![]()

Chapter 1

Preface: We Are Here

The 2014 NYC mayoral transition from the era of Michael Bloomberg’s administration to the new one headed by Bill de Blasio took place in the midst of an ongoing economic, cultural, ecological, and political crisis. At the same time, the NYC Department of Planning released The Newest New Yorkers, 2013 Edition, which prompted wide media coverage reporting that more foreign-born legal immigrants “live in NYC than there are people in Chicago,”1 some three million individuals, or thirty-seven percent of NYC residents. The largest groups of these new urban citizens are from the Dominican Republic, China, and Mexico, and a great majority has immigrated since early 1990s. Most have limited English language proficiency and make between thirty-five and seventy percent of the city’s median family income. Two thirds live in Brooklyn and Queens, and along B, Q, N, and 7 subway lines in urban territories predominantly populated by immigrant groups, situated outside of the main corridors of commodity and capital flow, and at the receiving end of little to no improvement in municipal services and capital investments under the Bloomberg administration.

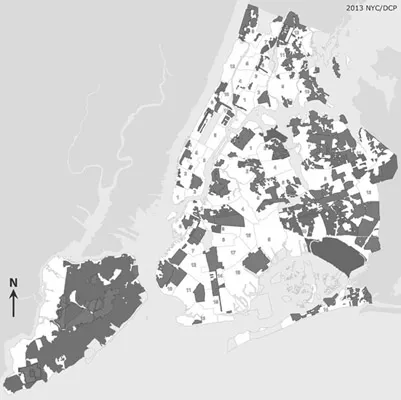

In large part, Mayor de Blasio won the election by forcefully and rightfully criticizing Michael Bloomberg’s neoliberal policies, particularly in relation to urban development. His political campaign was centered on fighting urban inequality as exemplified by “the tale of two cities” slogan.2 After all, Bloomberg’s rezoning of nearly forty percent of the city’s most commercially promising land is an act of historic proportions (Figure 1.1).3 Rezoning it for the purposes of further commodifying urban space without significant public participation in the process is an act of wicked proportions. Even though some progress was made in areas such as public health, civic architecture, and environmental protection,4 the Bloomberg administration’s vision of urban development was firmly based on the synergies between neoliberal land-zoning policies, private ownership, and hyperinflated real estate values. As such, it encouraged foreign investments, induced wholesale gentrification, naturalized mass displacement and deterritorialization of low-income residents,5 and established stop-and-frisk policing as a way of managing social, racial, and class conflict in the city.6 As expected, The New York Times poll, conducted four months before the end of his last term as mayor, revealed that New Yorkers were deeply conflicted over Michael Bloomberg’s legacy.7

When Mayor Bloomberg took office on January 1, 2002, he inherited an enormous budget deficit of over US$3 billion. In January 2014, he left office with an astounding US$2.4 billion budget surplus.8 However, during his twelve years as mayor, NYC became one of the most inequitable cities in the United States: the top 1 percent of the city’s residents made over 30 percent of its total personal annual income as the number of billionaires residing in NYC rose to 103, more than in any other city in the world.9 When Bloomberg became mayor, 1.6 million New Yorkers lived below the poverty line (20.1 percent),10 while in his last year in office 1.7 million New Yorkers fell below the official federal poverty threshold (21.2 percent).11 Between 2002 and 2013, the number of homeless New Yorkers registered for overnight stays in shelters rose from 25,000 to nearly 68,000, with more than half of the homeless population being entire families.12 “What a shameful record,” observed Brian Lehrer, host of the WNYC/NPR The Brian Lehrer Show, “that we have a record number of homeless people living in shelters today, of all times in the city’s history, when there is so much wealth, so much prosperity, when neighborhood after neighborhood is gentrifying.”13 John C. Liu, a democratic NYC comptroller during the Bloomberg administration, argued in 2012 that New York City’s economy “would be healthier and more dynamic if the benefits of growth were more fairly distributed.”14

Figure 1.1 New York City Department of City Planning Rezonings 2002–2013. Used with permission of the New York City Department of City Planning. All rights reserved.

