![]()

1

Cognitive theory of emotional disorders

Clinical psychology has been revolutionised by an influx of ideas and techniques derived from cognitive psychology and by the central metaphor that the mind functions as a processor of information. The basic assumption of the clinical application of cognitive theory has been expressed most economically by Ellis (1962). He suggests that emotional disorder is associated with irrational beliefs, particularly about the self. Irrational beliefs lead to both unpleasant emotions and ineffective, maladaptive behaviour. This theory expresses several hypotheses which have become widely accepted by clinicians working within the cognitive approach. First, beliefs have a causal effect on emotion and well-being. This hypothesis differentiates the cognitive approach from behaviourism. Second, beliefs, as causal agents, are expressed in verbal, propositional form, and can be accessed consciously during therapy. This hypothesis distinguishes the cognitive approach from most psychodynamic approaches, in which “latent” beliefs are unconscious. Third, therapy should be directed towards changing beliefs through restructuring cognitions, as in Ellis’ (1962) rational emotive therapy, in which the patient is taught to recognise and modify irrational, harmful self-beliefs.

The core assumptions of the cognitive approach just described are not in themselves sufficient to provide a workable model of emotional disorder. The most obvious difficulty is the resistance to change in irrational beliefs often encountered clinically. The person’s self-knowledge is not simply an internal “file” of disconnected beliefs which the therapist can erase and replace with more realistic propositions. People seem to construct and revise self-beliefs actively on the basis of some internal set of ground rules for interpreting the world. Emotionally disturbed patients may be characterised not so much by their specific beliefs as by the general frameworks they use to understand their environment and their place in it. In other words, clinicians must address the cognitive processes by which patients arrive at their maladaptive interpretation of the world. Another factor is the possibility of unconscious cognitive processing. Studies comparing introspective reports of processing with objective data have shown that people lack awareness of even some quite complex mental operations (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). A patient’s self-reports will provide only an incomplete and possibly distorted picture of their actual cognitive functioning. Psychopathology may be influenced by “automatic” processes, which may be more difficult to influence than conscious beliefs. In addition, people may fill the gap in conscious awareness by making attributions. The mind seems to abhor an informational vacuum, so, if we experience an emotion, we tend to search for an explanation, which may be incorrect. For example, Abramson, Seligman and Teasdale (1978) suggest that depressives are characterised by faulty attributions for negative events, tending to blame themselves rather than other agencies. Typically, the person is aware of the attributional belief, but not the unconscious and possibly automatic information processing which generates it. In practice, we may need quite a complex cognitive model, incorporating a variety of structures and processes (the “architecture” of the model), to provide a satisfactory basis for therapy.

Next, we consider Beck’s (1967; 1976; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Beck, Emery, & Greenberg, 1985) theory of emotional disorders, which offers perhaps the most influential and comprehensive account of cognitive processing in emotional disorders. This approach is based on constructs derived from experimental psychology, and is supported by evidence from both clinical observation and rigorous experiment. Our account will illustrate the need for differentiation of cognitive structures and processes, the role of the person’s active construction of a world-view, and the contribution of automatic processes, as just described.

Beck’s cognitive theory

Beck’s approach to emotional disorders is essentially a schema theory. It proposes that emotional disorders result from and are maintained by the activation of certain memory structures or schemas. Schemas consist of stored representations of past experience and represent generalisations which guide and organise experience. While individuals possess many different schemas, each one of which represents a different array of stimulus-response configurations, one of the most important schemas involved in psychopathology is the self-schema (e.g. Markus, 1977). This particular schema is used specifically to process information about the self.

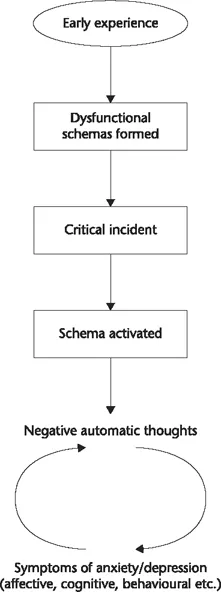

The basic tenet of Beck’s theory is that vulnerability to emotional disorders and the maintenance of such disorders is associated with the activation of underlying dysfunctional schemas. The activation of such schemas is accompanied by specific changes in information processing, which play a role in the development and maintenance of the affective, physiological and behavioural components of emotional disorders. These changes in processing are apparent as an increase in negative automatic thoughts in the stream of consciousness and as cognitive distortions or “thinking errors” in processing. These distortions take the form of biases or incorrect inferences in thinking, which we discuss in more detail later in this chapter. Beck’s approach is a tripartite conceptualisation which differentiates between three levels of cognition underlying emotional problems: the level of cognitive memory structures or schemas, cognitive processes termed thinking errors (Beck et al., 1979), and cognitive products, namely negative automatic thoughts. The basic cognitive model is depicted in Fig. 1.1.

