eBook - ePub

Western Civilization: A Global and Comparative Approach

Volume I: To 1715

- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Featuring the one author, one voice approach, this text is ideal for instructors who do not wish to neglect the importance of non-Western perspectives on the study of the past. The book is a brief, affordable presentation providing a coherent examination of the past from ancient times to the present. Religion, everyday life, and transforming moments are the three themes employed to help make the past interesting, intelligible, and relevant to contemporary society.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Western Civilization: A Global and Comparative Approach by Kenneth L. Campbell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

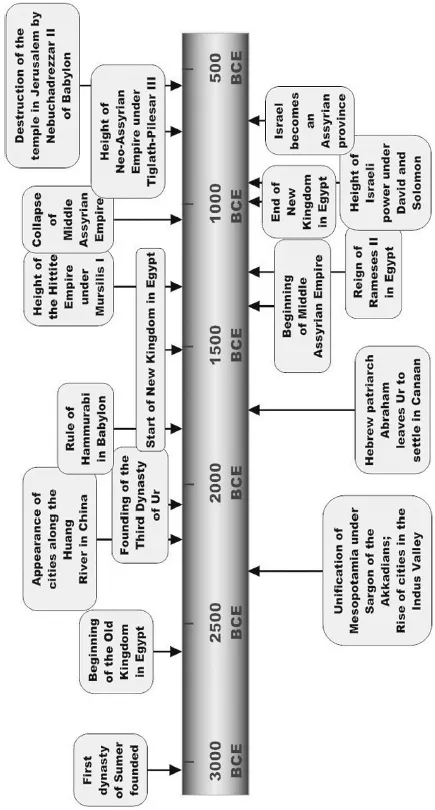

| The Beginnings of History and the ancient near east |

The story of Western civilization did not begin during the Italian Renaissance, the Middle Ages, or even with the classical cultures of Greece and Rome. Human history—at least as far back as we can possibly trace—exists on a continuum in which human beings always learned something from their predecessors. Developments, ideas, and inventions from many hundreds or thousands of years earlier influence what human beings are doing at any given moment in their history. Climate and geography play a role, too—and these have been known to change over the course of time as well. There are reasons why the first civilizations emerged where and when they did, just as there are reasons why Western civilization would emerge where and when it did. The larger context of Western civilization demands at least some consideration of the history that preceded it.

What we know about human origins and the prehistoric past is part of the history of humanity that provides that larger context for Western civilization. We can trace the existence of art, religion, magic, and the attempt to understand the natural environment deep into the prehistoric period. The transition to settled agriculture made possible many later historical developments, but was itself a gradual process that was part of the continuum of history. In fact, even after the rise of the first urban civilizations and well into recorded history, the vast majority of the people made their livings from agriculture. The complex and detailed histories of the first ancient civilizations are only briefly discussed here, but with an emphasis upon the main course of their history, their basic characteristics, and their relationship to one another. The Sumerians and Babylonians, the Egyptians and the Hebrews all made their contributions to the legacy of the ancient world that later influenced and shaped Western civilization. But they also deserve attention in their own right for the vital role that they played in the emerging human experience.

Human Origins and Prehistory

A series of startling discoveries in the twentieth century raised as many questions as they provided answers about the distant origins of human beings. Still, we know much more than we did 100 years ago, and new evidence continues to increase our knowledge and understanding. The pioneers in this field were the British husband-and-wife team of Louis (1903–1972) and Mary (1913–1996) Leakey. Their discoveries of early human-like remains in Kenya and Tanzania, including fossils and footprints that dated to approximately 3.7 million years ago—combined with the discovery of a 1.6-million-year-old skeleton of the species Homo erectus by their son Richard—helped to establish Africa as the site of the origins of humanity. These discoveries were reinforced by two finds in Ethiopia, the first a 3.25-million-year-old female skeleton given the name of Lucy, found by a University of Chicago-trained paleoanthropologist named Donald Johanson (b. 1943). The second was the discovery in 2006 of a more complete skeleton and skull of a three-year-old child of the same species as Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis). At some point representatives of the species Homo erectus, which walked upright and more closely resembled modern humans than the earlier Australopithecus, migrated from Africa, as evidenced by the earliest discovery of the species in 1890 on the island of Java in Indonesia by a Dutch paleontologist, Eugène Dubois (1858–1940). The discovery of additional remains of Homo erectus in China and more recently in 1991 in Georgia in central Asia indicate a great expansion of hominids about 1.3 million years ago, perhaps as a result of a dietary change toward increased meat-eating that led them to expand their habitat. The first appearance of humans in Europe has now been dated to about 780,000 years ago, which is much earlier than paleontologists had previously thought.

