![]()

Part I

Chicana/o history and social movements

Introduction

The field of Chicana/o history strives to recover and critically analyze the past through the optics of social history, borderlands theory, herstory, myth, and critical race theory. Chronology matters but above all what counts is identifying key events, sociopolitical conditions, and people that provide insight into the historical unfolding of the development of Chicana/o communities across the United States. This section offers diverse methodologies and interpretations of historical events and narratives that both bind and separate people of Mexican-descent across generations and geographic spaces. Essays in this section reveal Chicana/o history by defining fundamental parameters of what constitutes such a history through reevaluations, redefinitions and revisionism. Changes and choices in ethnic self-identifiers from Mexican to Chicano to Chicana/o to Hispanic or Latina/o are used throughout each essay to remind us of the diversity within Mexican-descent communities. The importance of queer identities (which includes gays, lesbians, bisexuals, transgender individuals, and all gender-nonconforming people) within the context of Chicana/o history and social movements is also introduced and will be examined further across the Handbook.

Documented history is wide-ranging and robust within U.S. history, but essays here remind us that substantial popular history exists that has remained either obscure or unspecified. These entries offer detailed accounts from various fronts, including the essential concept of genealogy and origins that show that Chicanas/os did not emerge in the 1960s. Rather, the development of Mexican and Chicana/o communities is complex and interwoven with conquest, colonization, and resistance that extends from the mid-sixteenth century through the Colonial Period (1528–1821) to the present time. Chicana/o history was obscured by the dynamics of conquest and annexation of half of Mexico due to the U.S.-Mexico War of l848. Integral to understanding Chicana/o history is reconsidering the narrative of Aztlán (the Aztec homeland) which predates the European incursion into northern Mexico, or what after 1848 became the U.S. Southwest.

The entries authoritatively document important aspects of Chicana/o history, such as assessing historical agency via foundational methodologies: the generational approach, an analysis of the Chicano movement, analysis of Chicana voices challenging male-dominated discourse and politics, particularly in the Chicano movement (or movimiento) and other social spaces. Other entries examine bilateral cultural connections with Mexico, the ubiquitous (im)migration ebbs, flows and patterns and the barriers to educational equity. The section, then, focuses on a wide variety of social events and movements that navigate the paradigms of internal colonialism, postcolonialism, cultural nationalism, labor and educational movements, Third World feminisms, transnationalism, and the myth of origins.

![]()

1

What is Aztlán?

Homeland, quest, female place

David Carrasco

A significant part of writing and public attention on Aztlán especially since the proclamation of El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán has been concerned with where Aztlán was. Was it in a specific geographical location in northern Mexico or somewhere in the Southwestern part of the United States or lodged in the hearts and minds of our Mexica (generally known as Aztecs) forbears and now Mexican Americans? Even when Aztlán is viewed more broadly in terms of art, migratory space or cultural contact a preoccupation with the geographical location of the Aztec place of origins is evident. For instance in the landmark book The Road to Aztlán: Art from a Mythic Homeland (2001) that accompanied a stunning art exhibition of the same name at LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art 2001), the editors achieved a near magic trick by both ‘deterritorializing’ and ‘reterritorializing’ Aztlán. On the one hand, they included essays and art that encompassed the American Southwest and portions of Mexico showing that Aztlán is not a specific historical location at all but refers to a huge geographical area where people, objects, ideas, and meanings traveled and were exchanged over enormous distances and punishing terrain. On the other hand, in the last section of the book we see Aztlán “re-territorialized” in a series of specific Chicano locations where artworks in exhibitions and public walls in various Chicano and other communities show that multiple but specific Mexican American homelands, Aztláns all, exist. As one cultural critic says Aztlán refers “to all those places where there is a strong Mexican and Chicano/a cultural presence” (Fields & Zamudio-Taylor 2001, p. 42).

