![]()

PART 1

The circles planning approach

The approach to medium-term planning used in this book is centred on a model provided by the Primary National Strategies (PNS). This model was taken from Eve Bearne’s excellently researched structure for planning as set out in the joint UKLA/PNS publication Raising Boys’ Achievements in Writing (2004). Longer, extended units of work are planned following a sequence of first reading, then planning, and finally writing:

Based on the work of Bearne (2002), the research recommended a structured sequence to planning where the children and teachers began by familiarising themselves with a text type, capturing ideas for their own writing followed by scaffolded writing experiences, resulting in independent written outcomes.

(Corbett 2008)

Not only does this approach allow teachers to see the big picture of a unit before they start teaching; it also enables them to plan a rich and impactful learning journey. Additionally, as the broad view of teaching is clear in the teacher’s head, he or she is better equipped to allow the unit to twist and turn according to the needs and interests of learners. The research findings in 2004 were:

… a three-week block was a new way of working, which was challenging but was seen to reap considerable benefit. For example:

… the slow build up to the writing objective really helped my young writers, particularly the boys who enjoyed the variety across time around one text.

… identifying specific long term intentions for each unit … enabled them to work more flexibly and creatively as they travelled towards these intentions and prompted them to listen to the children more acutely in the process. In focusing on the writing end product, they explicitly ‘built in more time to develop thinking and imagination’ and ‘planned for more time for the children to enact and perform’.

… a general sense of satisfaction in being able to cover short-term objectives within a longer time frame. Some felt that in the past, in trying to cover a range of short-term objectives, their work had been fragmented; they enjoyed what they perceived as increased flexibility to respond to the needs and interests of the children, whilst still being guided by the overall intention of the unit.

(UKLA/PNS 2004)

The strongest and most structured parts of my recommended model are the first two phases: the teaching and learning that builds up to the children drafting and shaping their writing. Once these parts are taught, the teacher will have a greater sense of how long he or she needs to give to the guided and supported part of ‘the final write’. If the groundwork has been laid, then the children will have firm foundations upon which to build – they will find the writing easier and more successful. The UKLA/PNS (2004) study called this ‘providing time to journey’; it found that:

A core issue emerged of a focus on less literal time allocated to writing, but more generative thinking time in the form of an extended enquiry through drama and visual approaches. This time was energetically spent in imaginative and engaging explorations of texts. Such time was significant as it allowed the teachers/practitioners to feel less hurried and to listen and learn more about individuals. It also meant that when the children did undertake writing they were unusually focused and sustained their commitment, persisting and completing their work.

The third phase of teaching and learning should also be mapped out so that the teacher has a sense of how the writing will progress over time. Two considerations may be whether they will ask the children to write in chunks, using teacher modelling to support as and when needed, or whether they will be drafting in one sitting and following it up with some redrafting over time. What we know is that providing space and time for children to develop a piece of writing leads to better quality writing:

Allowing time for the writing to develop and giving the learners space in which to develop their ideas and move slowly and gradually towards a final piece of writing … clearly influenced the quality of the final pieces and partly accounted for the raised standards in writing.

(UKLA/PNS 2004)

In most primary schools, there are long-term plans for literacy that record the coverage and content for each term of the year; there are medium-term plans that indicate the coverage and content for each block of work, or ‘unit’; and there are daily plans.

Each circles plan covers what has come to be known as a ‘unit’ of work. The timescale for coverage of the unit will depend on the amount of teaching and learning that needs to be done and on the pace at which pupils learn. For example, a poetry unit on creating shape poems may span five lessons, or a narrative unit on creating a spooky story may span 15 lessons. Broadly, before the unit starts, the teacher will have a sense of how many lessons it will take for the children to complete the journey through the phases of learning; however, there must be flexibility so that parts of the journey are repeated or skipped, in response to pupil need.