Negative automatic thoughts

Each emotional disorder is characterised by a stream of involuntary and parallel negative “automatic thoughts” (Beck, 1967). In anxiety these thoughts concern themes of danger (Beck, 1976; Beck et al., 1985; Beck & Clark, 1988), whereas in depression thoughts about loss and failure predominate. The content of thought in depression has been referred to as the negative cognitive triad, which is dominated by a negative view of the self, the world and the future (Beck et al., 1979; Beck & Clark, 1988). In stress syndromes dominated by hostility, the content of automatic thoughts concern themes of restraint or assault (Beck, 1984). The “chaining” (Kovacs & Beck, 1978) of specific cognitive content to a disorder is the basis of the content specificity hypothesis in schema theory, which asserts that emotional disorders can be differentiated on the basis of cognitive content (e.g. Beck et al., 1987). Normal emotional reactions of anxiety and sadness are also associated with negative thoughts of danger and loss, etc., but in the emotional disorders there is a strong fixation on these themes.

FIGURE 1.1 Beck’s cognitive model of emotional disorders.

The term automatic thoughts was used by Beck (1967) to describe cognitive products in emotional disorders because they occur rapidly, are often in shorthand form, are plausible at the time of occurrence and the individual has limited control over them. The content of these thoughts mirrors the content of underlying schemas from which they are purported to arise.

Dysfunctional schemas

The underlying schemas of vulnerable individuals are hypothesised as more rigid, inflexible and concrete than the schemas of normal individuals. Dysfunctional schemas are considered to remain latent until activated in circumstances which resemble the circumstances under which they were formed. Their range of activation may generalise and this may lead to an increased loss of control over thinking (Kovacs & Beck, 1978).

Dysfunctional schemas have an idiosyncratic content derived from past learning experiences of the individual. There are at least two levels of knowledge represented in the dysfunctional schema which play a role in emotional distress (Beck, 1987): propositional information or assumptions, which are characterised by if–then statements (e.g. “If someone doesn’t like me I’m worthless”), and at the deepest level absolute concepts or “core beliefs”, which are not conditional (e.g. “I’m worthless”).

In anxiety disorders, the schemas contain assumptions and beliefs about danger to one’s personal domain (Beck et al., 1985) and of one’s reduced ability to cope. In generalised anxiety, for example, a variety of situations are appraised as dangerous and individuals have assumptions about their general inability to cope. In contrast, panic disorder patients tend to misinterpret bodily sensations as a sign of immediate catastrophe (Clark, 1986) and thus have assumptions about the dangerous nature of bodily responses. In the phobias, patients associate a situation or an object with danger and assume that certain calamities will occur when exposed to the phobic stimulus. Unfortunately, the paucity of research on the content of dysfunctional schemas in different anxiety disorders prevents firm conclusions about schema content in these disorders.

According to Beck et al. (1979), the depressed individual has a negative self-view, and the self is perceived as inadequate, defective or deprived and as a consequence the depressed patient believes that he or she is undesirable and worthless. The Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (Weissman & Beck, 1978) was developed to assess dysfunctional schemas in depression. The scale consists of a range of attitude clusters (e.g. “I can find happiness without being loved by another person”; “If others dislike you, you cannot be happy”; “My life is wasted unless I am a complete success”), and responses are made on a seven-point scale ranging from “disagree totally” to “agree totally”. The higher the overall score on the scale, the greater the level of dysfunctionality and proneness to depression.

Cognitive distortions

Once activated, dysfunctional schemas are thought to override the activity of more functional schemas. Although schema-based processing is economical, because individuals do not have to rely on all of the information present in stimulus configurations in order to interpret events, this type of processing sacrifices accuracy for economy of processing. A consequence of dysfunctional schema processing is the introduction of bias and distortion in cognition. These processes have been termed “thinking errors” by Beck et al. (1979) and are conceptualised as playing an important role in the maintenance of negative appraisals and distress. Specific errors have been identified:

• Arbitrary inference: Drawing a conclusion in the absence of sufficient evidence.

