![]()

III.

Automated Essay Scorers

![]()

3

Project Essay Grade: PEG

Ellis Batten Page

Duke University

This chapter describes the evolution of Project Essay Grade (PEG), which was the first of the automated essay scorers. The purpose is to detail some of the history of automated essay grading, why it was impractical when first created, what reenergized development and research in automated essay scoring, how PEG works, and to report recent research involving PEG.

The development of PEG grew out of both practical and personal concerns. As a former high school English teacher, I knew one of the hindrances to more writing was that someone had to grade the papers. And if we know something from educational research it is that the more one writes, the better writer one becomes. At the postsecondary level where a faculty member may have 25 to 50 papers per writing assignment, the task of grading may be challenging, but manageable. However, in high school, where one writing assignment often results in 150 papers, the process is daunting. I remember many long weekends sifting through stacks of papers wishing for some help. The desire to do something about the problem resulted, seven years later, in the first prototype of PEG.

In 1964, I was invited to a meeting at Harvard, where leading computer researchers were analyzing English for a variety of applications (such as verbal reactions to a Rorschach test). Many of these experiments were fascinating. The meeting prompted me to specify some strategies in rudimentary FORTRAN and led to promising experiments.

EARLIEST EXPERIMENTS

The first funding to launch this inquiry came from the College Board. The College Board was manually grading hundreds of thousands of essays each year and was looking for ways to make the process more efficient After some promising trials, we received additional private and Federal support, and developed a program of focused research at the University of Connecticut.

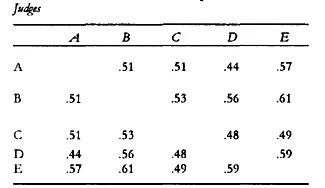

By 1966 we published two articles (Page 1966a, 1966b), one of which included the Table shown later (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.1 Which one is the Computer?

Most numbers in Table 3.1 are correlations between human judges, who independently graded a set of papers. Judges correlated with each other about .50. In the PEG Program, “Judge C” resembled the four teachers in their correlations with each other. In that sense, the experiment met Alan Turing’s famous criterion related to artificial intelligence that an outside observer could not tell the difference between performance on the computer and human performance.

Although Table 3.1 suggested that neither humans nor computers produced stellar results, it also led to the belief that computers had the potential to grade as reliably as their human counterparts (in this case, teachers of English).

Indeed, the mid-1960s were a remarkable time for new advances with computers, designing humanoid behavior formerly regarded as “impossible” for computers to accomplish. Thus, PEG was welcomed by some influential leaders in measurement, in computer science, schooling, and government, as one more possible step forward in such important simulations.

The research on PEG soon received federal funding and one grant allowed the research team to become familiar with “The General Inquirer,” a content analytic engine developed in the early 60s. A series of school-based studies that focused on both style and content (Ajay, Tillett, & Page, 1973; Page & Paulus, 1968) was also studied. PEG set up a multiple-classroom experiment of junior- and senior-high classes in four large subject-matter areas. The software graded both subject-knowledge and writing ability. Combining appropriate subject-matter vocabulary (and synonyms) with stylistic variables, it was found that PEG performed better by using such combinations than by using only one or the other. Those experiments, too, provided first-ever simulations of teacher content-grading in the schools.

Despite the early success of our research, many of our full-scale implementation barriers were of a practical nature. For example, data input for the computer was accomplished primarily through tape and 80-column IBM punched cards. At the time, mainframe computers were impressive in what they could do, but were relatively slow, processed primarily in batch mode, and were not very fault-tolerant to unanticipated errors. Most importantly, access to computers was restricted from the vast majority of students either because they did not have accounts or they were unwilling to learn the lingua franca of antiquated operating systems. The prospect for students to use computers in their own schools seemed pretty remote. Thus, PEG went into “sleep mode” during the 1970s and early 1980s because of these practical constraints and the interest of the government to move on to other projects. With the advent of microcomputers in the mid 1980s, a number of technology advances appeared on the horizon. It seemed more likely that students would eventually have reasonable access to computers, the storage mechanisms became more flexible (e.g., hard drives and floppy diskettes), and computer programming languages were created that were more adept at handling text rather than numbers. These developments prompted a re-examination of the potential for automated essay scoring.

During the “reawakening” period, a number of alternatives were formulated for the advanced analysis of English (Johnson & Zwick, 1990; Lauer & Asher, 1988; Wical & Mugele, 1993). Most of these incorporated an applied linguistics approach or attempted to develop theoretical frameworks for study of writing assessment. In the meantime, we turned our attention to the study of larger data sets including those from the 1988 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP).

These new student essays had been handwritten by a national sample of students, but were subsequently entered into the computer by NAEP typists (and NAEP’s designs had been influenced by PEG’s earlier work). In the NAEP data set, all students responded to the same “prompt” (topic assignment). For the purposes of this study, six human ratings were collected for each essay. Using these data, randomly-selected formative samples were generated which predicted well to cross-validation samples (with “r”s higher than .84). Even models developed for the one prompt predicted across different years, students, and judge panels, with an “r” hovering at about .83. Statistically, the PEG formulations for reliability now surpassed two judges which matched the typical number of human judges employed for most essay grading tasks.

BLIND TESTING—THE PRAXIS ESSAYS

Because of their emerging interest in the topic of automated essay scoring, the Educational Testing Service (ETS) commissioned a blind test of the Praxis essays using PEG. In this experiment, ETS provided 1,314 essays typed in by applicants for their Praxis test (the Praxis program is used in evaluating applicants for teacher certification). All essays had been rated by at least two ETS judges. Moreover, four additional ratings were supplied for 300 randomly-selected “formative” essays, and the same number of 300 “cross-validation” essays.

The main outcomes are shown in Table 3.2 (Page & Petersen, 1995). Table 3.2 presents the prediction of each separate judge with the computer (PRED column). Furthermore, the PEG program predicted human judgments well—better even than three human judges.

In practical terms, these findings were very encouraging for large-scale testing programs using automated essay scoring (AES). Suppose that 100,000 papers were to be rated, and PEG developed a scoring model based on a random sample of just 1,000 of them. Then, for the remaining 99,000 papers, computer ratings could be expected to be superior to the usual human ratings in a striking number of ways: