eBook - ePub

The Irish Experience Since 1800: A Concise History

A Concise History

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Irish Experience Since 1800: A Concise History

A Concise History

About this book

This rich and readable history of modern Ireland covers the political, social, economic, intellectual, and cultural dimensions of the country's development from the origins of the Irish Question to the present day. In this edition, a new introductory chapter covers the period prior to Union and a new concluding chapter takes Ireland into the twenty-first century. All material has as been substantially revised and updated to reflect more recent scholarship as well as developments during the eventful years since the previous edition. The text is richly supplemented with maps, photographs, and an extensive bibliography. There is no comparable brief, multidimensional history of modern Ireland.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Irish Experience Since 1800: A Concise History by Thomas E. Hachey,Lawrence J. McCaffrey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Irish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

From Colony to Nation-State

1

Ireland Before the Union

England’s Conquest of Ireland

Although Ireland became England’s first colony, English imperialism did not commence as a planned adventure. It began when Dermot MacMurrough went to Wales to recruit help to regain his Leinster throne, which he had lost in an Irish war. He persuaded Richard fitz Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Pembroke, known as Strongbow, a vassal of Henry II patrolling the Welsh border, to assist him. In exchange, Mac Murrough promised his daughter in marriage and succession to the recovered Leinster monarchy.

In 1169, when Strongbow’s Normans arrived in Ireland, they confronted a culturally united enemy but a country in political chaos. Whereas the rest of western Europe was developing nation-states, Ireland was divided into provincial and petty kingdoms, which in turn featured clan territories. Clannishness or tribalism assured defeat. Another factor aiding Norman victory was superior military skills, tactics, and weapons: They used armor, horses for mobility, and employed castle fortresses to secure conquered territory.

Because Irish resistance was ineffective, Strongbow’s forces moved beyond Leinster, upsetting Henry II, who feared that his vassals might establish a rival Norman-Irish kingdom on the other side of the Irish Sea. Therefore, in 1171 he came to Ireland and received homage from his vassals and some native chieftains and bishops as Lord of Ireland. In 1156, Pope Adrian IV (Nicholas Breakespear), an Englishman, had originally conferred that title on the English monarch.

Papal interference in Anglo-Irish affairs indicates that Ireland suffered from a variety of imperialisms: political, economic, cultural, and religious. Inspired by continental European models, pre-Norman Ireland was in transition. Elements of feudalism were apparent when petty kings became vassals of provincial monarchs but the latter’s powers were so evenly balanced that none of them could unify the whole country. A reformation affected Irish Christianity with the creation of diocesan structures and an importation of religious orders from abroad. Although earlier Viking invasions resulted in a sharp quality decline in Irish learning, a cultural renaissance of no small significance occurred in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. But despite Ireland’s changing character, from English and continental perspectives, it appeared a primitive, even savage place, with an archaic clan systern and a decadent, disorganized, and immoral Christianity remote from Roman authority. The Norman English hoped to seal their conquest through Anglicization and Romanization. Their colony began with an attitude of superiority over the conquered, one that persisted.

For a number of reasons, during the fourteenth century, the Norman English found themselves on the defensive. Irish chieftains adopted their military tactics and weapons. In remote areas many colonists married Irish women, adopting a Gaelic life-style, while others, tiring of Ireland’s cold and damp, returned to England. In doing so, many turned estate management over to agents, beginning a pattern of absentee landlordism. Because they remained divided, without a concept of political nationhood, the Irish failed to exploit English weaknesses and drive them out of the country.

