![]()

Part 1

Approaching Southeast Asian development

![]()

1

Approaching Southeast Asian development

Andrew McGregor, Lisa Law and Fiona Miller

Introduction

Southeast Asia is typically presented as a development success story. Since the collapse of colonialism most countries have experienced significant improvements in health, education, incomes and opportunities, and boast swelling middle classes. The region has avoided inter-state conflict for an extended period under the auspices of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and while many political freedoms remain restricted, at a regional scale progress in countries like Myanmar and Indonesia suggest they have been improving. The infrastructure and facilities of cities like Singapore and Bangkok have made them globally significant finance and transportation hubs, and the region continues to attract high levels of foreign investment, bolstered by initiatives such as the recent formation of the ASEAN Economic Community. Improvements in agricultural production alongside enhanced mobility have diversified rural incomes and opportunities, while initiatives oriented at conserving the region’s rich natural resources and biodiversity have proliferated. There are many challenges ahead, particularly in terms of positioning itself alongside the neighboring political economies of India and China; however, the future of the region is generally considered to be bright.

Such glossy regional interpretations provide a narrative that is attractive to many, particularly political and business elites within and outside the region. However it is only part of the story. As countless studies have shown, Southeast Asia is a region of immense diversity, not only in terms of society, culture, economy, environment and politics, but also in terms of its development experiences. Southeast Asia has indeed developed at an impressive pace over the last few decades, but, as is well recognized, development has been uneven and comes with its own set of challenges and costs. More critical accounts highlight the huge disparities in wealth and opportunity dividing rich and poor, the millions of people left behind by development – even in ostensibly middle income countries, the lack of security or services typifying sprawling informal urban settlements and impoverished rural villages, the harsh labor conditions sustained by foreign investment in export processing zones, widespread human rights abuses and abuse of power, and the ongoing degradation of the natural environment to fuel primary industries and rampant consumption. These stories are also true, providing a counterpoint to narratives of success.

Given such diversity the challenge of putting together this Routledge Handbook of Southeast Asian Development is a considerable one. We could side with either inflection to provide an update on development from those perspectives – reinforcing one set of stories over the other. We have chosen not to do that. Instead we have invited a range of outstanding regional scholars to each provide a chapter analyzing an aspect of development that reflects cutting edge scholarship on the topic. In particular we asked authors to move beyond mere description or critique to identify the processes of development and how more equitable, sustainable and empowering forms of development might be pursued. In this sense the Handbook provides a level of understanding that goes far beyond the statistical analyses that dominate development reports on the region. Such statistics are important but fall well short of capturing how and why development is occurring and what the intended and unintended impacts may be. Instead we have sought to provide a perspective on development in the region that goes beyond statistics and simplistic good/bad binaries from the multiple viewpoints of those who have spent their careers studying it.

In taking on the task of analyzing Southeast Asian development, two sets of issues immediately become apparent. First, what is Southeast Asia and how and why should we approach it as a region. Second, what is development and how should we approach it in the Southeast Asian context. In what follows we will build from previous scholarship on these topics to argue that a regional approach to development is important for understanding how and why development occurs in some places and not others. Our intention is not to smooth out the uneven experience of development across the region – a regional GDP does not feature! – but instead to highlight the interconnections that are bringing about diverse development geographies. The regional scale, existing between the nation-state and the global, is under-represented in academia and practice, and yet it reveals much about the nature of development and its variable impacts.