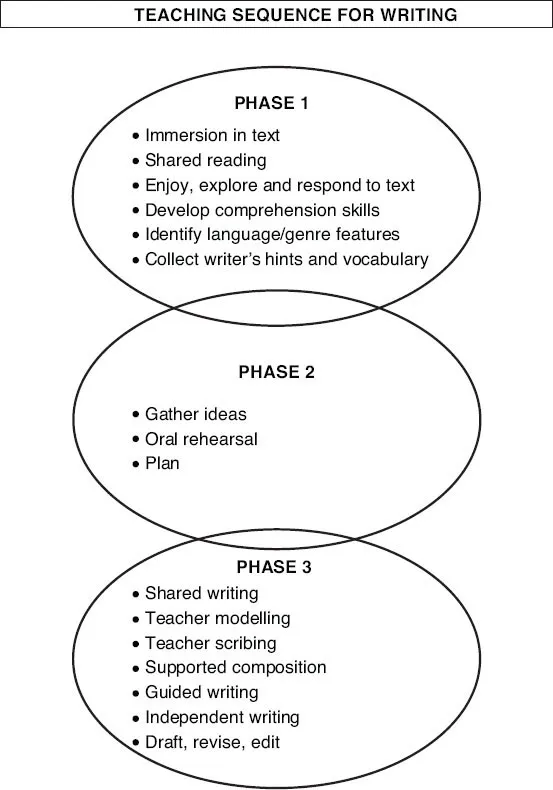

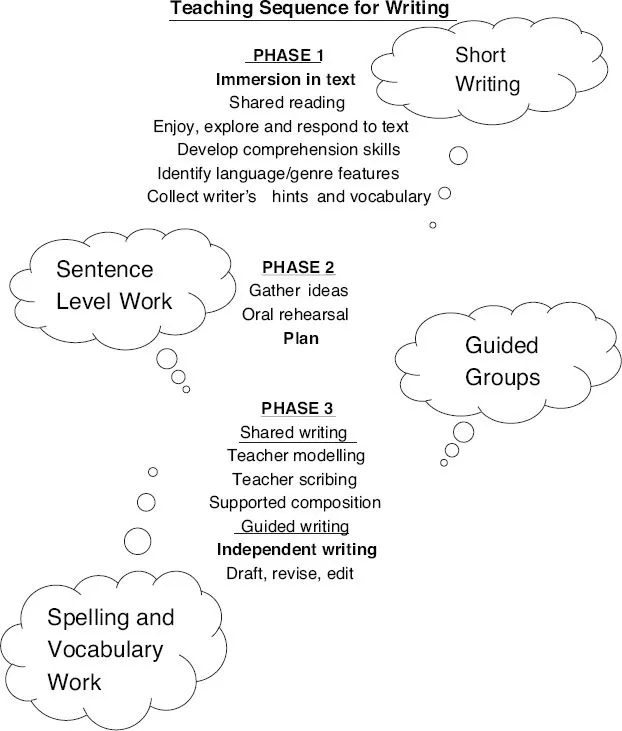

The circles plan is made up of three phases. Each phase plays an equal and vital part in building up to a final written outcome. Progression through the phases should feel like a journey for both pupils and teachers – a teaching journey for teachers and a learning journey for pupils. The journey should have twists and turns, there may even be diversions and delays, but the process itself should be enriching and engaging, and the final outcome, the destination, truly fulfilling.

The purpose of phase 1 is for the pupils to be immersed in text – the text type that they will eventually be authors of. The final outcome of phase 1 should always be that pupils know ‘what a good one looks like’ (WAGOLL) and, in many cases, ‘sounds like’ too. Phase 2 is the time for pupils to think about, plan, orally rehearse and play with their ideas for writing. And phase 3 is the writing phase. The journey begins at reading and ends with writing. This process is also known as (and rooted in) the ‘teaching sequence for writing’.

We have already established that the teaching sequence for writing has three phases that are discrete yet linked, which is why it is presented as a Venn diagram (see page xiv). We also know that the sequence is a map that guides teaching through a journey, of which the final destination is a piece of writing. The sequence is just that – a guide – it is the big picture of a unit of work; it should not be followed to the letter (the detail of teaching will be in the daily planning), but flex in response to pupils’ learning. Equally, there are no timescales attached to the sequence. Some units may take a week of lessons to deliver; others may take three weeks.