Given the long periods during which these human ancestors inhabited the earth, the appearance of the more recognizably human Homo sapiens and Neanderthals occurred relatively recently, within the past 150,000 to 200,000 years. The Neanderthals, named after the Neanderthal valley in North-Rhine Westphalia, Germany, where their remains were first discovered in 1856, were long thought to be the ancestors of modern humans, but are now considered a separate and distinct line of humanity, sharing only a distant ancestor with their Homo sapiens cousins. Neanderthals, known for their large bones, sloping foreheads, and short limbs, were capable of a wide range of human skills, activities, thoughts, emotions, and communication, although not through verbal language as we know it. They had brains equal in size to those of contemporary humans and, if they worked differently, they worked successfully enough for them to survive and flourish for 170,000 years, much longer than our current species, Homo sapiens sapiens, has been in existence. What most distinguished the line of human beings from which we descend was the use of language, a greater ability to innovate and adapt new technologies that were more effective at manipulating the environment, and a capacity for abstract thought, although Neanderthals did believe in an afterlife and buried their dead. The novelist Jean Auel (b. 1936) has provided a fascinating and speculative look at the possible relationship between Neanderthals—who died out around 30,000 years ago—and Homo sapiens sapiens in her Earth’s Children series.

During the Paleolithic period, otherwise known as the Stone Age, prehistoric humans developed certain types of tools that defined their culture, including mainly knives, scrapers, and related instruments for shaping, cutting, polishing, grinding, and making notches. These same basic tools, usually made of flint, served humans for millions of years until a noticeable shift late in the Paleolithic period—the so-called Upper Paleolithic, around 40,000 years ago—to new tools made of animal materials such as bones, antlers, or ivory. It is difficult to say whether humans changed because of these innovations or if they made these innovations because they had changed. Steven Mithen (1996) has suggested that the human brain actually underwent significant changes during this period that allowed it to better integrate knowledge of the natural world with technological skills. In addition to the creation of new tools, which included hunting weapons such as spear-throwers made from antlers, bevel-pointed flint tools known as burins, and small geometrically shaped tools known as microliths, the people of this period also demonstrated great creativity in the splendid artworks that have survived from it. Paleoanthropolo-gists have placed the origins of human art between 75,000 and 91,000 years ago, with the 2007 discovery in Morocco of painted shells used as beads for a bracelet or necklace now considered to be the oldest known example. By the time of the Upper Paleolithic, jewelry made of animal teeth or stones and other examples of bodily ornamentation were fairly common, but it was the beginnings of cave painting around 30,000 years ago that marked the most spectacular artistic development of this transitional period. Using flint knives and paint made from clay, artists produced images of bison, deer, lions, bears, horses, and woolly rhinoceroses in caves in southeastern France discovered in 1994 by Jean-Marie Chauvet, which supplemented earlier finds at Lascaux Cave near Montignac in the southwest of France and at Altamira in northern Spain.

One thing that all prehistoric people had in common was that they lived in a society of hunter-gatherers. They traveled wherever necessary to find food. These migrations were made more necessary, at least on the European continent, by the last Ice Age, which did not begin to thaw until around 10,000 BCE. The art of the period between 20,000 and 10,000 BCE, which includes the caves at Lascaux and Altamira, reflects a strong preoccupation with the sacred dimensions of the hunt but also—in the form of smaller bone-carvings and the like—with signs of spring that were so eagerly awaited every year. These foragers lived off the land and depended heavily on available resources; their societies could only be as large as the land would sustain. This meant that for the most part their groups remained small, leading to a particular type of social organization that was clan-based. Coastal regions might sustain a slightly larger population because of the ability to supplement their food supply from the sea, although the groups who lived in these regions practiced hunting and gathering as well. But populations seem to have been getting larger, beginning as early as 30,000 BCE, which made necessary greater levels of cooperation and adaptation within and even among these groups. At some point they began to supplement their diet by deliberately planting and cultivating a portion of their food supply, leading to a gradual shift in human social and economic organization that produced perhaps the greatest single change in human history: the agricultural revolution.

