CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

The message of this book is a simple one: children learn to draw by acquiring increasingly complex and effective drawing rules. In this respect learning to draw is like learning a language: children learn to speak, not just by adding to their vocabulary, but by learning increasingly complex and powerful language rules. And like learning a language, learning to draw is one of the major achievements of the human mind.

As with the early rules of speech, the drawing rules young children use are different from those used by adults. This is why drawings by young children look so strange. It follows that if we are to make sense of children’s drawings we have to establish what these rules are and understand how and why they change as children get older. My hope is that parents and teachers will gain more pleasure from children’s drawings if they understand these rules and, by understanding them, gain a clearer insight into what children are trying to do when they are learning to draw.

The account of children’s drawings given here is different from those generally available. I make no apology for this because although children’s drawings have now been studied for more than a century there is no generally accepted theory that can account for them, and existing theories are full of contradictions and confusions. The main reason for this is that all these theories have been derived, in one way or another, from theories of visual perception that now seem inadequate. As a result of new theories of perception developed during the 1970s and 1980s, it is now possible to see how we might begin to construct a new account of children’s drawings that can not only explain the many strange features in children’s drawings but also enable us to see how all the contradictions and confusions in previous theories have arisen.

In 1982 David Marr, working at MIT, published Vision, a book that revolutionized the study of visual perception. Although many of the details of his theory are still controversial, the broad outlines of his account of vision are now widely accepted. This new account of vision, which was set against the background of computing technology and information processing, was radically different from the optical theory of vision that had dominated theories of children’s drawings since the end of the 19th century. I shall call this earlier account the camera theory of perception.

According to the camera theory, we receive and store our perceptions of the world in the form of internal images that resemble the kinds of images we get by taking a photograph. This leads naturally to a theory of picture production in which internal images are copied on to the picture surface, very much as the image in a camera is copied on to a print. This traditional theory was summed up by the psychologist J. J. Gibson (1978):

Drawing is always copying. The copying of a perceptual image is drawing from life. The copying of a stored image is drawing from memory. The copying of an image constructed from other images is drawing from imagination. (p. 230)

Internal images of this kind are necessarily in perspective, and it is obvious that children’s drawings do not fit comfortably into this theory. Not only are young children’s drawings not in perspective, but they contain many other anomalies judged by the standards of photographic realism, including so-called transparencies and the lack of foreshortening. Explaining the presence of these features faced psychologists with a dilemma, which they attempted to solve in various ways. I describe some of their attempts in more detail in chapter 2, but by far the most common explanation was to say that although older children draw what they see, young children draw what they know. According to this account, very young children do indeed see the world in terms of perspectival mental images but by the time they begin to draw, this pure, innocent vision has become corrupted by knowledge, that is, by the concepts they form of objects and the expression of these concepts in language.

According to the copying theory ofdrawing, the anomalies in young children’s drawings are simply faults: either because children lack manual dexterity or because they draw their concepts of objects rather than their appearance. These anomalies appear in children’s drawings from the time they first begin to draw until the age of 7 or 8 years. At this point, by a developmental process that is never fully explained, children are somehow able to get back to the state of visual innocence that had previously been repressed by knowledge. Against the background of the camera theory of vision, and its corollary in the form of copying theories of picture production, some account of children’s drawings of this kind seemed unavoidable.

The problem with this account, however, is that it is not only very depressing in its mechanistic approach to picture making but it seems to run counter to our intuitions. There is a magic about children’s drawings that makes them much more exciting, imaginative, and entertaining than either true photographs or the optically realistic academic paintings that were being produced at the end of the 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century many art teachers, led by Franz Cizek in Austria and Marion Richardson in England, began to claim that the features in children’s drawings that developmental psychologists had dismissed as faults were precisely those features that contributed to their magic. They were able to do this because many of these features seemed remarkably similar to those that were appearing in paintings and drawings by avant-garde artists such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Paul Klee. Moreover, they were supported in this view by many of the artists themselves. Picasso claimed that it had taken him his whole lifetime to learn to draw like a young child, and Klee declared that “the pictures that my little boy Felix paints are often better than mine” (quoted in Wilson, 1992, p. 18). As Fineberg (1997) has shown a number of avant-garde artists including Klee made collections of children’s drawings and used motifs taken from them in their work.

