![]()

| PART

I | The foundations of the social cognition debate |

![]()

Introduction

I.1 What is ‘the social mind’?

What is special about human interactions? It is clear that our interactions with other people are quite different to those we have with rocks and trees and tennis balls. It’s also obvious that we interact with people in different ways depending on our relationship to them: our social exchanges with a stranger look and feel quite different from our interactions with close friends and relatives. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of our social interactions is that we see other people as having minds. This goes a long way towards explaining why we treat other people differently to rocks, trees, and tennis balls, which we generally do not think have minds. While there is more to our social lives than thinking about other people’s minds, it is certainly central to many of our interactions. One need only to walk into a café in the UK to overhear cheery gossip along the lines of ‘What was she thinking?’ or ‘He really thought she would like that?’ Bookshops have shelves of tomes advising us on ‘how to know your spouse’ or ‘understanding the teenage mind’. As we will see, although such chatter and fascination with the mind is not the norm across the globe, responding sensitively to other people’s thoughts certainly is.

This book is an introduction to the philosophy of social cognition. Among other topics it explores some of the steps researchers have taken to understand how we think about other people’s minds. What sorts of processes need to take place to allow us to see other people as minded? This in itself is a massive question, which can be examined from a variety of disciplinary perspectives. Neuroscientists look at the types of brain activity which seem to correlate with our attribution of minds to other people; developmental psychologists track the child’s understanding of other minds as she matures; clinical psychologists contribute insights from their work with adults who find it very difficult to attribute minds to other people; and anthropologists inform us about how attitudes towards knowledge of other minds vary across different cultures. As a philosopher, my role is to organise this array of insights to show how they support different theories about the processes underlying our ability to attribute minds to others. Most of the key theories have a clear philosophical heritage, stemming from mid-20th-century debates about Functionalism and computational theories of cognition. One of the aims of this book is to show you how these theories dominated early accounts of how we understand other minds, and how challenges to these accounts have shifted the direction of the social cognition debates.

The question ‘How do we think about other minds?’ is distinct from the question of ‘How do we know that other people have minds?’ The latter question is most closely associated with the philosopher John Stuart Mill, who wanted to know what epistemic justification we have for thinking that other people have minds:

(1865, p. 190)

Mill is pressing a sceptical question about whether we can know that anyone (besides ourselves) has a mind. It is a fascinating philosophical question, and the different methods philosophers have applied to resolve it are certainly worth looking at. However, the book sets aside this particular debate, focusing instead on a descriptive question – we know that ordinary adults treat other people as though they have minds, and we want to know how they are able to do that. What are the cognitive and social mechanisms which underpin our ability to think about other people’s minds?

I.2 Some terminology

While research in a highly interdisciplinary field like social cognition is truly exciting and rewarding, there are some pitfalls which arise when working across different disciplines. One of the most significant of these is terminology: many a conference argument has been calmed when the discussants realise, for example, that a philosopher’s understanding of the term ‘goal’ is different from the psychologist’s use of that concept. In this section of the chapter I stipulate how I am going to use certain key terms in the book. While I doubt there will be universal agreement on how I’ve done this, the aim is to reduce ambiguity as much as possible for the debates to come. A more comprehensive list of terms can be found in the Glossary.

I.2.1 Social cognition

‘Social cognition’ refers to our ability to interact socially with other people. It is the broadest umbrella term used in the book, and all the theories under discussion aim to elucidate some aspect of our social cognition.

I.2.2 Mindreading

Although ‘mindreading’ sounds like something one might encounter at the mystic’s tent at the county fair, it is intended to capture the much more pedestrian practice of how we think about other people’s minds when we are interacting with them. But, as Shaun Nichols and Stephen Stich point out, although we mindread on a daily basis, its familiarity should not detract from how amazing and complex this ability actually is:

(2003, p. 2)

There is more to social cognition than mindreading: as we will see, philosophers and psychologists have argued that some of our social interactions do not require us to think about other people’s minds at all. However, the focus of the social cognition literature in the past 30 years has focused on the phenomenon that is mindreading; and while not everyone takes mindreading to be synonymous with social cognition, there is a very broad consensus that there are social interactions that simply could not get started without some ability to think about another’s thoughts.

I.2.3 Psychological states/mental states

These terms refer to mental phenomena. Thoughts, hopes, judgements, preferences, moods, emotions are all examples of mental or psychological states. When we mindread, we are attributing psychological states to other people. ‘Mo is standing by the house’ does not reference anything psychological about Mo, just his physical status and location. ‘Mo is standing by the house, thinking about how to get in’ tells us something about Mo’s physical state and his mental state (that he is thinking about how to get into the house).

I.2.4 Propositional attitudes

Propositional attitudes are a type of psychological state. They have two parts: an attitude and content.1

Jess hopes that the shops will still be open.

Mo believes that it is sunny outside.

Asha imagines that Mars will be too hot to live on.

‘Hopes’, ‘believes’, and ‘imagines’ are each psychological attitudes that the subject (Jess, Mo, and Asha) has towards a proposition picked out by the emphasised words. And, of course, different people can have different attitudes towards the same proposition, as is the case when ‘Mo believes that it is sunny outside’ and ‘Jess hopes that it is sunny outside’ (propositional attitudes are discussed in more detail in Chapter 7).

The reason propositional attitudes are important is that, as we will see, much of the research into mindreading has focused on how we attribute them to other people and, more specifically, how we attribute beliefs – a type of propositional attitude – to other people. Chapters 1 and 2 will explain further why belief attribution has been so central in the mindreading literature.