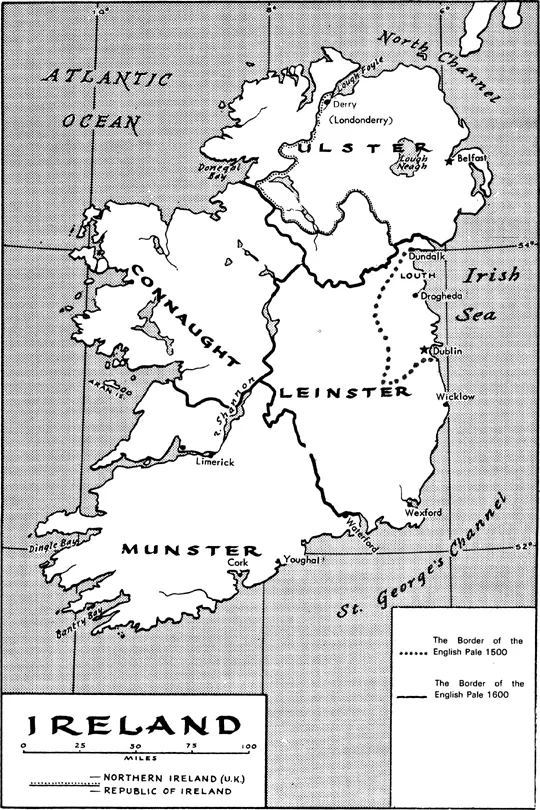

From the mid-fourteenth until the early sixteenth century, English colonists in Ireland concentrated on survival rather than expansion. In 1366, the Statutes of Kilkenny expressed defensiveness. An early example of cultural apartheid, these laws forbade associating with the Irish, marrying their women, wearing their style of dress, speaking their language, adopting their children, or seeking the services and consolations of their priests. In 1509, when Henry VIII became king of England, he was lord of three Irelands: the Pale, or Anglo-Irish-held territory, a miniature England in language, culture, and institutions; Gaelic Ireland, where native culture existed in its purest form; and an ambiguous in-between where Irish and English coexisted and sometimes blended. The Pale essentially was Leinster, Ulster was Gaelic Ireland, Munster and Connacht represented cultural assimilation.

Tudor England emerged as a significant power with a budding overseas empire, providing a rationale for increasing control in Ireland. Its monarchs decided that Ireland’s chaos and the defensive position of its colony posed a security threat to England. They feared that Irish turbulence invited an invasion threat by a continental enemy, and worried that Ireland under foreign control would endanger England by diminishing the importance of its position as an island defended by a strong navy.

Instead of spending large sums of money to stabilize Ireland militarily, Henry VIII (1491–1547) chose a more subtle strategy for extending English hegemony beyond the Pale. He persuaded clan chiefs to surrender lands to him and receive them back with territorial titles to administer as his vassals: for example, O’Neills became earls of Tyrone and O’Donnells earls of Tyrconnell. Certainly, this arrangement weakened foundations of the Gaelic order and spread common law at the expense of Brehon law. In 1541, Anglicization made progress when Ireland’s Parliament elevated Henry to king rather than lord of Ireland and when feudalism penetrated Gaelic territory. However, these innovations were more superficial than real. Outside the Pale, particularly in Ulster, Ireland remained Gaelic and politically decentralized.

Henry’s religious policy affected Ireland more than did efforts to feudalize it. In 1534, when he failed to obtain a papal annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry broke with Rome. Both the English and Irish Parliaments endorsed this move and declared him head of the Church. Because Because Henry’s rift with Rome had little relevance in Ireland, which had less loyalty to the papacy than England, Anglo-Irish feudal lords and Gaelic clan chiefs accepted the new state religion. Like the governing class throughout western Europe, Irish leaders believed that cuius regio, eius religio: People should embrace the prince’s religion in the interest of public order and tranquility. In addition, changing spiritual leadership from pope to king did not really touch people’s lives. Although Henry confiscated wealth and property from monasteries, retaining much of the spoils for the royal treasury and distributing the remainder among loyal Anglo-Irish feudal lords and Irish chiefs, his rejection of papal supremacy did not interrupt traditional Catholic devotionalism.

Long-range effects of Henry VIII’s Reformation did not become apparent until the reigns of his son, Edward VI (1547–1553), and daughter, Elizabeth I (1558–1603), when the state religion evolved liturgically and theologically into Protestantism. Most Irish (Anglo and Gaelic) were offended by this cultural attack, a more pernicious imperialism than previous English political and military adventures in their country. Irish leaders negotiated with continental powers, first Spain, then France, to support their resistance to English domination. Religious dimensions of the contest between English imperialism and Irish objection altered Irish Catholicism’s character and significance, gradually transforming it into a main feature of Irish identity, the nucleus of an incipient nationalism. Jesuits and Franciscans poured into Ireland as agents of the Counter-Reformation.