Advocates of the new art teaching, as it came to be called, claimed that the magical quality of the drawings children produce showed that they had an innocence and purity of vision that the avant-garde artists had managed to retain, uncorrupted by bourgeois materialistic values and the outmoded conventions of Western academic painting. Thus, whereas the psychologists believed that the faults in the drawings that children produce up to the age of, say, 7 or 8 years are the result of their vision being spoiled by knowledge and language, the new art teachers believed that it was precisely these “faults” that demonstrated children’s creativity and their purity of vision. It followed from this that the primary job of art teachers was to protect children for as long as possible from the corrupting values of conventional society and, in particular, to avoid any kind of overt teaching so that the child’s creativity could develop naturally, “like a flower unfolding.”

These two accounts of children’s drawings are, of course, irreconcilable. From a theoretical point of view this is unsatisfactory, but the lack of any credible and generally accepted theory of children’s drawings has also had some unfortunate practical consequences. Psychologists have, perhaps rightly, not seen it as part of their job to give advice on teaching, and in any case if the change from intellectual to visual realism takes place inevitably as the result of maturation, teaching drawing is unnecessary. Within the standard psychological model the faults in children’s early drawings are something they just have to grow out of. The new art teachers, on the other hand, saw any kind of teaching as positively harmful, but a teaching method that relies on an avoidance of teaching is ultimately indefensible. As a result we have an adult population who say, almost universally and truthfully, that they cannot draw.

However, we now have an opportunity, not of reconciling these contradictory accounts of children’s drawings but of developing a new account that avoids most of these difficulties in the first place. This opportunity is provided by two recent developments, one in the field of visual perception and the other in the study of natural languages.

The old camera model has been replaced by a theory of vision in which internal representations of objects and scenes can take two possible forms. Marr (1982) called these viewer-centered and object-centered internal descriptions.1 Viewer-centered descriptions provide us with an account of objects and scenes as they appear from a particular point of view, so that one object can be described as behind another, and a description of the top of a table, for example, might take the form of a trapezium. Viewer-centered descriptions of this kind are not, perhaps, so very different from the perspectival mental images of the older camera model, and we need them because they tell us where things are in relation to ourselves.

However, we also need to be able to recognize objects, and it would be uneconomic and impractical to do so by storing images of objects as they appear from all possible points of view and under all possible lighting conditions. Instead, Marr (1982) proposed that we need to be able store internal representations of the shapes of objects in the form of object-centered descriptions: descriptions that are given independently of any particular point of view. In an object-centered description of a table, for example, the top of a table would take the form of rectangle, and the positions of objects or parts of objects on the table would be described relative to the principal axes of the table rather than to the position of the viewer. Marr argued that the primary function of the human visual system is to take the ever-changing viewer-centered descriptions available at the retina and use them compute permanent object- centered descriptions that can be stored in long-term memory. We then use these object-centered descriptions to recognize objects when we see them again from different directions of view or under new lighting conditions.

I shall show that most children’s drawings (even those that look optically realistic) are derived from object-centered internal descriptions rather than from views. It might seem that this is only the old “young children draw what they know” in a new and more sophisticated guise, but this is not the case. The reason for this is that because object-centered descriptions are given independently of any particular point of view they must be three- dimensional. Thus, in learning to draw, children have to discover ways of mapping these three-dimensional internal descriptions of objects on to a two-dimensional surface, and they do this by acquiring increasingly complex and effective drawing rules.