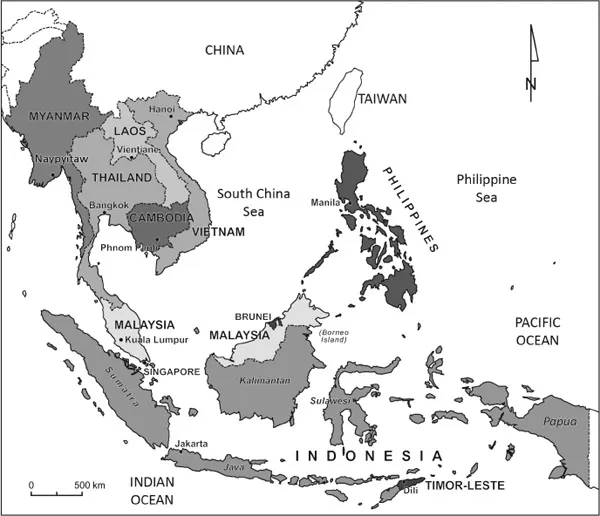

Southeast Asia as a region

The region examined in this collection incorporates what is sometimes known as mainland Southeast Asia – Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos), the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, Malaysia and Singapore – as well as maritime or insular Southeast Asia comprised of the Philippines, Indonesia, Brunei Darussalam and Timor-Leste (see Figure 1.1). The grouping is driven by geography: the region is nestled between China and India to the north and northwest, the Pacific and Indian oceans to the east and west, and Papua New Guinea and Australia in the southeast. However, the borders of the region, or where the region ends, have been driven as much by colonialism, nationalism and geopolitics as any essential geographic feature. The indigenous people of Papua, for example, in Indonesia’s easternmost province, have much more in common with their Melanesian cousins in Papua New Guinea on the eastern side of the island than people in Java, or broader Southeast Asia. Similarly ongoing unresolved tensions concerning the large gas deposits beneath the Timor Sea involving Australia, Indonesia and Timor-Leste, or in regards to the natural resources and geopolitically vital sea routes of the South China Sea involving claimants from Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan and China, prevent firm maritime boundaries from being drawn at all.

These lingering boundary disputes reflect a longer lineage of uncertainty regarding the very existence of an identifiable region. Such uncertainty is structured around a dialectic of unity and diversity. On the one hand the region defined as Southeast Asia is seen as a space of shared cultures; on the other the diversity of the region is readily apparent and gives it a distinctive quality. Unity is identified in social and cultural traits that are shared widely across the region, some of which are thought to have derived from long patterns of internal and external trade, and others from patterns of wet and dry rice cultivation linked with the tropical monsoon climate (Gillogy and Adams 2011, 5). Milton Osborne (2004), for example, argues that women and the nuclear family are generally more valued in the region than in neighboring states and much has been made of a traditional mandala political structure, in which pre-colonial kingdoms set up tributary systems that had no set territorial boundaries but faded in influence with distance from the core. The selective appropriation of Indian and Chinese influences, evident in, for example, the absence of India’s caste system, also suggest particular cultural norms and values are shared across the region. The extensive Chinese diaspora throughout the region is another common feature across many societies. In contrast diversity within the region is also very apparent. No other world region boasts the same degree of geographic, religious, linguistic, cultural, ethnic, economic, ecological and political difference.

Figure 1.1 Map of Southeast Asia

Historically, the region has been framed in part by its position in relation to two larger neighbors. Indians referred to it as Suwarnadwipa (Goldland) and the Chinese Nanyang (South Seas). Arab traders knew it as Jawa, and the Europeans as Further India. Within the region empires rose and fell, such as the Angkor kingdom centered in current day Cambodia, Pagan in Myanmar, and Chinese vassal state of Srivijaya that controlled east-west trade to China from current day Indonesia and Malaysia. A consolidated regional power structure equivalent to India or China failed to form; instead existing divisions were accentuated during an extended colonial period when Portugal, Spain, Britain, France, the Netherlands and the United States established colonial boundaries that continue to mark the extent of state territories. However even then the concept of a distinct region had yet to develop, and it wasn’t until the 1890s that German language scholarship first referred to the term Southeast Asia (Siidostasien) in a purely geographical way (Reid 2015, 414). The term caught on and became more widely used, particularly during the Second World War and the subsequent Cold War when the region was of critical geopolitical importance. These external signifiers were formally internalized through the formation of ASEAN in 1967 when a Western-oriented alliance of Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines formed amidst the turmoil of the Vietnam/USA War. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the cessation for the Cold War eventually saw a broadening of ASEAN to include all states of the region with the exception of Timor-Leste – the region’s newest country – which has applied for membership and is expected to be admitted soon.

