eBook - ePub

Excavations at Hulton Abbey, Staffordshire 1987-1994

- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Excavations at Hulton Abbey, Staffordshire 1987-1994

About this book

"Hulton Abbey was a minor Cistercian monastery in north Staffordshire (England), founded in 1219 and finally dissolved in 1538. This is the final report on the archaeological excavations undertaken there between 1987 and 1994. In particular, the chapter house was uncovered and re-assessed and the eastern part of the church and north aisle were completely excavated, together with the eastern half of the nave. The excavations are described by area and chronological phase with detailed specialist reports including architectural stonework and decorated floor tiles. An extensive programme of sampling and analysis of pollen remains from burials was also completed. The remains of 91 individuals, mainly men but also women and children, are reported on in detail, with sections on abnormalities and pathology as well as medieval burial goods such as a wax chalice and wooden wands. Comparisons with other published monastic sites in the region help to place Hulton into a wider context. An important element of the project was education and community involvement and today the site lies in a small urban park in Stoke-on-Trent."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Excavations at Hulton Abbey, Staffordshire 1987-1994 by William D. Klemperer,Neil Boothroyd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

1.1 The Cistercians

by W D Klemperer

In 1098 a group of malcontents led by a French monk, Robert de Molesme, broke away from the Cluniac dominated monastic world and founded an abbey at Citeaux in Burgundy, France. They established a more rigorous monastic lifestyle, claiming a return to the original ideals of St Benedict's Rule. Under its charismatic early leader St Bernard of Clairvaux (d 1153), and benefiting from a dynamic central control exercised from the mother house of Citeaux, the Cistercian order quickly expanded. In 1147 the Cistercians took over the smaller Savigniac order, which remained a distinctive element in the Cistercian family. This expansion was assisted by the popularity of the Cistercian 'back to basics' message, and leaders of medieval society sought to associate themselves with the order in order to gain spiritual benefit. Benefactions, often of land, fuelled rapid expansion in the 12th century throughout western Europe, based upon a new economic model in which the Cistercians retained direct control of their economy. Monastic farms or 'granges' were founded in order to control economic production and distribution, a system which relied on the recruitment of conversi or laybrothers who took religious vows but whose purpose was to act as a direct labour force. Remote locations were often chosen for foundations, where spiritual purity might be more easily attained, but also where new land could be taken into grazing for the vast flocks of sheep that came to characterise the English Cistercian economy. The order spread quickly and by 1153 there were 343 Cistercian abbeys throughout Europe, this number more than doubling to 738 Cistercian houses for men and 654 for women by 1500 (Lawrence 1984, 153). In Britain the first Cistercian house was established at Waverley (Surrey) in 1128 and by 1154 there were 53 Cistercian abbeys in England and Wales (although 13 of these had originally been founded as Savigniac houses), as well as 11 nunneries following Cistercian rules but not yet officially recognised as Cistercian (Knowles 1940).

The order maintained strict rules according to the terms of the Carta Cariiatis which was read at all meetings of the Chapter General, an annual meeting of Cistercian abbots, normally held at Citeaux on the Vigil of the Holy Cross on 13 September. Although abbots from far away places such as Syria attended less frequently, the meetings expanded rapidly and became a principal method of retaining a distinctively Cistercian identity throughout western Europe. This identity was also protected through a system of filiation whereby every new foundation was established from a mother house. The abbot of the mother house would carry out an annual visitation of all the daughter houses to ensure uniformity of observance. In turn daughter houses could become mother houses to a new generation of foundations.