By creating an impassible barrier between English and Irish, Protestantism disrupted cultural assimilation, protecting Ireland from complete conquest by its stronger neighbor. Catholicism symbolized a besieged Irish civilization, Protestantism Anglo-Saxon aggression. While equally Irish, Anglo and Gaelic Catholic slowly melded into one identity, to uphold cultural and political autonomy, England justified conquest and control in Ireland as a protection against popery’s alien, tyrannical, and subversive presence.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, England waged war against Spain and France to achieve and maintain its status as a first-rate power. Because their enemies were Catholic, English leaders cultivated Protestant nativism as an ideology and weapon against their enemies. They also insisted that they had to conquer and subdue Ireland so that it could not host a back-door to invasion. Military strategy harnessed Protestant nativism to England’s national security, the main outlines of an Irish policy that would remain in place for centuries.

Throughout her long reign, Elizabeth coped with Irish insurrection. O’Neills, O’Donnells, and Maguires in Ulster, and Anglo-Irish Fitzgeralds, earls of Desmond in Munster, and sometimes combined forces from north and south were in revolt. In 1590, armies led by Hugh O’Neill and Hugh O’Donnell, assisted by Spanish intrigue and intervention, came close to victory. O’Neill’s guerrilla tactics and his troops, trained in up-to-date weaponry, baffled Elizabeth’s generals, Sir Henry Bagenal and the earl of Essex. In August 1598, his startling victory at Yellow Ford frightened England’s government and inspired support for independence in Ireland.

The Borders of the English Pale, 1500 and 1600

In 1601, Spain sent four thousand troops to assist the Irish rebels. In September, when they landed in Kinsale, an English army quickly attacked them. Irish efforts to relieve their allies failed, and the Spanish returned home. O’Donnell surrendered shortly afterward, while O’Neill returned to Ulster, fighting all the way, but defeat was inevitable. On March 30,1603, he formally submitted to Mountjoy, the queen’s deputy, six days after her death. O’Neill’s submission was a fatal blow to Gaelic Ireland and jeopardized Catholic Ireland.

The Tudor/Stuart Plantation of Ireland

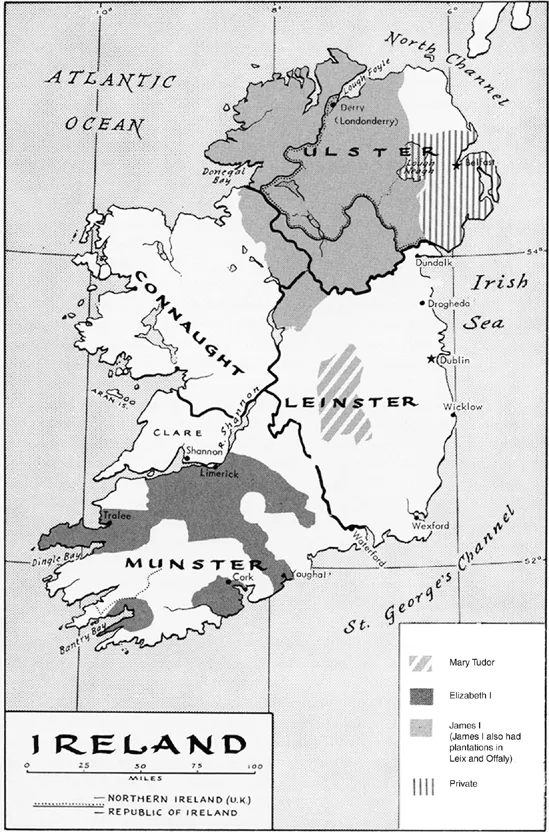

During the reign of Henry VIII, Lord Leonard Grey, representing him in Ireland, advised the king that the best way to secure English authority there would be to confiscate rebel property and transfer it to supporters of the crown. Catholic Mary Tudor (1553–1558) was the first monarch to employ plantation as a strategy. She seized O’Moore’s land in Leix and O’Connor’s in Offaly, shired and renamed them King’s and Queen’s Counties, and gave them to Anglo-Irish lords friendly to English interests, setting a precedent for territory in and out of the Pale.

In subduing Munster, Elizabeth awarded large estates to English adventurers in the royal army. She also shired Connacht and Ulster (Munster and Leinster were previously reorganized), creating present-day county borders. Under the new arrangement, authorities, particularly from 1606 to 1608, abolished Irish customs and institutions, replacing Brehon with common law.

