![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Collaborative consultation in mental health

Glenda Fredman, Andia Papadopoulou and Emma Worwood

We, the authors of this book, have been working for many years as clinical psychologists with people with health, mental health and social care problems. Our posts within public health and social care services have involved consultation with staff within different agency contexts such as schools, day centres and hospitals, which provide services to a range of client groups including children, adolescents, adults, older people and people with intellectual disabilities. Over the years, like many other professionals within public services, we have experienced increasing demands to ‘share’ our expertise, including ideas, theories, skills and experience, with those who are engaged in ‘direct’ face-to-face work. In the current climate of limited resources for and increasing demands on mental health interventions, this sort of ‘indirect’ consultation is receiving growing recognition for making a relevant and important contribution.

When we (Andia and Emma) and our clinical child psychology colleagues started to respond to requests for consultation several years ago, we all had completed rigorous training to doctorate level and acquired our professional skills and expertise under years of close supervision. At that time, like many of our colleagues, we held the view that practitioners who are adequately trained to provide a direct (clinical) service are also adequately prepared to support or develop the clinical practice of others; so we assumed that our consultation skills would come to us naturally or intuitively. When we started working with practitioner-consultees such as nurses, health visitors and teachers, however, we immediately recognised that consultation is different from many other areas of practice because of its indirect service delivery approach. We found that our mental health professional trainings had not equipped us to make the transition from practitioner to consultant and that consultation was definitely not as straightforward as it looked. Also, it soon became apparent to us that the staff and teams with whom we were consulting had considerable expertise in their specialist areas of practice. Being positioned as ‘the expert’ did not sit comfortably with us when the people with whom we were consulting often had more experience than we had, as newly qualified clinicians. Therefore, we wanted to learn how to work collaboratively with people in consultation, in ways that we could honour and make use of their wealth of skills, knowledge and experience.

How this book came about

Like many consultants of our time, we had to learn the practice of consultation on the job (Greiner and Ennsfellner, 2014), and so turned to the available literature to help us. We found texts on ‘what is consultation?’ (Casey et al., 1994; Dougherty, 2013), ‘how it differs from supervision’ (Lake et al., 2008) and ‘why and where to use consultation’ (Crothers et al., 2008), but no book to help us develop a practical competence in collaborative consultation. Over the following years, we met regularly with other ‘novice consultants’ to support each other on moving positions from clinical practitioner to consultant. We explored ethical and practical dilemmas involved in the process of consultation, such as the challenges of entering new organisations and systems and the ‘meeting of worlds’ between health, education, social care and the voluntary sector.

We have written this book because it is the book we authors were looking for when we started consultation, the book we had wished we had on our bookshelves and would have liked to recommend to new consultants. We invited our colleagues working in services for older adults (Eleanor Martin and Alison Milton, Chapter 10) and for adults with intellectual disabilities (Selma Rikberg Smyly and Sarah Coles, Chapter 8 and Joel Parker, Chapter 9) to join us in this writing project as they were developing approaches to collaborative consultation in their contexts of practice.

Consultation on consultation

I (Glenda) was invited by the manager of Andia and Emma’s child mental health service to ‘train’ the clinical child psychologists in consultation. Since they were already offering consultation to schools, health visitors and children’s centres, we all agreed that I would take the position of ‘consultant’ and offer ‘consultation on consultation’. I created opportunities in this group for the new consultants to experience various consultation approaches by inviting them to bring their consultation work, including dilemmas and examples of interesting or inspiring practice, to the group for consultation. I positioned myself as the interviewing consultant and invited the group members to observe the process of the consultation, stopping the action from time to time so they were also able to ‘reflect on the action’ of the consultation while ‘in action’ (Schon, 1987). Thus my practice as consultant mirrored the consultation approach and methods the group were experiencing and learning about.

With our colleagues, we (Andia and Emma) derived considerable support from our ‘consultation on consultation’ groups with Glenda. Like Preedy (2008), as new consultants, we found it extremely valuable to have protected time to consider our consultation practice, with opportunities to reflect on our developing competence and identity as consultants. We supported each other by sharing stories of our own consultation practice as well as experiencing, observing and practising consultation methods and skills. We connected our learning with collaborative, systemic, narrative and appreciative inquiry approaches, which over time became a common frame of reference that informed our ongoing consultation practice.

As the group gained confidence and skill through experiencing and observing consultations, group members began to take on the position of consultant to each other using ‘practice guides’ we had generated of key steps in the consultation process (p. x). When group members took the position of consultant, I (Glenda) moved position to ‘live-supervise’ their consultation practice in action and positioned some of the group as co-consultants to support the interviewing consultant, thereby using the group as a resource to the consultation process (Chapter 7).