The Shaping of the Past: The Agricultural Revolution

The transition from a hunger-gatherer society to a society based on settled agriculture was a gradual process; it did not occur as a result of a single breakthrough in one place, or even several. If this transition occurred in a number of places in the period from roughly 10,000 to 5000 bce, this was largely because of a change in environmental conditions that made settled agriculture advantageous, especially for feeding the expanded populations of particular regions. But archaeological evidence suggests that other factors were involved that made the process less deterministic than a simple environmental explanation would indicate. Furthermore, the gradual and extremely slow pace of the transition indicates that a dichotomy of hunter-gatherers versus settled agriculturalists is far too simplistic. Many hunter-gatherer societies made some use of the deliberate cultivation of food-producing plants long before 9000 BCE, the date by which grain-based agriculture had taken root in southeast and southwest Asia. In addition, long after settled agriculture had become established in places such as the valley where the Huang River makes a huge bend in northern China, agricultural societies continued to supplement their food supply by practicing traditional hunting and gathering techniques.

It makes sense that hunters and gatherers near advantageous sites for grain agriculture—which also included the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys in southwest Asia and the Indus River valley in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent—would first experiment with settled agriculture in close proximity to the woodlands that provided traditional food sources from foraging. But this does not preclude the use of agricultural techniques for food production by numerous other hunters and gatherers, even in places that did not yield the later spectacular successes of river valleys such as that of the Nile in Egypt. In other words, the agricultural revolution did not occur simply because the climate improved at the end of the last Ice Age, leading to larger, more settled populations that were more likely to create a stable food supply by turning to the cultivation of grains—though this could easily have been one factor. Rather, it occurred as the result of a large number of individual decisions that occurred at different times in different places and for a variety of reasons, some of them perhaps unique to particular societies—such as the creation of a sanctuary at Göbecki Tepe in Turkey by hunter-gatherers who needed to provide for all the people that would have been drawn to it.

Whatever its origins, agriculture brought many other changes to human society. First, the cultivation of more food and the existence of a more predictable supply would have encouraged further population growth. In addition, the greater availability of food encouraged the construction of more permanent buildings near agricultural sites, the making of pottery and utensils for storing and consuming the food, and systems of mathematics and writing for recording and tracking transactions involving large amounts of grain. Social organization seems to have been affected as well. Societies became less collectivized wholes with a common food supply and more divided into individual family units with separate residences, as archaeologists have confirmed from buildings dating to 8000 BCE found at the town of Jericho on the lower Jordan River.

As populations increased in the regions where agriculture was most successful, these societies began to expand into other regions still populated by hunter-gatherers. This does not mean that the main agricultural centers were solely responsible for the spread of agriculture, which, as previously stated, hunter-gatherers proved perfectly capable of discovering on their own, as they did in many places. Nor does it mean that agriculturalists either displaced or converted hunter-gatherers to their way of life. Populations in places such as the Greek mainland or along the Danube River in Europe were so sparse throughout the first several millennia after the agricultural revolution had begun that farmers and hunter-gatherers could have lived independently within the same region, much as Neanderthals and Homo sapiens once had. Still, expansion of peoples had its effects, especially after about 4000 BCE when such influences can be more easily traced. Knowledge of crops, domestication of animals such as sheep and goats, and technological innovations such as the ox-drawn wooden plow (invented around 5000 BCE) would have provided great advantages and do seem to have spread from southwest Asia to Europe during this period. Languages spread along with the people who spoke them, affecting the evolution of language throughout Europe, Asia, and northern Africa. The one main agricultural center that remained relatively isolated—northern China—only very gradually received influences from the Indus valley and central As...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Dedication1

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables, Maps, and Charts

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: The Beginnings of History and the Ancient Near East

- Chapter 2: Greece and the Mediterranean World, ca. 2000–350 BCE

- Chapter 3: The Hellenistic Age and the Rise of Rome, ca. 350–30 BCE

- Chapter 4: The Roman Empire and the Enduring Legacy of the Ancient World, ca. 30 BCE–500 CE

- Chapter 5: Early Christian Europe, Byzantium, and the Rise of Islam, ca. 410–750

- Chapter 6: The Shaping of Medieval Europe, ca. 750–1100

- Chapter 7: The High Middle Ages, ca. 1000–1300

- Chapter 8: The Crises of the Late Middle Ages, ca. 1300–1500

- Chapter 9: The Renaissance, ca. 1350–1517

- Chapter 10: The Beginnings of European Expansion, ca. 1400–1540

- Chapter 11: The Protestant and Catholic Reformations

- Chapter 12: The Age of European Expansion, ca. 1550–1650

- Chapter 13: Absolutism and Political Revolution in the Seventeenth Century

- Chapter 14: The Scientific Revolution and Changes in Thought and Society in the Seventeenth Century

- Epilogue: The Shaping of the Past and the Challenge of the Future

- Index

- About the Author