As the order expanded so did its wealth. In a world that believed literally in heaven, hell and purgatory, it was vital to gain spiritual benefit during the transient time on earth. The object was a place in heaven, or at least to gain remission from purgatory and the eventual assurance of a place in heaven. The saying of mass for the benefit of a person's soul was especially important in this regard. The numerous benefactions the order gained in return enabled a significant portion of the lucrative wool trade to be cornered. Depending on local opportunities numerous other industrial activities were developed such as metal and leather working and the mining of coal and lead. The burgeoning wealth of the Order was preserved by exemptions from taxes and in time the Order, perhaps inevitably, strayed away from the high ideals of its founders. The Cistercian rule was breaking down by the 13th century and an increasingly aggressive approach to business during the 14th and 15th centuries saw growing involvement with the commercial secular world. Land began to be purchased despite the Chapter General ruling against it and urban properties were bought and leased to lay people. The simple diet was increasingly abandoned as attested by numerous new meat kitchens, such as those at Jervaulx and Kirkstall (Moorhouse and Wrathmell 1987). The lay-brother system dwindled and failed during the 14th century due to a lack of recruits, especially after the plague of the 1340s and the consequent shortage of labour. To compound the lack of spiritual clarity, the Cistercians had also failed to adapt sufficiently to the emergence of towns and a socially mobile middle class. The preaching orders of friars had moved into the towns in the 13th century while the Cistercians remained remote. The Dissolution instigated by Henry VIII between 1534 and 1540 brought the Cistercian and wider monastic world to a close and was accompanied by large-scale destruction of monastic sites.

1.2 Monasticism in Staffordshire

by N Boothroyd

Wilfred, bishop of York, and Chad, first bishop of Lichfield, are credited with the foundation of monasteries in the Staffordshire area by the mid 7th century but little is known of these foundations. The first major monastic foundation was Burton Abbey, a Benedictine house founded in 1004 near the Derbyshire border. It soon acquired royal patrons and was the wealthiest monastery in Staffordshire throughout the medieval period, though never of national importance. Two other Benedictine houses were founded along the southern borders of the county in the 12th century, Canwell Priory c1140 and Sandwell Priory c1180, and two alien priories in the late 11th century at Lapley, also in the south, and Tutbury, on the Derbyshire border. Nuns were catered for by three Benedictine priories founded by Roger de Clinton, Bishop of Lichfield 1129-48, at Blithbury, Brewood, and Farewell, again all in the south of the county. An attempt to establish a Cistercian abbey at Radmore (or Red Moor) in the royal forest at Cannock in south Staffordshire lasted less than 10 years, the monks moving to Stoneleigh in Warwickshire in 1154.

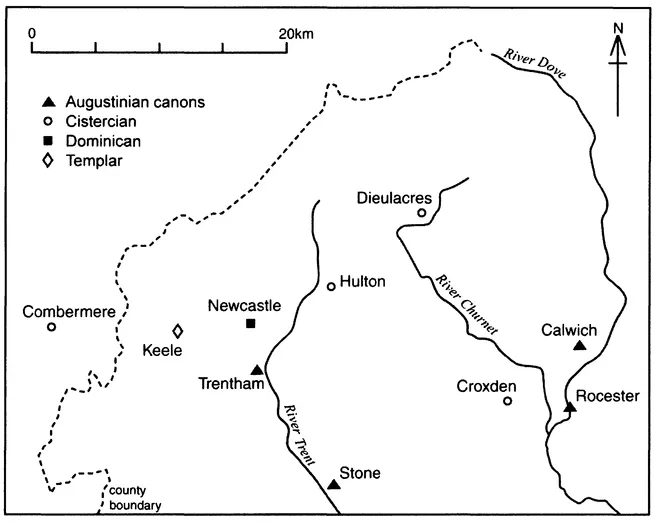

It was the Augustinians who undertook the monastic colonisation of north Staffordshire in the 12th century. Priories of Augustinian canons were established at Calwich (c1125-30), Stone (c1138-47), Ranton (c1160), Trentham (c1153), St Thomas near Stafford (1174), and an abbey at Rocester (c1141-46) (Greenslade 1970). The Augustinians were responsible not only for the establishment of religious houses but also for large scale landscape clearance at these sites; the foundation charter of Ranton priory in mid-Staffordshire, for example, describes the house as 'St Mary des Essarz', in other words, on assarted land (Studd 1986, n 7).

The Cistercians thus entered a crowded monastic landscape when the first abbey at Cotton was begun in 1176, moving a couple of kilometres to Croxden three years later. With the foundation of Dieulacres (moving from Poulton in Cheshire) in 1214 and Hulton in 1219 the Cistercians actually broke their own regulations concerning the placing of abbeys at a minimum of six leagues apart, approximately 23 to 35km, despite the protests of the abbot of Croxden (Tomkinson 1997). Of course, the extent to which any religious order could choose the sites of its monasteries, as they were reliant on the gift of lands from lay patrons, is an interesting question (see Burton 1986 for the relationship between patrons and Cistercian abbeys in the 12 th century).