Phase 1: immersion in text type

AIM OF PHASE 1: TO KNOW WHAT A GOOD ONE LOOKS AND SOUNDS LIKE

A simple fact that cannot be argued with is that it is very difficult to write a particular text type if you are not familiar with it. Familiarisation with the text type is the first step, by the end of phase 1 children should be so immersed in it that they could write it if they had to. In The Really Useful Literacy Book, Martin et al. (2004: 39–41) say that:

writers have to have read the text type they are trying to write or have it read to them … From the experience of being read to and then wide reading, the writer builds ideas of what a successful piece of writing looks and sounds like … Children need to read and read and read – in order to both absorb the structures, sentence constructions and vocabulary of written texts …

Immersion is done through shared reading, when the teacher acts as a model reader making overt what good readers do by, for example, paying attention to the punctuation, using expression and intonation to aid understanding and bring the text alive, and asking him or herself questions and predicting. Pupils should always be able to see and follow the text during shared reading.

Shared reading is an opportunity to examine the purpose and audience of text, as this will be very useful when pupils begin to write their own: ‘if we add together purpose and audience (why am I writing and who will be reading it?) we find ourselves considering the best ways to construct the text we want to write’ (Martin et al. 2004: 34).

In addition to, and during, shared reading, the text should be brought alive so that children engage with it, understand it and respond to it as readers. It is really important that children are given opportunities to explore their responses to text; as children engage in ‘booktalk’, an expression coined by Aidan Chambers in his Tell Me approach (1993), they are experiencing being the audience – understanding how it feels to make sense of, and respond emotionally to, what they are reading. The purpose of this, within the teaching sequence for writing, is to help writers to begin to consider what response they may want to elicit in the reader. You can’t truly write for an audience unless you’ve walked in the footsteps of the audience.

As well as eliciting reader response, immersion in the text enables children to hear and collect vocabulary and language patterns, internalise plot structures and deepen their understanding. At this point in phase 1, the children should be supported to gather vocabulary that they like and think they will utilise in their writing.

Equally, rather than the teacher giving the children a list of elements that feature in a text type, they should be collecting them as they read and engage in the text type. During phase 1, children should be given opportunities to collect, in addition to vocabulary, ideas and authorial effects to be used, later, in their own compositions. These lists are sometimes referred to as ‘success criteria’ or similar; however, it is my belief that the more child-friendly, less threatening, labels such as ‘writer’s hints’ make more sense to children, and therefore are more likely to be used when they write. These lists can be used as checklists during or after writing, but they should always be displayed, perhaps on a ‘working wall’, during the unit.

Booktalk and close analysis of the text, this time focusing on how the writer has achieved effects on the reader, and being supported to understand what the writer has done to elicit this response and have that effect, are also key parts of phase 1 of the teaching sequence. These ideas should be added to the ‘writer’s hints’ list mentioned above.

Phase 2: gathering ideas and shaping them into a plan

AIM OF PHASE 2: TO HAVE PLANNED MY WRITING

In order to be ready to compose a text, we need to have collected ideas, played with them, decided on the best ones and then shaped them into some form of a plan. This is what phase 2 is for.

Initially, experimentation is the key – children should be freed up so that the ideas flow. They should be encouraged to share ideas, identify what might work, play with vocabulary and language so that they can find the best way to express themselves, and orally rehearse. All of these methods involve talk. Ros Fisher et al. (2010: 39) state that ‘talk will help them think up and extend their ideas but also … help them to gain a better understanding of the writing task set by the teacher’. She explores using talk to generate ideas through role-play, drawing on experience, using pictures and artefacts, and telling others.

In his Talk for Writing approach, Pie Corbett (2008: 6–7) suggests the use of:

• Writer-talk games … to develop and focus aspects of ideas and language for writing

• Word and language games to stimulate the imagination and develop vocabulary and the use of language

• Role play and drama to explore ideas, themes and aspects of the developing writing

Once children have had opportunities to talk through their ideas, they should then be shaped into a plan. This may be a story map, mountain or a storyboard, a series of boxes or a skeleton. It is my opinion that schools should have set planning pro forma so that pupils become familiar with the format; I also believe that planning format...