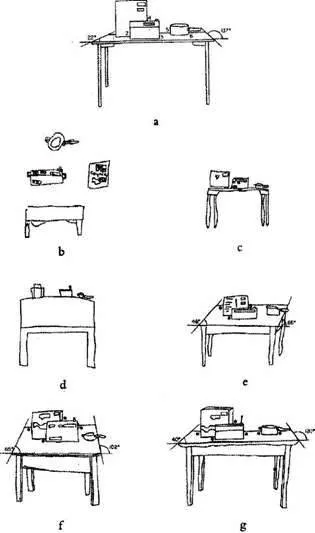

Figure 1.1 shows the results of an experiment in which children of various ages were asked to draw a table from a fixed viewpoint. In terms of the camera theory of drawing, these results are inexplicable because only drawings of the types shown at Fig. 1.1g, and perhaps Fig. 1.1f, could be derived directly from the child’s view of the table. They are, however, easy to explain if we say that these children were discovering increasingly complex and effective rules for mapping three-dimensional object-centered descriptions of the table onto the two-dimensional surface of the paper. In all these drawings horizontal lines in the picture are used to represent the horizontal edges of the table, and vertical lines in the picture are used to represent the vertical edges. But the problem these children were faced with was to find a way of representing edges in the third, front-to-back, direction. A few of the drawings were left unclassified because the spatial relations between the objects on the table and the table itself were incoherent (Fig. 1.1b). The rest of the drawings were classified in terms of the various projection systems (of which perspective is just one example), in which front-to-back relations in the scene are represented in different ways on the picture surface. In drawings of the type shown at Fig. 1.1c the front-to-back edges of the table were simply ignored. In drawings of the type shown at Fig. 1.1d the problem has been solved in a simple way: front- to-back edges in the scene are represented by up-and-down lines in the picture. But the problem with this solution is that one direction on the picture surface has been used to represent two different directions in three-dimensional space. As a result, drawings of this type tend to look flat and unrealistic. Nevertheless, drawings of this type were the most frequent of all the types of drawings produced in this experiment.

FIG. 1.1. Children’s drawings of a table, showing typical drawings in each class: (a) the view the children were asked to draw; (b) Class 1, no projection system, mean age 7 years 5 months; (c) Class 2, orthogonal projection, mean age 9 years 8 months; (d) Class 3, vertical oblique projection, mean age 11 years 11 months; (e) Class 4, oblique projection, mean age 13 years 7 months; (f) Class 5, naive perspective, mean age 14 years 4 months; (g) Class 6, perspective, mean age 13 years 7 months. Taken from Willats (1997, Fig. 1.9).

The children who produced drawings of the type shown at Fig. 1.1e managed to solve the problem by using a more complex rule: represent front-to-back edges by oblique lines. of all the drawing systems used by adult artists in all periods and cultures this system (known as oblique projection) is probably the most frequently used solution to the problem. In this experiment, however, drawings of this type do not correspond to the view the children were asked to draw. In drawings of the type shown at Fig. 1.1f, naive perspective, the rule has been modified by saying that diagonal lines representing edges on the left of the table run up to the right, and lines representing edges on the right run up to the left (a system used by many 14th- century Italian painters). Some of the drawings of the type shown at Fig. 1.1g, which are in true perspective, may have been produced by using a rule in which the directions of the edges of the table as they appeared in the child’s visual field are reproduced on the surface of the picture, but others may have been produced using the rule: Let the orthogonals (lines representing front-to-back edges in the scene) converge to a vanishing point. (It was the discovery of this rule that marked the beginning of Renaissance painting.) Without further experimentation, it is impossible to say which of these two kinds of rules the children were using. However, because drawings in true perspective accounted for only 6% of all the drawings produced in this experiment, it seems fair to say that the majority of the children were deriving their drawings from object-centered descriptions rather than from views.

It is clear from the results of this experiment that the older children used more complex rules than did the younger children and that as a result they were able to produce more effective representations. In this case, the drawings produced by the older children were more effective in two senses: they could more easily be recognized as drawings of a table, and they looked more like the view they were asked to draw.

Even within this experiment, however, the rules I have described are not adequate to account for all the features in these drawings. Why are the box and the radio in Fig. 1.1c shown side by side instead of one behind the other? Why are the objects in Fig. 1.1d apparently perched on the far edge of the table, and why is the box drawn in such a peculiar way? Moreover, drawing rules of this kind are not appropriate for drawing many of the objects that children want to draw, especially objects without straight edges such as animals and people. Discovering rules for drawing all these kinds of objects is a complex task for children, which is one of the reasons it takes children so long to learn to draw.

The other scientific revolution that makes this new account of children’s drawings possible was pioneered by the American linguist Noam Chomsky. From roughly the beginning of the 20th century until the 1950s, linguists argued that children learn to speak by imitating adult speech, that is, by hearing adult words and sentences in repeated association with certain events or objects, committing them to memory and the...