What is clear is that Aztlán is a very Mexican story. Mexican in the pre-Hispanic sense, Mexican in the colonial sense and Mexican in the Mexican American sense. The power of Aztlán to reach across centuries and cultures came clearer when I met Eduardo Matos Moteuczoma1 in 1979, the director of the Templo Mayor excavation in the Zócalo of Mexico City:

I want you to help me understand something that is strange to me. Since the excavation started to get press in the United States, I get calls every week from Chicanos who claim they feel some deep connection to the Templo Mayor. They call from Houston and San Antonio, even Chicago, talking about Aztlán and Moteuczoma, Cuauhtémoc, and I’m not sure what to tell them.

(Carrasco 2003, p. 177)

Matos Moteuczoma was incredulous and said,

Some claim that the Aztec place of origin Aztlán, is in New Mexico, but we in Mexico know that Aztlán was much closer to Tenochtitlan. As you know, most Mexicans who migrate to the United States do not come from the territory of the Aztec empire. Can you help me understand this and get in touch with Chicanos who think this way?

(Carrasco 2003, p. 177)

Much less work has focused on what is an even more important question. WHAT was Aztlán? What kind of place was it? Did its power arise from its prestige at the ‘center’ of a cultural narrative? Or was it significant for the opposite reason – that is, it was located on the periphery of an ancient civilization and produced iconoclastic and new cultural powers? What was the social, political and spiritual source of Aztlán’s significance for the Mexica? What were its magical powers? What deeper motivations in us have led to it becoming a major and enduring symbol of our place and identity in North American society? If the places we come from shape our memories, families, identities and even destinies, then knowing the powers and significance of Aztlán is as important as pinpointing it on a map. As the very extensive bibliography of Aztlán shows, it is an example of topophilia (Tuan 1974, p. 76), a powerful emotional and social bond between a people and their sacred place. Many Chicanos display affection, fascination and a mental orientation for Aztlán as a mythic place and as local places they name Aztlán or compare to Aztlán. Over time this supremely Mexican American place has become mixed with a sense of origins, ethnic identity and, in some cases, cultural destiny. Exploring this question of “What was/is Aztlán?” will help us understand better the secret meaning in Rafael Pérez-Torres’ claim about Mexican Americans that “Aztlán is our start and end point of empowerment” (Pérez-Torres 2001, p. 235).

Aztlán and human needs

In its heart, Aztlán is about three human needs. The need for place, the need for journey and the need for female presence. First, Aztlán is about ‘orientation’, a sacred homeland; that is, the need to know you came from a place where your ancestors cared for each other amid stability and crisis. For our Mexica ancestors, that place was an enchanted cave, sometimes divided by seven, eight or nine internal niches surrounded by a garden/lake world. The second need, evident in most of us when we are teenagers or young adults, is the need to take a journey away from home to map a wider world and establish a new identity beyond our family home. This need to confront what Octavio Paz calls “the infinite richness of the world” (Paz 1985, p. 9) results, as in the Aztlán story, in pilgrimages across wondrous and hazardous landscapes. Paz is here celebrating the possibilities of the journey, the quest at the heart of human yearnings for life heading towards the horizons which is part of the Aztlán archetype. The surviving texts show us that for some Aztlán is the starting place. For others it is the home at the end of the rugged road. Third, the Aztlán story, at least in the two versions recounted here, is about the powers and prestige of females who occupy the center of the world in different ways as mothers or warriors. They lead the ancestors on a journey outward and call them home again. Yet, for decades this feminine aspect of the Aztlán narrative has been largely unnoticed. Perhaps this aspect of the ancient Aztlán story contributes to and reflects the deep communion Mexicans seek with their mothers and motherland