I.2.5 Metarepresentational states

Metarepresentational states are thoughts we have about our own and other people’s thoughts. For example:

i. I think that I want to go to the party.

ii. [On seeing that there are no socks in the suitcase] I thought I had packed my socks.

iii. Jess hopes that Mo likes his present.

iv. Anne thinks that Sally believes the marble is in the basket.

v. They [Phoebe and Rachel] don’t know that we [Chandler and Monica] know they know we know.2

They are usually characterised as propositional attitudes, as the content of the agent’s (Jess, Anne) propositional attitude is another person’s (Mo, Sally) propositional attitude. They are metarepresentational states because the agent has a representational state (a hope or belief) about someone else’s representational state (Mo’s preference for the present, Sally’s belief that the marble is in the basket). In one’s own case, metarepresentation occurs when you are thinking about (usually evaluating) your own thoughts. For example, in (i) I am unsure if I want to go to the party or not, so I am thinking about what I want to do; and in (ii) I realise that a belief I held just a moment ago – that I had packed my socks – is actually false, and demands re-evaluation. Metarepresentational states have played a huge role in the mindreading literature, with researchers aiming to clarify how it is that we can have thoughts about our own and other people’s thoughts.

I.3 About this book

The book follows a mainly historical trajectory, beginning with landmark work in the late 1970s and ending up in the present day. However, it is a fast-moving field, and by the time the book has gone to press there will be more experimental data to challenge the theories discussed, and no doubt new theoretical developments as well. (Conversely, some of the newer findings discussed may turn out to be less robust than we currently think – see the Appendix for more details.) Despite the apparent imminent threat of obsolescence, I strongly believe it is helpful to take stock of the field to date, the twists and turns that it has taken, and, in so doing, gaining a better understanding of the future of social cognition research.

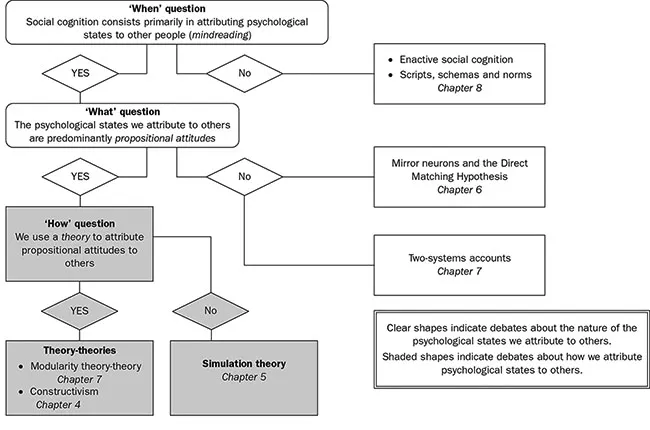

‘Mindreading’ is the main theme of this book. By showing how different accounts of mindreading have developed, I hope to elucidate why mindreading cannot be all that there is to social cognition. Three questions will recur throughout. When do we mindread? What counts as mindreading? How do we do it? (Figure 1).

I.3.1 Mindreading: when do we do it?

Humans engage in a multitude of social interactions. Here are some I have already encountered today:

i. discussing my intentions for the day with my husband, and planning when and what dinner will be;

ii. waving at my neighbour when I left the house;

iii. buying groceries at the supermarket;

iv. queuing for, and elbowing my way into, the lift at work; standing in the lift with six other people;

v. seeing that my colleague is trying to open the door but has her hands full, and holding the door for her.

This list is pretty average for a day in my life. I’m sure it’s also pretty average for most people I know. And yet, for each interaction, working out the best thing to do requires taking into account the needs and, in many cases, the thoughts of other people. I can do this more or less well depending on my relationship with the others involved: I can say with confidence that I know my husband better than I know the supermarket cashier; and while I interact with that cashier several times a week (or day, if I’m very disorganised), I didn’t recognise anyone who was taking the lift with me. The interactions were all very different, yet I somehow managed to negotiate them without (to my knowledge) causing offence.

A central question in the social cognition debate is how often we have to think about other people’s thoughts in order to successfully interact with them. Many Western philosophy texts seem to plump for the answer ‘nearly all the time’ (Antony, 2007; Nichols & Stich, 2003; see also collected papers in Carruthers & Smith, 1996). Psychologists have been more catholic in their approach, arguing that, while thinking about another person’s thoughts is certainly an important skill to have, there are alternative strategies to navigate social situations. These include social scripts, models, or schemas, which determine how one ought to behave in a certain situation (Apperly, 2010). For example, my supermarket schema says that I should pile my shopping onto the conveyor belt, pack my items after they have been scanned, listen to the amount uttered by the cashier, and provide some kind of payment for my goods. I’ve learned this schema from a lifetime of negotiating British supermarkets, first observing as my parents engaged in this schema and later participating in it myself. It’s not at all clear that in any part of the proceedings I need to think about what the cashier is thinking; in fact, it’s only when something goes wrong with the process that I am motivated to do so.

Throughout this book we will be examining different responses to the question of when we engage in mindreading. No one takes the view that we never engage in mindreading. But there is disagreement about whether mindreading is taking place for certain social phenomena. The disagreement pans out in two broad ways. First, there are situations, like the supermarket, where we can rely on scripts and schemas to navigate them, and such reliance does not reduce to mindreading. Second, there may be some phenomena where we think mindreading is occurr...