![]()

01

STRUCTURING INFORMATION:

— TOWARDS AN ARCHITECTURE OF INFORMATION

“Topology becomes the dominant … discipline.”

Reyner Banham, “The New Brutalism,” (1955).1

“Infolding: imagine working through into depths with the help of a media that provides instantaneous feedback and thereby allows infolding with time, memory, energy, relation… A topology that uses rhythms intermingling and flowing around and through each other would let us build walls secondarily, rather than as categorical dividers. TV networks do not have walls…”

Warren Brodey, “Biotopology 1972,” 1971.2

AN ENFOLDED MEMBRANE

— GEORGES TEYSSOT

Our starting point is a well-known story. During the 1990s, while many American architects were reading the English translation of Gilles Deleuze’s study The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque (1993), Greg Lynn edited an issue of Architectural Design (1993) on the topic of Folding in Architecture. In his introduction, “Architecture Curvilinearity: The Folded, the Pliant, and the Supple,” Lynn called for curvilinear forms.3 This invocation led to the provisional assertion of a “blob” architecture, the official birth of which seems to be marked by Lynn’s subsequent article in ANY magazine (1996), where he argued that tectonics was “out” and obsolete, while topology was “in” and sexy.4 Lynn also thumbed his nose at a series of personalities who were fighting rearguard battles, defending what remained of the idea of Semperian tectonics. Moreover, during the 1990s, new tools for 3-D modeling offered by numerous computer applications (Maya, Form*Z, Rhino) made it possible for architects to literally multiply the folds in their projects.

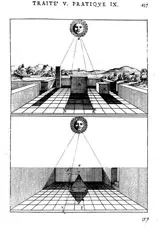

The Monad’s Window

One might ask what architects discovered in reading Deleuze’s interpretation of Leibniz, the most important aspect of which was the monad. In the Monadology (1714), Leibniz gives the name monad to the simple substance.5 This singular individuality, a folded membrane, carries all actions and thoughts that will unfold over time. Each monad collects and reflects the whole world, and operates as “a perpetual living mirror of the universe.”6 Michel Serres, in his famous thesis on Leibniz, and more recently, Bernard Cache, have argued that Girard Desargues’ mathematics provided a model for Leibniz’s monad.7 Inventor of infinitesimal calculus, Leibniz could easily have consulted Desargues’ work. An architect, engineer, and mathematician, Desargues was a founder of projective geometry, which offers a mathematical model for the intuitive notions of perspective and horizon by studying what remains invariable in projections. Outlining the concept of the “invariant,” he gives his name to the “Desargues theorem,” focusing on homological triangles. His disciple was the engraver Abraham Bosse, author of a Treatise on Projections and Perspective (1665), who later taught linear perspective to stonecutters, carpenters, engravers, manufacturers of instruments and, less successfully, to painters.8 The perspective that Bosse teaches implicitly introduces the idea of infinity, in that he uses parallel lines with an infinitely extending vanishing point to construct perspective. Moreover, permeated by the knowledge of Desargues, Bosse develops a method for tracing shadows, which was inspired by his master.9 (figs 1, 2)

fig 1

Abraham Bosse, Manière universelle de M. Desargues, pour pratiquer la perspective par petit-pied… (Paris: P. Deshayes, 1648), p. 100. Courtesy Werner Nekes Collection, Mülheim/Ruhr, Germany.

fig 2

Jean Dubreuil, La perspective pratique, nécessaire à tous peintres, graveurs, architectes, brodeurs, sculpteurs, 2nd edition (Paris: Chez Jean Du Puis, 1664). Courtesy Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France, Institut de France, Paris, France. Photo: Réunion des Musées Nationaux (RMN) / Art Resource, NY.

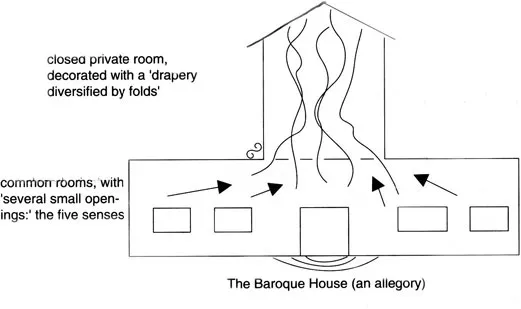

It remains to succinctly describe The Monadology, which is a synthesis of the Leibniz’s thought. A monad is “a simple substance … that has no parts,” for monads constitute “the true atoms of Nature”.10 Natural changes and transformations in a monad occur as a result of “an internal force, which one might call an active force.”11 A monad is the site of changes in “what we call perception.”12 To describe monads, Leibniz introduces the Aristotelian notion of Entelechies, actuality, from entelekheia – active, effective energy. For Aristotle, the soul is the entelechy of the body. It is where the sources of the body’s internal activities reside, guaranteeing them a certain perfection, assuring them an autonomous existence (autarcheia), and allowing them to act like “immaterial automata.”13 Nature has given highly effective perceptions to animals that correspond to each of the five senses, as well as other senses that man does not comprehend. Animals are provided with sense organs and “what happens in the soul represents what goes on in those organs.”14 The lower animals possess empirical knowledge every bit as much as man does, but man is endowed with Reason, and can acquire Science, for we are dealing here with what is called a “‘rational soul’ or ‘mind’ in us.”15 Atoms, which are all different, come together to create the whole array of bodies found in nature, whose movements God orders so as to produce the best of all possible worlds.16 It follows that “this interconnection, or this adapting of all created things to each one … brings it about that each simple substance has relational properties that express all the others, so that each monad is a perpetual living mirror of the universe.”17

To explain the paradox of the diversity of worlds, where each monad represents the universe, only differently, Leibniz uses the example of point of view: “Just as the same town when seen from different sides will seem quite different – as though it were multiplied perspectivally – the same thing happens here: because of the infinite multitude of simple substances it’s as though there were that many different universes; but they are all perspectives on the same one, differing according to the different points of view of the monads.”18 This is, of course, an allusion to anamorphoses, curiosities typical of the baroque, defined by the play of perspective obtained by a reflection in a curved mirror or through a mathematical procedure, that only reveal a drawing’s subject when the viewer stands in a particular spot. “Each body feels the effects of everything that happens in the universe,” and this, everywhere, whether in the past or the present, extends to “what is distant both in space and in time,” writes Leibniz.19 Hippocrates liked to say that there is one common flow, one common breathing, and all things were in sympathy: “But a soul can read within itself only what is represented there distinctly; it could never bring out all at once everything that is folded into it, because its folds go on to infinity,” writes Leibniz.20 Bodies are folded substances every bit as much as souls are; but, like a hyperbola, the fold of souls goes on toward infinity. “Thus, although each created monad represents the whole universe, it represents more distinctly the body that is exclusively assigned to it.”21 The monad – and this is the paradox – is a living mirror of the universe, but it also possesses an “organized body,” a kind of “divine machine or natural automaton.”22 The monad is alive and is endowed with a capacity for internal action, capable of representing the world from its particular point of view. As a “Living Mirror,” it is regulated by harmonic relations, and ordered like the universe. For Leibniz, substance being in a “perpetual state of flux,” the monad acts as a medium.23 Yet, monads have no causal interactions among themselves, nor do they interact directly with real phenomena, perceived jointly with the other monads. Hence the paradox: “perception” provides the very substance of the monad, but without any external influence.24 Like automatons moved by a spring, all created monads have internal perfection, which ensures their autonomy. They are self-sufficient.

fig 3

Allegory of the Baroque House, in Gilles Deleuze, The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, trans. Tom Conley, [1988], (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 5. Courtesy of University of Minnesota Press.

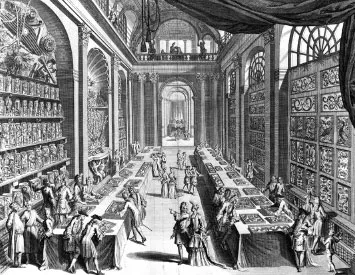

fig 5

View of a curiosities cabinet (Wunderkammer) from: “A series of illustrations…of Levin Vincent’s collection”, in Levin Vincent, Wondertooneel der nature [Marvels of Nature] (Haarlem: Sumptibus Auctoris, 1719). Photo: Snark / Art Resource, NY.

During the seventeenth century, with René Descartes and Blaise Pascal, geometry is one of the most innovative aspects of science, and it governs the spirits. As Michel Serres explains in Le système de Leibniz (The System of Leibniz, 1968), amongst geometry’s applications are perspective and its inverse – the tracing of shadows, which was useful for painters, engravers, and architects. Leibniz seeks to connect with an assortment of encyclopedic knowledge, at the center of which one discovers the epistemology of Desargues’ work. Leibniz’s terminology reflects Desargues’ principles – while at the same time drawing upon his own philosophical language, which allows one to ask if Desargues’ principles are indeed the models of Leibniz’s categories. This questioning would indicate one of the sources of the Leibnizian system. As Serres wrote:

“One knows how to ‘concretize’ a point of view, a place and a situation, an elevation (figure and situation of an object), the determination of a correspondence, the relation of appearance between an objective point and a prospective point, the character of representation of this appearance, and so on. Everything happens as if the reasons and principles of perspective … were epistemologically expressible in a language that is none other than the philosophical language of the Monadology.”25

Serres warns, however, that there isn’t a single model: “This does not imply that The Monadology is only a metaphysical translation of Desargues’ epistemology.… [T]here are also other translations; the perspective template is just one model among others. From this model to the structure of The Monadology, there isn’t a one-to-one relation, but a one-to-multiple relation.”26 For Cache, it is not sufficient to merely affirm that the monad is a viewpoint on the world; one must provide a geometric construction that implements a principle internal to the monad’s closed box, in accordance with Alberti’s perspective, which presented the capacity to connect objects and subjects in space.27 For Leibniz, in their completeness, “monads have no windows, through which anything could come in or go out”28 – although Horst Bredekamp challenges this assertion in his book, The Window of the Monad (2008).29 The first stage of Leibniz’s monad, described in a drawing of 1663, represents the relations between soul and body with the shape of a Pythagorean pentagram.30

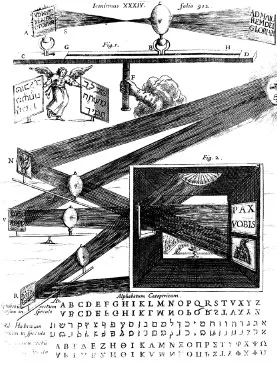

fig 6

Projecting inscriptions through a set of lenses; in Athanasius Kircher, Ars magna lucis et umbrae (Rome: H. Scheus, 1646), 912, p. 34. Courtesy Werner Nekes Collection, Mülheim/Ruhr, Germany.

As Deleuze writes in The Logic of Sense (1969), “This surface topology, these impersonal and preindividual nomadic singularities constitute the real transcendental field.”31 For Leibniz, “the individual monad expresses a world according to th...