• Selective abstraction: Focusing on one aspect of a situation while ignoring more important features.

• Overgeneralisation: Applying a conclusion to a wide range of events when it is based on isolated incidents.

• Magnification and minimisation: Enlarging or reducing the importance of events.

• Personalisation: Relating external events to the self when there is no basis to do so.

• Dichotomous thinking: Evaluating experiences in all or nothing (black and white) terms.

Other cognitive distortions particularly prominent in anxiety are attention binding and catastrophising (Beck, 1976). The former is a preoccupation with danger and an involuntary focus on concepts related to danger and threat. Catastrophising involves dwelling on the worst possible outcome of a situation and overestimating the probability of its occurrence.

The role of behaviour in cognitive theory

Behavioural responses in emotional disorders can play a role in the maintenance of dysfunctional states. Phobic disorders are often accompanied by varying degrees of overt avoidance of feared situations. Aside from such gross avoidance, more subtle forms of avoidance also occur in anxiety disorders such as panic, agoraphobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The perception of danger in these disorders leads to attempts to avoid the threat. In panic disorder there is a misinterpretation of physical sensations or mental events as a sign of immediate catastrophe such as collapsing or going crazy. Following such cognitions, panickers may employ subtle avoidance or “safety behaviours” aimed at preventing the calamity (Salkovskis, 1991). For example, patients who believe that they are suffocating may attempt to take deep breaths and consciously control their breathing. Patients who believe that collapse is imminent may sit down, hold onto objects or stiffen their legs. Since the catastrophe does not actually occur, patients may then attribute its non-occurrence to having managed to save themselves. In this scenario, safety behaviours can have two effects which contribute to the maintenance of anxiety. First, particular safety behaviours may exacerbate bodily sensations. Deep breathing, for example, can lead to respiratory alkalosis and the range of symptoms associated with hyperventilation (dizziness, dissociation, numbness, etc.), and these sensations may then be misinterpreted as further evidence of an immediate calamity. Second, if panickers judge that they have managed to save themselves from disaster, their safety behaviours prevent disconfirmation of catastrophic beliefs concerning bodily sensations. It follows from this that manipulations which include a systematic analysis of safety behaviours and prevention of these behaviours during exposure tasks may increase treatment effects. Initial data from social phobics is consistent with this proposal (Wells et al., in press).

Behaviours aimed at controlling cognition can have a similar effect in preventing disconfirmation of beliefs concerning the dangerous nature of experiencing certain cognitive events. In addition, attempts to control or avoid unwanted thoughts may lead to a rebound of unwanted thoughts (e.g. Clark, Ball, & Pape, 1991; Wegner, Schneider, Carter, & White, 1987). This may be particularly relevant in the development of obsessional problems and problems marked by subjectively uncontrollable worry (Wells, 1994b), as discussed in Chapter 7. The application of safety behaviours relies on self-monitoring of bodily and cognitive reactions which are appraised as dangerous. This type of self-directed attention could have deleterious effects of intensifying internal reactions (see Chapter 9).

In depression, self-defeating and withdrawal behaviours can serve to maintain or strengthen dysfunctional beliefs. Depressive symptoms may be appraised as evidence of being ineffectual, which then leads to further passivity and hopelessness (Beck et al., 1979). Negative self-beliefs can give rise to self-defeating behaviours which reinforce these beliefs. For example, individuals who believe that they are unloveable may stay in abusive relationships because they negatively appraise their ability to form better relationships. Young (1990) terms such responses “schema processes”, which prevent disconfirmation of beliefs and maintain and exacerbate stressful life circumstances.

Cognitive model of panic

Clark (1986) developed a cognitive model of panic which has many overlapping features with Beck’s model of anxiety. In the model, panic attacks are considered to result from the misappraisal of internal events such as bodily sensations. Sensations are misinterpreted as a sign of an immediate impending disaster such as having a heart attack, suffocating or collapsing. The sensations most often misinterpreted are those associated with anxiety, although other sensations—for example, those associated with normal bodily deviations or low blood sugar—may also be misinterpreted. Similar misinterpretations are considered central in health anxiety (e.g. Warwick & Salkovskis, 1990), but in this latter disorder the app...