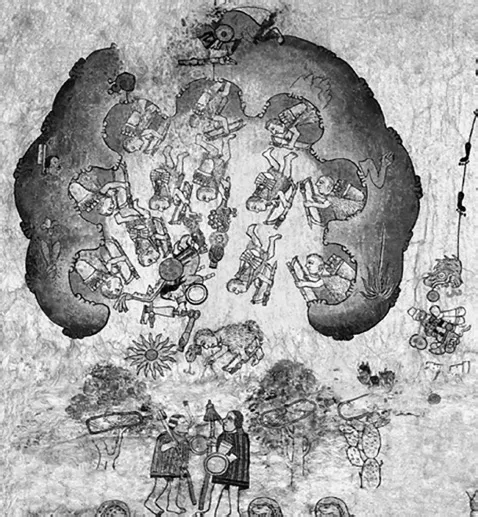

In the Chicano movement, females were often relegated to the periphery of the political action, restricted in opportunities to lead and seldom given credit for their ingenuity, courage and strength. Aztlán was often proclaimed and dreamed of in those days as a male-oriented story, spoken of in a masculine voice, led by males who felt the need to dominate the Chicano hunger for social justice and search for political vindication. Yet, as we shall see, these two Chicomóztoc/Aztlán stories, reported and painted by Indigenous Mexicans during the early decades of the colonial period, show us that female figures with the qualities of caring, prophecy, courage and the ability to fight back are key parts of the answer to the question, “What is Aztlán?”2

Simply stated, Aztlán is one version of a native Mexican archetype of origins – a patterned, mythical way of thinking about the emergence of ancestors from an original, precious homeland in the forms of caves/grottoes within an enchanted hill (Carrasco 2014). The more widely shared name for this archetypal hill was “The Place of Seven Caves” or Chicomóztoc (Image 1.1). Some ethnographic texts tell of six or eight or even nine caves. But this variety is less significant than the hypnotic imagery of courageous ancestors first dwelling productively within the natural architecture of the hill/lake or mountain of water and then emerging under the spell of a divine message to journey to a new homeland. This is the pattern that, in spite of regional variations and historical disruptions, was chosen by Native storytellers and painters to shape the story of epic ancestral journeys. The Náhuatl term for this kind of place is altepetl or mountain of water. The fuller meaning of altepetl is place of nourishment, protection, inspiration and support. It is the archetype of original sustenance and protection of the Place of Seven Caves that is most profoundly registered in the two versions to be examined here. And it is this protection, sustenance and female support that Mexican Americans have sought (consciously and unconsciously) and celebrated through their fascination with Aztlán.

Image 1.1 Chicomóztoc (“The Place of Seven Caves”)

Aztlán stories and images survive the fires

That the Aztlán story and imagery survived Catholic inquisitional attacks against Indigenous libraries and storytelling is something of a tragic literary miracle. Of the thousands of Mesoamerican codices, maps and other pictorial documents extant at the time of the Iberian-Indigenous encounter of the 1520s, only 15 pre-Hispanic documents have survived and perhaps only one is from the Aztec tradition. The famed art historian Elizabeth H. Boone tells us of the uniqueness of this pictorial tradition:

Mesoamerica is unique [in] the Western Hemisphere… . In Aztec Mexico the manuscript painter was the tlacuilo, a term translated as both ‘painter’ and ‘scribe’. Those who determined the intellectual content of the more esteemed codices – the authors of the histories and religious books – went by the term tlamatini (sage).

(Boone 2001, pp. 454–456)

Catholic priests hunted down rumors of Native manuscripts and destroyed them whenever possible, sometimes in fiery public displays meant to humiliate and intimidate the Indigenous populace and put an end to knowledge of pre-Hispanic religious and cultural practices. In effect, the Catholic purpose was to destroy the Indigenous models of thinking and rites of passage. Their goal was to obliterate the Native archetypes of world creation, world order, divinities and cosmology. Nonetheless, surviving Native storytellers, painters and sages in the colonial period continued to narrate, draw and paint pre-Hispanic epics and local accounts of world creations and destructions, migrations, epiphanies and histories. Fortunately, two of the early colonial documents, one written by a Dominican priest and the other by anonymous Indigenous painters, have survived to tell the Aztlán/Chicomóztoc story with its three human needs in remarkable imagery and diversity. In what follows will be the summary and interpretation of these Aztlán stories and imagery found in: 1) chapter 27 of Diego Durán’s History of the Indies of New Spain; and 2) in the opening hieroglyphs of the beautiful and recently rediscovered Mapa de Cuauhtinchan #2. These two documents provide insights into “what” Aztlán actually was and why its paradigmatic power has been influential to Indigenous identity and worldview from the pre-Hispanic periods up until today when Mexican American cultural practices include nostalgia for migrations to and from a paradisiacal place where powerful women beckon.

