![]()

Introduction

In recent years, it has become a commonplace in educational psychology that knowledge is constructed by learners, rather than being simply transmitted to them by their teachers. The implications of this viewpoint for the educational process are revolutionary, because it shifts the traditional focus of authority, responsibility and control in the educational process away from the teacher and towards the learner. Attaining competence in a professional domain means acquiring the expertise and thus the authority to make professional decisions; assuming responsibility for one’s actions; and achieving autonomy to follow a path of lifelong learning. This is empowerment.

Many different ways of looking at the knowledge-construction process have been proposed, some of them more cognitive, focusing on what goes on in one person’s mind, and others more social, seeing knowledge construction as a collaborative, interpersonal activity. From an information-processing perspective, for example, knowledge construction is viewed essentially as an individual, cognitive process:

What is needed to comprehend a text is not solely contained in the linguistic and logical information coded in that text. Rather, comprehension involves the construction of meaning: The text is a preliminary blueprint for constructing an understanding. The information contained in the text must be combined with information outside of the text, including most prominently the prior knowledge of the learner, to form a complete and adequate representation of the text’s meaning. (Spiro et al. 1992:64)

This cognitive psychology approach, focused on what is allegedly going on in the individual’s mind, has been the focus of a considerable amount of attention in translation studies over the past ten years, particularly in work based on think-aloud experimental methods, as in Krings (1986, 1992), Lörscher (1991), Hönig (1990), Jääskeläinen and Tirkkonen-Condit (1991) and Kiraly (1995). While working on the research that culminated in Pathways to Translation, I was drawn, at least partially, into the mindset of the cognitivist approach to translation studies that was emerging in the mid-1980s. Then, as now, I depicted translation in terms of a double bind: as an internal, cognitive process and as an external, social phenomenon. Yet, in analysing the think-aloud protocols produced by novice and expert translators while they performed translation tasks, I was working under the implicit assumption that by having subjects verbalize what they were thinking while translating, it would be possible to identify cognitive strategies as if they were fixed routines, artefacts of the mind that could be extracted, dissected and perhaps even distributed to translators-in-training.

Since completing that earlier work, my understanding has evolved to a point where I see this cognitive science approach to translation processes as epistemologi-cally incompatible with a social process perspective. The former rests on the assumption that meaning and knowledge are products of the individual mind – replicable, transferable, independent of social interaction and essentially static – while the latter assumes that they are dynamic intersubjective processes.

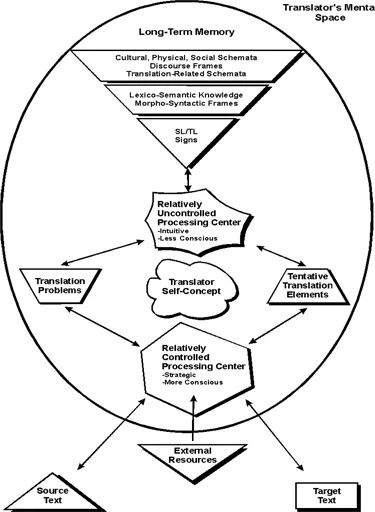

A critique of my own earlier depiction of mental translation processes (see figure 1) will perhaps best explain my shift in perspective away from a cognitivist view and toward a social constructivist one.

Figure 1: A cognitive processing model of translation

Underlying this model is essentially an information-processing view of the mind. Information of different types is seen to be ‘stored’ in long-term memory and outside resources. The translator is depicted as an independent cognizing agent who ‘retrieves’ data from various sources as needed and as a function of his or her translation strategies, which are conceived as blueprints or plans for cognitive action to solve problems. The black boxes inside the translator’s mind – both of which are depicted as receptacles – are respectively portrayed as the conscious and unconscious sites of information processing. The uncontrolled processing centre is an essentially unconscious workplace in the mind where intuitions bounce through the receptacle containing retrieved information; it intuitively produces tentative translation elements and identifies translation problems that are then processed strategically and more consciously in the controlled processing centre. The translator’s self-concept is shown as a cloud hovering in the background of intuitive and cognitive activity. This self-concept is the psychological identity that the translator creates through learning and experience with translation activities, the individual’s understanding of him- or herself as a translational information processor.

