T F People tend to overestimate the extent to which other people share their opinions, attitudes, and behavior.

- T F Rather than “opposites attract,” people are generally attracted to those similar to themselves.

- T F “Putting on a happy face” (i.e., smiling when you are really not happy) will not make you feel any different on the inside.

- T F People with few friends tend to live shorter, less healthy lives than people with lots of friends.

- T F The more certain a crime victim is about their account of events, the more accurate the report they provide to the police.

- T F If people tell a lie for a reward, they are more likely to come to believe the lie when given a small reward rather than a large reward.

- T F The more often we see something—even if we don’t like it at first—the more we grow to like it.

True: 4, 5, 7, 9 & 10.

Sometimes this influence is more direct. A person might persuade another to change their beliefs about the world and their attitudes toward persons, groups, or other objects. Suppose, for example, that Mia tries to persuade Andrew that all nuclear power plants are dangerous and undesirable and, therefore, should be closed. If successful, Mia’s persuasion attempt could change Andrew’s beliefs and perhaps affect his future actions (picketing nuclear power plants, advocating non-nuclear sources of power, and the like).

Beyond influence and persuasion, the actions of others often affect the outcomes individuals obtain in everyday life. A person caught in an emergency situation, for instance, may be helped by an altruistic bystander. In another situation, one person may be wounded by another’s aggressive acts. Social psychologists have investigated the nature and origins of both altruism and aggression as well as other interpersonal activity such as cooperation and competition.

Also relevant here are various interpersonal sentiments. One individual may develop strong attitudes toward another (liking, disliking, loving, hating) based on who the other is and what they do. Social psychologists investigate these issues to discover why individuals develop positive attitudes toward some people but negative attitudes toward others.

Figure 1.1 The Core Concerns of Social Psychology

Impact of Groups on Individuals. Social psychology is also interested in the influence groups have on the behavior of their individual members. Because people belong to many different groups—families, work groups, seminars, and clubs—they spend many hours each week interacting with group members. Groups influence and regulate the behavior of their members, typically by establishing norms or rules. Group influence often results in conformity, as group members adjust their behavior to bring it into line with group norms. For example, college fraternities and sororities have norms—some formal and some informal—that stipulate how members should dress, what meetings they should attend, whom they can date and whom they should avoid, and how they should behave at parties. As a result of these norms, members of particular groups behave quite similarly to one another.

Groups also exert substantial long-term influence on their members through socialization, a process through which individuals acquire the knowledge, values, and skills required of group members. Socialization processes are meant to ensure that group members will be adequately trained to play roles in the group and in the larger society. Although we are socialized to be members of discrete groups (sororities and fraternities, families, postal workers), we are also socialized to be members of social categories (woman, Latinx, working class, American). Outcomes of socialization vary, from language skills to political and religious beliefs to our conception of self.

Impact of Individuals on a Group. A third concern of social psychology is the impact of individuals on group processes and products. Just as any group influences the behavior of its members, these members, in turn, may influence the group itself. For instance, individuals contribute to group productivity and group decision making. Moreover, some members may provide leadership, performing functions such as planning, organizing, and controlling, necessary for successful group performance. Without effective leadership, coordination among members will falter and the group will drift or fail. Furthermore, individuals and minority coalitions often innovate change in group structure and procedures. Both leadership and innovation depend on individuals’ initiative, insight, and risk-taking ability.

Impact of Groups on Groups. Social psychologists also explore how one group might affect the activities and structure of another group. Relations between two groups may be friendly or hostile, cooperative or competitive. These relationships, which are based in part on members’ identities and may entail group stereotypes, can affect the structure and activities of each group. Of special interest is intergroup conflict, with its accompanying tension and hostility. Violence may flare up, for instance, between two families disputing land rights or between racial groups competing for scarce jobs. Conflicts of this type affect the interpersonal relations between groups and within each group. Social psychologists have long studied the emergence, persistence, and resolution of intergroup conflict.

Impact of Social Context on Individuals and Groups. Social psychologists realize that individuals’ behavior is profoundly shaped by the situations in which they find themselves. If you are listening to the radio in your car and your favorite song comes on, you might turn the volume up and sing along loudly. If you hear the same song at a dance club, you are less inclined to sing along but instead might head out to the dance floor. If your social psychology professor kicks off the first day of class by playing the song, chances are you won’t sing or dance. In fact, you might give your fellow students a quizzical look. Your love for the song has not changed, but the social situation shapes your role in the situation (club-goer, student) along with the expected behaviors based on that role. These contextual factors influence your reaction to the music.

These reactions are based, in part, on what you have learned through your interactions with others and through socialization in groups, the social influences discussed in the previous sections. However, as we grow and develop, the rules, belief systems, and categorical distinctions that have profound influence on our everyday lives seem to separate from these interactions. We forget that these things that feel or appear natural were actually socially constructed (Berger & Luck-mann, 1966).

Sociology, Psychology, or Both?

Social psychology bears a close relationship to several other fields, especially sociology and psychology.

Sociology is the scientific study of human society. It examines social institutions (family, religion, politics), stratification within society (class structure, race and ethnicity, gender roles), basic social processes (socialization, deviance, social control), and the structure of social units (groups, networks, formal organizations, bureaucracies).

In contrast, psychology is the scientific study of the individual and of individual behavior. Although this behavior may be social in character, it need not be. Psychology addresses such topics as human learning, perception, memory, intelligence, emotion, motivation, and personality.

Social psychology bridges sociology and psychology. In the mid-twentieth century, early in the history of social psychology, sociologists and psychologists worked closely together in departmen...