I (Glenda) invited group members to document examples from their ongoing consultation practice and keep written records of their ‘learning points’ that emerged in each consultation on consultation session. We (Andia and Emma) chose to call these learning records ‘minutes’; recording our learning enabled us to become observers to our consultation practice and thereby develop reflexivity. Our ‘minutes’ and learning records sparked the conception of this book and went on to inform our writing so that the questions and dilemmas presented in this book as well as the resolutions and possibilities are all grounded in practice.

What is consultation?

The word ‘consultation’ has many different meanings in different contexts. Most people will be familiar with the terms ‘consultation’ and ‘consultant’ used in a medical context to denote a meeting with an expert, usually a medical doctor, in order to seek advice or treatment, and the use of the title ‘consultant’ to denote a position of seniority within a profession, as in ‘consultant clinical psychologist’ or ‘consultant psychiatrist’. Nowadays, the term consultant also appears in many other everyday areas of life such as ‘financial consultant’, ‘wedding consultant’ and ‘travel consultant’ (Gibson and Mitchell, 2008). Within mental health services, consultation has been viewed as offering thinking space to help practitioners use psychological frameworks to reflect on specific clients and develop their own skills (Preedy, 2008) and as an enquiring and reflexive approach to reviewing the work between a practitioner or team and a ‘client’ or ‘service user’ (Lake, 2008). Therefore, consultees with whom we meet might hold a range of different meanings for ‘consultation’. For example, in Chapter 2, teacher-consultees anticipated judgement (‘tell us what we do wrong’) and criticism (‘being disciplined’); in Chapter 3, health visitor-consultees expected expert advice, solutions and ‘all the answers’, and a child-care worker was looking for a five-minute ‘chat’; in Chapter 4, child-care workers were ‘looking forward’ to ‘time to stop and think’, and possibly skills training.

Since the people commissioning consultation are not always clear about what they themselves want or expect from ‘consultation’, we try to engage commissioners and managers in a process of co-contracting to clarify together what the work involves (Chapter 2). With consultees, we take care with how we name and describe what we will be doing together by checking and coordinating our meanings of ‘consultation’.

Going inside ‘consultation’

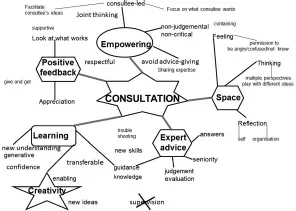

If the work has already been ascribed the name ‘consultation’, we often begin with ‘going inside the word’ (Andersen, 1995; Fredman et al., 2010) ‘consultation’ to explore the meanings ‘consultation’ holds for the consultees. Sometimes we create a mind-map or linguagram (Lang and McAdam, 1996; Partridge, 2010) with consultees to explore what meaning they are giving to ‘consultation’. Figure 1.1 shows an example of a linguagram we created at the start of our consultation on consultation groups in response to the question: ‘what is consultation?’

Figure 1.1 Linguagram of ‘consultation’

Starting with the word ‘consultation’ in the centre of the whiteboard, I (Glenda) invited the group to ‘Look inside the word consultation … what do you see? … What do we mean by “consultation”? …. What sense do our consultees and commissioners make of the term “consultation”?’ As the consultees generated words and phrases, I added them to the emerging mind-map, checking with the consultees each time whether their new ideas ‘fit’ with their previous ideas or were a departure. In this way, we grouped ideas, meanings and concepts into themes that connected with each other, thereby constructing a common language between us. By moving words and ideas around the board, we created opportunities for new meanings and perspectives to emerge and were able to elaborate the meanings we were giving to ‘consultation’.

Mapping the meanings of ‘consultation’ in this way can create the opportunity for consultees to share previous experiences and expectations of consultation, giving us some understanding of their relationship to consultation. This process can open space for consultants and consultees to negotiate how we can work collaboratively with each other, to clarify what consultees want from the consultation as well as the rights, duties, opportunities and constraints in the process. Sometimes we invite consultees to jointly co-create a name for the consultation work as a way of beginning our work together, simply asking ‘What shall we call our work together?’

Distinguishing consultation from supervision

The word ‘supervision’ is derived from the Latin super (over) and videre (to see), implying both a ‘seeing’ from a ‘higher’ vantage point and an ‘overview’ or ‘watching over’ (Bownas and Fredman, 2016). Therefore implicit in the term ‘supervision’ is a monitoring function, accountability and the expectation that the supervisor is more experienced and trained in the work that the supervisee is undertaking. The word ‘consultation’ is derived from the Latin com (with) and selere (take, gather [the Senate] together), and also the Latin consultare ‘consult, ask counsel of; refl...