From such a perspective, the translator’s knowledge and strategies could be seen as existing apart from actual translational interaction. Moving logically from this image of the underlying cognitive processes involved in translation, it is but a small and tempting step to use this concept to justify a transmissionist approach to the teaching of knowledge and skills. In addition to teaching comparative syntax and encouraging rote memorisation of pairs of bilingual lexical items and idiomatic expressions, we could also justify the teaching of the ‘right’ strategies. Teachers could retain their traditional function of transferring knowledge, expanded to include the procedural knowledge of how to produce correct translations. From this perspective, it should be unnecessary to implicate learners in the actual give-and-take of multi-faceted negotiation that characterizes translation as a social process. There is nothing in the model that reflects my current belief that the development of true expertise can only be developed on the basis of authentic situated action, the collaborative construction of knowledge, and personal experience.

I first became uncomfortable with the cognitivist approach when I confronted my finding in Pathways to Translation that intuitions (which I defined as non-strategic, relatively uncontrolled, and virtually untraceable mental processes) appeared to be deeply and inextricably involved in the mental processes I was trying to observe. Intuitions do not fit neatly into a ‘scientific’ cognitivist perspective precisely because, buried as they seem to be in the dark recesses of the mind’s black box, they leave nothing but the most ephemeral traces of their links to more conscious, strategic processes. We cannot readily identify their origins, we cannot predict under what circumstances they will emerge, and we cannot ‘teach’ them.

From a social constructivist perspective, intuitions are dynamically constructed impressions distilled from countless occurrences of action and interaction with the world and from the myriad dialogues that we engage in as we go about life in the various communities of which we are members. By communicating and negotiating with peers and more experienced (and thus more knowledgeable) others, we acquire a feel for correctness, appropriateness and accuracy, a feel that is grounded in our social experiences, and bound up in the language we use and share with other people. This is the place where the present volume departs from the path I took in Pathways to Translation. Rather than taking a new fork in the road, I have retraced my steps, moving back to the position derived from my early experiences with language teaching (to be discussed in Chapter 9), and the acknowledgement that, as knowledge is intersubjectively constructed, learning must be socially situated.

A constructivism for translation studies

From a social constructivist perspective, individuals have no choice but to create or construct meanings and knowledge through participation in the interpersonal, inter-subjective interaction that the philosopher Richard Rorty has called the “conversation of mankind” (Rorty 1979). While our personal meanings and understandings of the world can never be identical to those of any other individual due to the idiosyncratic nature of experience, language serves as a common denominator of interpretation that makes it possible for communication to take place at all. As children become acculturated, they acquire and use language to make sense of the world through the sociolinguistic glasses of the communities they are in the process of joining. Subsequent learning can thus be seen as a type of re-acculturation, as a process of becoming increasingly proficient at thinking, acting and communicating in ways that are shared by the particular knowledge communities of which we are striving to become members.

The implications of these epistemological premises for the translator education classroom are far-reaching. They include the need for a radical re-assessment of teachers’ and students’ roles in the classroom, a new perspective on the function and nature of testing, and a reorientation of the very goals and techniques of the educational programme. It is important to note that constructivism is not directly related to the school of literary theory called deconstruction, although I am sure that parallels could be drawn. In fact, in another publication (Kiraly 1998), I identified an affinity between the pedagogical implications of constructivism and those of deconstruction drawn by Arrojo (1994) concerning the learning of translation skills through collaboration in an authentic setting. Arrojo is one of the few contemporary translation studies scholars to promote the reorganization of the conventional, teacher-centred classroom into a forum for authentic and interactive learning. I have chosen not to draw deconstruction further into the discussion at this point, but the investigation of the links between these approaches would, however, be an interesting topic for further research.

This book is not intended as a didactic cookbook with ready-made lesson plans and off-the-shelf classroom procedures that can be applied directly to other translation studies classrooms. From a constructivist viewpoint, the ideas presented here, as in all acts of communication, cannot be ‘objective’ in the conventional sense, corresponding to reality or truth. They are ineluctably coloured by each individual’s personal and idiosyncratic interpretations of the principles, events and examples portrayed. While I am describing a teaching method here, it is my own personal method, which will, by necessity and by design, differ in its applications from programme to programme and from teacher to teacher.

Towards a comprehensive teaching method: approach, design and procedures

I would like to clarify my understanding of the concept of teaching ‘method’ right from the start, by drawing on the framework proposed by Richards and Rodgers (1986) for analyzing instructional systems in the field of foreign language teaching. Their depiction of a teaching method as comprising the three elements of approach, design and procedures seems particularly well suited to understanding the educational framework to be discussed here.

An approach comprises a theory of language and a theory of language learning that serve as the foundation for the principles and practices implemented in a method. From this perspective, the approach is clearly the most fundamental level of a method. It relates to a view of the world and of learning, teaching and language use that can transcend individual teaching and learning environments and the limits of individual institutions. At the other end of the spectrum we find procedures, which include “classroom techniques, practices and behaviour observed when the method is used” (Richards and Rodgers 1986:20).

It is at the procedural end of the spectrum that we find the greatest degree of diversity and variability, at the level where teachers, working collaboratively and individually, implement a theoretical approach in actual pedagogical practice. Design is the link between an approach and pedagogical procedures. In Richards and Rodger’s words:

Design is the level of method analysis in which we consider (a) what the objectives of a method are; (b) how language content is selected and organized within the method, that is, the syllabus model the method incorporates; (c)the types of learning tasks and teaching activities the method advocates; (d)the roles of learners; (e) the roles of teachers; (f) the role of instructional materials. (ibid.:20)

My task here is to outline a theoretical approach that I hope many teachers can share; to show how I have interpreted the implications of the approach for the design of the key features of classroom interaction; and to provide some examples and suggestions focused on the procedures I have developed for my own classroom practice. My overriding goal in dealing with all three aspects is to provide an impetus for further interpretation, elaboration and experimentation, which I hope will initiate a dialogue toward innovation for the empowerment of students of translation.

Sources of inspiration

The ideas presented in these pages are derived from my 15 years of experience as a translator educator at the School of Applied Linguistics and Cultural Studies of the University of Mainz in Germersheim, Germany. The initial experiences I had during my first few semesters, when I tried to appropriate the instructional performance techniques used by other teachers, made me decide either to work toward developing a systematic and humanistic approach to the training of translators, or to leave the institution.

Like most other translator educators, I had also received no special training in translation teaching methods prior to assuming my duties in Germersheim. I was encouraged to sit in on classes run by my colleagues and to pick up ideas on how to teach from them. This very practice, in lieu of any methods or programmes for the training of translator educators, is clearly a major reason why the instructional performance model is perpetuated from one generation of teachers to the next. There has been no forum for investigating the assumptions underlying this approach or possible alternatives to it.

There is a desperate need for comprehensive degree programmes for the training of translator trainers. This, I contend, could be a major first step out of the rut that our profession is in, a step toward the professionalization of translator education. We can start to educate generations of educators who know how to do classroom research, how to recognize and focus on the ever-evolving skills and knowledge that our graduates will need, and how to design classroom environments that lead to professional competence. If pursued with enthusiasm, creativity and the best interests of our students, of the profession, and of society as a whole in mind, these measures cannot help but radically improve the value and efficacy of our programmes as well as the status of the graduate translator.

Classroom research

My initial efforts to break out of the traditional, teacher-centred mould in my own classes culminated in my doctoral dissertation research, completed in 1990 at the University of Illinois, and published in 1995 under the title Pathways to Translation. One part of the study was a think-aloud-protocol investigation of the cognitive translation processes of novice and professional translators. The other part involved the development of initial steps toward a systematic approach to translator education. Pathways to Translation was an exploratory study that was meant more to raise questions than to answer them. Here, some tentative answers to those and other related questions will be presented. These are answers that have worked for my students, and that I hope will serve as examples for others. As I stated at the beginning of this chapter, my assumptions have evolved considerably since Pathways was completed, in particular due to my having become acquainted with the field of constructivist education that has been emerging for the past few decades, particularly in Anglo-Saxon countries. I was first introduced to constructivism through the excellent, collaboratively written volume Constructivism and the Technology of Instruction: a Conversation, edited by Thomas Duffy and David Jonassen (1992). I then went on to read scholars including von Glasersfeld (1988), Dewey (1938), Rorty (1979), Brown et al. (1989) and Vygotsky (1994). The more I read, the more I realized that my personal theories of foreign language learning and translator education can best be articulated from a social constructivist perspective. The approach to translator education outlined here owes a particular debt to Collaborative Learning by Kenneth Bruffee (1995), which convinced me of the viability of a consistently non-foundational, social constructivist perspective. Bruffee says that learning, “is not ‘a shift inside the person which now suits him to enter … new relationships’ with reality and with other people. It is a shift in a person’s relations with others, period” (Bruffee 1995:74).

Quintessentially, this view holds that meaning, knowledge, and the mind itself are inextricably embedded in our personal interactions with other people. This helps explain and justify the move in this book away from the dual cognitive-social perspective to translator competence and translator education I adopted in Pathways to Translation. As I will explain further in Chapter 2, I now believe that the social, inter-subjective nature of meaning, thought and mind provide a much more coherent framework for the elaboration of an approach to translator education than a two-track, cognitive/social approach. I have come to reject the dualistic distinction of the internal workings of the mind as being something essentially different f...