Diego Durán’s Aztlán and the divine mother at the sacred hill

It took the persistent, long-distance walking of Diego Durán, a Dominican missionary and historian, to recover the single most elaborate Indigenous version of the Aztlán story. Durán came to New Spain from Seville around 1543 at the age of 7 and he grew up bilingually, speaking Náhuatl and Spanish. His ministry among Náhuatl-speaking peoples, mestizos and Spaniards showed that he was “interested in the activities and beliefs of everyone he met: the market people, the Indians who cut wood in the forest, or the women who served as family domestics and who had once been branded as slaves” (Heyden 2001, pp. 81–110). Believing that the successful evangelization of the Natives in New Spain depended, in part, on gaining “more knowledge of the language, customs and weaknesses of these peoples” (Ibid., p. 95), he sought out local surviving Native historians and especially those suspected of guarding pictorial manuscripts (including those produced in secret during the early colonial period). His research and interviewing of elders in different communities in the Valley of Mexico resulted in three invaluable books, one of which included the most elaborate Aztlán story of all, The History of the Indies of New Spain published in 1581. Chapter 27 of this invaluable book begins: “King Moteuczoma the First, now reigning in glory and majesty, sought the place of origin of his ancestors, the Seven Caves in which they had dwelt. With a description of the splendid presents he sent to be given to those who might be found there” (Durán 1994, p. 212).3

We are told that Moteuczoma the First (Moteuczoma Ilhuicamina and not Moteuczoma a Xocoyotzin who ruled at the time of the Spanish invasion), who ruled from 1440–1468, planned to send warriors with gifts to the ancestral lands of Chicomóztoc, the Place of Seven Caves, to communicate with the still-living “mother of our god Huitzilopochtli.” But Moteuczoma’s second in command, Tlacaelel, intervenes, saying to substitute wizards, sorcerers and magicians in place of warriors because the former have enchantments and spells to help them “find that place … where our god Huitzilopochtli was born” (Durán 1994, p. 213) in a delightful marshy lagoon where ancestors never grew old or tired or lacked for anything. Hearing this story of natural abundance, Moteuczoma calls upon his royal historian Cuauhcóatl (Eagle Serpent) to provide knowledge “hidden in your books about the Seven Caves where our fathers and grandfathers came forth … wherein dwelt our god Huitzilopochtli and out of which he led our forefathers” (Durán 1994, p. 213).

The royal historian consults the pictorial manuscripts and describes for the ruler the true nature of Aztlán with crucial details. He reports that the ancestors dwelt in a blissful happy place called Aztlán, which means ‘Whiteness’. In that place there is a great hill in the midst of the waters, and it is called Colhuacan because its summit is twisted. In this hill were caves or grottoes where our fathers and grandfathers lived for many years. There they lived in leisure, when they were called Mexitin (or Mexicas) or Aztecs. They had at their disposal great flocks of ducks of different kinds, herons, cormorants, cranes and other waterfowl. Our ancestors enjoyed the song and melody of the little birds with red and yellow heads. They also possessed many kinds of large beautiful fish. They had the freshness of groves of trees along the edge of the waters. Our ancestors went about in canoes and made plots on which they sowed maize, chiles, tomatoes, amaranth, beans and all kinds of se...