Later religious foundations in the county were almost all of friars who established themselves in three Staffordshire towns in the 13th century: Franciscans and Augustinians in Stafford, Franciscans in Lichfield and, closest to Hulton and the only ones in the north of Staffordshire, Dominicans at Newcastle-under-Lyme some time before 1277 (Greenslade 1970). The Templars also established a preceptory at Keele some time between 1216 and 1255, on land they had acquired in the 1150s or 1160s (Studd 1986).

According to the Victoria County History for Staffordshire 'few of these monasteries had more than local significance, and some of them lacked even that' (Greenslade 1970, 135). All of them, though, are likely to have had a significant impact on their local economy and landscape. Even absentee landlords such as the Templars and later the Hospitallers, who took over Keele following the suppression of the Templars in 1308, influenced the type of cultivation on their estate, with large scale assarting in the 12th century and, because they gave such generous terms to their tenants at Keele, open field arable farming continued into the 15th century despite the high rainfall, high altitude and generally unfavourable conditions for arable there (Studd 1986).

1.3 The History of Hulton Abbey

by W D Klemperer

There were 82 permanent Cistercian foundations in Britain, of which 62 lay in England (Robinson 1998, 63). Of these, four were in Staffordshire. Radmore was founded c1143 (moving to Warwickshire in 1154), Croxden in 1179, Dieulacres in 1214 and finally Hulton in 1219. Hulton was therefore the last of the south Pennines-Cheshire plain group of Cistercian monasteries of Savigniac ancestry originating with Combermere (Cheshire) in 1133, Combermere's other daughter houses being Poulton (Cheshire) c1146-53 (moved to Dieulacres in 1214) and Stanlow (Cheshire) 1172 (moved to Whalley, Lancashire, in 1296). Croxden, another Savigniac house, was a daughter of Aunay-sur-Odon, Normandy. The Staffordshire houses all post-date the most vigorous period of Cistercian expansion in the first half of the 12th century, perhaps a reflection of the marginal and untamed nature of north Staffordshire in the Middle Ages (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1

Monastic houses in North Staffordshire

Monastic houses in North Staffordshire

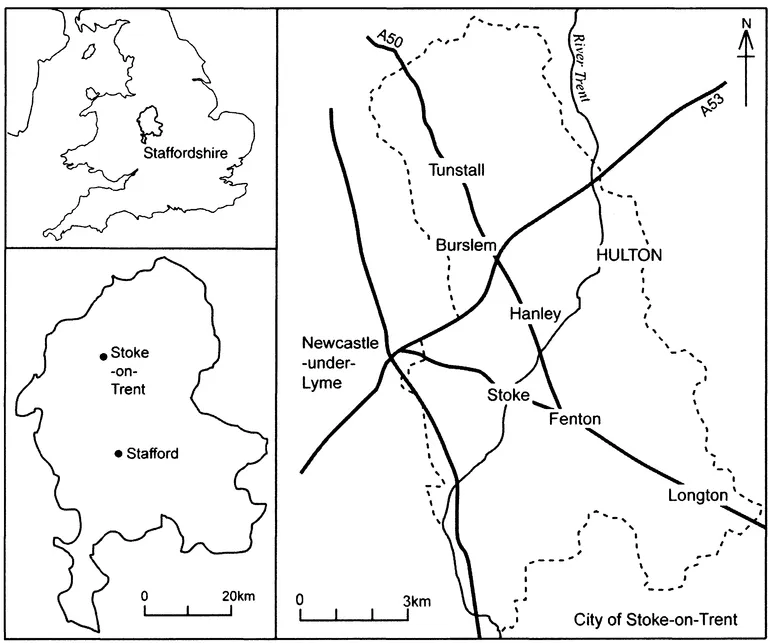

FIGURE 1.2

Location plan of Hulton Abbey

Location plan of Hulton Abbey

Of the north Staffordshire Cistercian houses Hulton was the poorest and little remains above the ground (Figure 1.2). The site in the modern-day suburb of Abbey Hulton in Stoke-on-Trent bears little resemblance today to the lonely upland valley to which the monks moved in 1219 (Figure 1.3).