In the wake of O’Neill’s surrender, James I (1603–1625), the first Stuart king, permitted him and O’Donnell to retain their properties and titles as earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell. But in 1607, fearing an English conspiracy to murder them, both chiefs fled to the continent, and in the end both died in Rome. The flight of the earls provided James with an opportunity to further pacify and control Gaelic Ulster. Previous plantation in the south and west were superficial, only transferring ownership of large estate from rebels to loyalists while Catholics remained on the land. In Ulster, James employed a policy used by the Stuarts to humble Gaelic chiefs in the Scottish Highlands. In 1610, he seized O’Neill and O’Donnell territory, extending over most of present-day Armagh, Cavan, Derry, Donegal, Fermanagh, and Tyrone, planting them with complete Protestant colonies: landlords, tenants, tradesmen, artisans, and merchants. James invited Anglicans from England and Presbyterians from Scotland to settle in Ulster. The thoroughness and density of the Protestant Ulster plantations made that province unique.

Not all post-Reformation Catholics in Ireland were native to the soil. Most of the Old English colony retained the faith. Duel loyalties to pope and king placed them in a difficult and dangerous position, losing ground to a growing influence of New English who had acquired Irish estates through conquest and plantation. But they continued to think of themselves as culturally and politically English. After 1613 they became a minority faction in Ireland’s Parliament and were liable to heavy fines for fidelity to Rome. During the reigns of James and his son, Charles I (1625–1649), English governments, by insisting on religious conformity as a loyalty test, gradually weakened differences between Old English and Irish Catholic. From an English perspective they were both offensive “papists.”

Plantations

In 1641, taking advantage of an English civil war between king and Parliament, Old English and Irish joined forces in rebellion. By spring 1642, they controlled most of Ireland, except for Dublin, Cork City and large portions of the county, Drogheda, Carrickfergus, Belfast, Enniskillen, Coleraine, Derry, North Down, South Antrim, and parts of north Donegal. In October 1642, Catholic bishops, Old English leaders, and clan chiefs met in Kilkenny to establish a provisional government. The Confederation of Kilkenny announced a commitment to freedom of private conscience, a right to practice openly in the church of one’s choice, Ireland’s independence, and loyalty to the King. The saying Pro Deo, pro rege, pro patria Hibernia unanimis (For God, for king, for country—Ireland united) summed up these principles.

Unfortunately, unity between the Old English and Irish Catholics was too fragile to survive. The Old English still considered themselves more English than Irish. They were intensely loyal to the Stuart monarchy and fought to maintain their property and place in Ireland’s Parliament. Irish Catholics wanted a comprehensive revolution, one that would restore the Gaelic order. They never had a significant parliamentary role and already had lost most of their property. Giovanni Battista Rinuccini, papal legate, and James Butler, earl of Ormond, the king’s deputy, manipulated and increased Confederation conflicts. Rinnuccini encouraged the native Irish to serve as a sword of the Counter-Reformation; Butler attempted to lure the Old English into the Stuart camp in its war against Parliament.

Confederation disputes and Ormond and Rinuccini intrigues divided military strategy; inadequate weapons, short supplies, and inadequately trained soldiers prevented military success. Meanwhile, antagonism among Ormond, a pro-English Parliament, and Ulster Presbyterians divided English interests in Ireland and prevented victory. In 1649, before Ormond and Confederation leaders agreed on coalition, Oliver Cromwell had already triumphed over Charles I. He then proceeded to Ireland, and when he left in 1650 he had mostly broken Catholic resistance. Within two years his lieutenant, Henry Ireton, completed the task.