The Bloomberg administration’s modus operandi of economic development is best described by the principle of “accumulation by dispossession” (Harvey 2003, 2007).15 Julian Brash called it “The Bloomberg Way,” the epitome of neoliberal urban governance in which the mayor is cast as CEO, the city government as a corporation, businesses as clients, residents as customers, and the city itself as a product (Brash 2011). As The New York Times reported, Bloomberg’s own observations on the effects of his policies on poor and the underprivileged New Yorkers ranged “from thoughtless to heartless.”16 His administration’s view of urban development was formulaic at best. Its political imagination was bound by economic confidence in the idea that city building is the tour de force of capital accumulation and of production of supreme surplus values (Smith 2008). In Manhattan, luxury buildings by starchitects, such as Daniel Libeskind, Frank Gehry, David Adjaye, Herzog and De Meuron, Jean Nouvel, and Renzo Piano, decorated the skyline of the ambitious global city. Ultra-expensive public projects showcased two important beliefs of Bloomberg’s administration: first, the superiority of public–private partnership as the model for private management of public resources and second, the belief in the efficacy of strictly managing public space for the purpose of attracting continued investment in real estate and driving up its value. For both to work, public spaces had to be disabled as sites of collectivization for building citizen alliances and for the politicization of everyday life; instead, a spectacularization of the commodified public encounter that has been carefully choreographed with Jan Gehl as the chief consultant for the “pedestrianization of Manhattan.”17 Similarly, “urban beautification” projects were encouraged and supported, such as the one launched by The Fund for Park Avenue and the Department of Transportation with sculptures by Albert Paley, Alice Aycock, and others installed along the Fifth Avenue median.

In the other boroughs, Department of City Planning practiced both “downzoning” and “upzoning.” In neighborhoods where real estate and land values had skyrocketed, downzoning was meant to reinforce and preserve “neighborhood character” by limiting new construction and codifying the existing urban fabric, all in order to empower building owners to keep the neighborhood from changing. Through the practice The New York Times called “downzoning uprising,” communities practiced downzoning to preserve “moderate density,” avoid crowding local schools, and, in many cases, to avoid immigrant influx.18 In parallel, the upzoning and “revitalization” of the Brooklyn–Queens waterfront had facilitated developments like the Industry City in Sunset Park,19 the Navy Yard Industrial Park in Brooklyn,20 and Long Island City in Queens,21 all reusing the dilapidated industrial facilities to boost the birth of creative industries and the technology sector. It has also scaled up the construction of luxury residential properties along the waterfront, often mixed with creative industry, such as Richard Rogers-designed Silvercup West, a US$1 billion development south of the Queensboro Bridge in Queens. Since all of the new waterfront developments are, in part, financing the development of publicly-accessible promenades and linear parks, it remains to be seen how degrees of public access will be designed and managed on the ground.

Most importantly for this book, the Bloomberg administration had also naturalized the role of “design”—including architecture, urban design, spatial planning, product and interior design as well as public art and much of the crafts under one umbrella—as “disciplinary technology” (Deutsche 1998; Foucault 1975) whose purpose is to enable economic power to be exercised strategically and differentially, and to subject urban citizens to a view of citizenship and civility framed by consumption (Zukin 1995). As such, design is mandated as a form-giving practice in which form follows fiction, finance, fear (Ellin 1996: 133–181), and the logic of profit and capital accumulation (Harvey 1991). The role of design (and public art) so construed within neoliberal practice is taken to be self-evident, universal, and necessary as a central mechanism of capital valorization (Mouffe 2000, 2007). As Rosalind Deutche argued, viewed in this way, urban planning and design, architecture, and public art are employed to bring coherence, order, and rationality to the production of capitalist urban space.

An excellent example of this principle is the High Line Park,22 a 1.5 mile-long linear park built on the derelict elevated New York Central Railway line between 2006 and 2015. The High Line showcases “an architectural theme park”23 extending south–north between Gansevoort Street and 34th Street, and blending into the Hudson Yards Redevelopment Project. Together, they form the largest private real estate development in United States history,24 and the single largest development in New York City since the Rockefeller Center was completed in 1939.25 It is undeniable that the Bloomberg administration intentionally framed (spatial) design as an instrument of capitalist organization of urban space, instrumentalized it as a tool of social control, and mobilized it as consumerist ideology. In the context of current transnational neoliberal urban developments across the globe, the practice of transfiguring projected socioeconomic realities into design has been emblematic. The role of architecture has been ultimately reduced to decoration, a Harlequin dress designed to spectacularize the scenographic effects of pseudo-urban settings and to fabricate social consensus via consumption; a consensus that, no doubt, also needs heavy policing to be sustained (Mitrašinović 2006: 271).

At the very least, these developments ask for the revaluation of the principles of representative democracy, particularly at the metropolitan and municipal levels, and above all for scrutinizing the role urban citizens play in important decision-making processes in their cities. It would be fair to suggest that concepts and practices of democracy, citizenship, participation, and design have never been more necessary or more ambiguous than today. Simultaneously, the term urban has never before represented such a rich spectrum of practices, relations, processes, meanings, and human experiences, nor has it ever before indicated such an incredible multiplicity, variety, and diversity.

In January 2015, in a somewhat delayed epilogue to Bloomberg’s plan to develop the B...