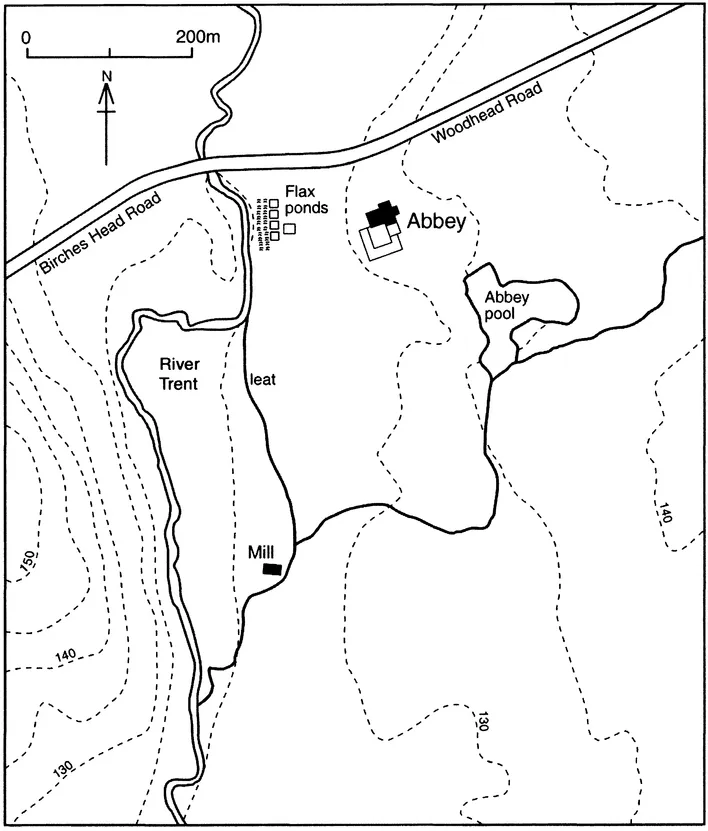

FIGURE 1.3

Hulton Abbey in its medieval topography. Birches Head Road may follow a medieval route

Hulton Abbey in its medieval topography. Birches Head Road may follow a medieval route

Documents related to Hulton have survived in the records of the Aston family after Sir Edward Aston purchased the site of the Abbey in 1542. Some of this material was eventually deposited in the William Salt Library in Stafford. Other documents survive in the British Museum, the County Record Office and at Keele University Library.

The founder of the abbey was Henry of Audley, a rising star of the area in the early 13th century. Henry was a vassal of Ranulph, Earl of Chester. Ranulph went on crusade in 1218, leaving Henry in charge of his territories. Henry founded Hulton soon afterwards, perhaps in lieu of not joining the crusade, or as thanks for his successful career. Monks from Combermere Abbey came to oversee the building and the first brothers were ordained on 25 or 26 July 1218 or 1219 (Janauscheck 1877, 223). Only a few Cistercian houses are later in date and, as such, Hulton represents the dying flickers of the great expansion of the preceding century. The late foundation, however, may also be interpreted as part of a late flowering with the benefit of royal patronage. King John, it might be argued, initiated this final flourish by founding Beaulieu (Hampshire) in 1203 and one of his leading supporters, Earl Ranulph of Chester, no doubt taking his lead from the king, then founded Dieulacres in 1214. When Henry of Audley, who was a vassal of Ranulph's, wished to found a monastery it was no surprise, therefore, that he looked towards the Cistercians. The foundation charter was granted in 1223 (Dugdale 1817-30) giving Staffordshire estates at Hulton and Rushton, and at nearby Normacot. An additional estate was added in 1232 at Mixon and Bradnop on the Staffordshire moorlands (British Library Cotton Ch Xi/38), and further Staffordshire grants were made by lesser landowners such as Henry de Verdon, who gave land at Bucknall (Parker 1909, 8), and Simon de Verney, who gave land at Normacot. In 1256 a royal charter was obtained recording the lands of the community and its main benefactors.

Despite unsettled periods, Hulton managed to establish a reasonably successful economy during the 13th century, largely based on sheep farming at its granges. By 1235 a home grange was in existence, as well ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- FOREWORD

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The excavations 1987–94

- 3 Structural evidence

- 4 The burials

- 5 Environmental evidence

- 6 Finds

- 7 Discussion

- Bibliography

- Index