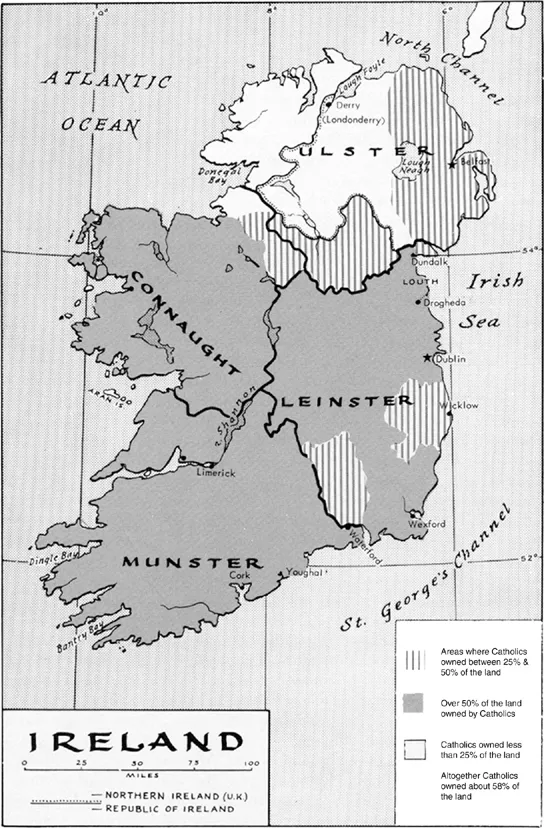

Massive confiscations and plantations followed Cromwell’s victory. Previously, despite Elizabethan and Stuart plantations, Catholics, mostly Old English, had managed to retain two-thirds of Irish property. Cromwell reduced that proportion to one-fourth. In addition to new plantations, war diminished the Catholic population by one-third. Some Catholics were transported to the West Indies in chains and put on the slave market. Others, including a large portion of the Catholic aristocracy and gentry, sought new homes in Connacht’s rugged and infertile terrain.

After the Stuart restoration (1660), Irish Catholics supported the monarchy in quarrels with England’s Parliament. They believed that Charles II (1660–1685) sympathized with their religious convictions and hoped that he would restore land that Cromwell had “stolen.” Charles did have a tolerance for things Catholic and returned a small amount of confiscated land. However, he had no intention of provoking British and Anglo-Irish hostile to the crown by repealing the Cromwellian settlement. His Catholic brother, James II (1685–1688), was openly friendly to Irish members of his faith. His Catholic deputy in Ireland, Richard Talbot, earl of Tyrconnell, found places for them in the Irish army and government.

Catholic Land Ownership, 1641

James’s pro-Irish Catholic attitude and conduct were factors, though not as important as the birth of a Catholic son and heir, in Parliament’s decision to depose him and invite his Protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch husband, William of Orange, to become England’s joint rulers (1650–1702). James abandoned England without a fight, deciding to make a stand in Ireland, where he had majority backing. War in Ireland between William and James fit into a wider European context as part of a conflict between Louis XIV of France and the Grand Alliance, a coalition of the Dutch, Hapsburgs, and some Italian and German forces that William led. The alliance attempted to frustrate Louis’s maneuvers to place a Bourbon on the Spanish throne and his territorial ambitions in the Rhenish Palatinate. With soldiers and money, Louis encouraged James to fight in Ireland as a strategy to occupy William’s attention and exhaust his resources. A dispute between Pope Alexander VIII and the French king concerning an opening for Cologne’s Archbishopric, and the Pope’s friendship with Holy Roman Emperor Leopold, meant that Rome endorsed the Grand Alliance and Protestant William against Catholic James.

On July 12, 1690, William’s army of 36,000 Englishmen, Irish Protestants, French Huguenots, Dutchmen, and Danes defeated James’s force of 25,000 Irish Catholics, supplemented with French officers on the banks of the Boyne, deciding the outcome of the war. James fled to France, leaving Irish Catholics to fight on against impossible odds. After William failed to take Limerick, defended by Patrick Sarsfield, he returned to England, leaving the campaign in the hands of trusted lieutenants. Before the end of 1690, the earl of Marlborough had conquered Cork and Kinsale.

Feuds and jealousies among its commanders weakened Stuart supporting Jacobite solidarity. When the war recommenced in 1691, little harmony existed between Tyrconnell, James’s leading lieutenant; the marquis de St. Ruth, Louis XIV’s representative; and Sarsfield, the Limerick hero. On June 30,1691, Godbert de Ginkel, one of William’s generals, prevailed over St. Ruth and took Athlone, opening the west for conquest. St. Ruth decided to defend access to Galway at Aughrim, near Ballinasloe in east Galway. He died there on July 12, demoralizing his soldiers, reversing the tide of battle in the midst of victory, and opening Galway to defeat and occupation on July 21. The remainder of the Irish army then retreated to Limerick. In August Tyrconnell died, of poisoning by enemies, according to rumors, but Sarsfield again managed to defend the c...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface to the Third Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Part I From Colony to Nation-State

- Part II From Free State to Republic

- Recommended Reading

- Index

- About the Authors