Southeast Asian imaginaries now proliferate through maps, tourism, media and geopolitical strategies; however, it is unlikely that a strong Southeast Asian identity has swept through the diverse populations that make up the region. Different ways of imagining and dividing the region help illustrate this point. Timor-Leste, for example, despite sharing half of its island with the Indonesian province of West Timor, has observer status on the Pacific Island Forum – the main political grouping of Pacific Island countries – and has joined the Pacific Island Development Forum, forging links with similarly small island states. Other groupings such as East Asia, Asia Pacific, Pacific Rim, Indochina, Australasia, Oceania and Western Pacific, provide alternative ways of grouping and dividing the states of Southeast Asia. More challenging is Willem van Schendel’s (2002) naming of Zomia to refer to the Tibeto-Burman language areas occupied by highland groups stretching from Vietnam, Laos, Thailand and Myanmar through Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Bhutan and China, occupying spaces conventionally divided between Southeast, East, South and, more recently, Central Asia. Concepts like Zomia call into question the self-evident nature of the regions that currently comprise the world in geographical maps, including Southeast Asia, and open possibilities for alternative research trajectories as evident in James Scott’s (2009) subsequent anarchist history of the area.

Alternative regional imaginaries also highlight the problems of searching for particular traits at the regional scale – as presumably different traits would be found if different regional groupings, such as Zomia, were used. The once prominent Asian Values argument, for example, has faltered, in part, due to the sheer diversity of values inherent in Asian societies and the difficulties in even defining what or where Asia is. This does not mean that Malaysians and Indonesians don’t share similar traits – clearly they do – but it is harder to identify the traits shared by middle class Chinese residents of Singapore, the Kachin people living in the mountains on the China-Myanmar border and the post-disaster rural fishing communities of Indonesia’s Aceh. Similarly colonial empires have left cultural marks in the languages and institutions that link geographically diverse nations, such as Portugal, Timor-Leste and Angola, or Malaysia, Britain and India – creating imaginary post-colonial geographies that could equally be the focus of a book such as this.

Despite these possibilities it is the Southeast Asian regional identity that has stuck to become the dominant self-reinforcing geopolitical and cultural frame. Given its diversity and somewhat arbitrary boundaries and definition we approach the region not as a space of shared endemic traits but as a dynamic region that is continually forming and reforming in response to internal and external processes. We see value in Appadurai’s (2000, 7) conception of process geographies, whereby attention is directed toward movement rather than stability, and regions are recast as “problematic heuristic devices for the study of global geographic and cultural processes.” Our attention, in focusing on development, turns to what Anna Tsing refers to as the ‘friction’ of global encounters, how globalizing processes are engaged with, transformed and grounded in particular geographic spaces, often with unexpected outcomes. The study of such flows challenges homogenous and static images of regions, which are instead creatively likened to lattices, archipelagos, hollow rings and patchworks (Van Schendel 2002). Regions matter, not because of shared norms and values, although where they exist these are important, but because of the social, economic, political and biophysical interconnections that cross national boundaries, underpin regional formations and shape encounters with external and internal processes.

Development in Southeast Asia

We approach development in a similar way. Rather than focusing on a core indicator or trait, such as GDP, human rights or freedom, we borrow again from Appadurai (2000) to see development as comprising a set of flows characterized by what he calls relations of disjuncture. Development is far from a smooth and seamless project, instead the speed, impacts and forms of development differ spatially and temporally, between and within regions, states, sectors, cities, villages and households. There is no one development; instead there are a myriad of ideas and resources that have become associated with this powerful but slippery concept. Certainly, as post-development researchers have argued, development is about change and because of that it necessarily disrupts, and can destroy, what existed before. Disjunctures are created through the unevenness of these disruptions, whereby improved access to markets, technology, healthcare or education emerge unequally across time, space and society, reflecting the unpredictable friction of place-based encounters. Some benefit from development interventions while others are disadvantaged, or as Rigg (2015, 4) has observed more subtly “problems and tensions that have arisen from growth.” For this reason we do not take a normative perspective on whether development is good or bad (contrast almost any pro-growth report from the World Bank with Wolfgang Sach’s 2010 Development Dictionary), as its goodness or badness depends on time, space, perspective, culture, power relations and the materialities of particular initiatives. Perhaps most important is the capacity of those most affected to selectively engage with development and actively steer development processes toward desirable ends. A role for researchers is to highlight the injustices and inequalities that emerge, thereby making space for alternative approaches, when this is not the case.

In applying this lens to development in Southeast Asia we are interested in dynamism and diversity, seeking to understand how people and places are engaging with the globalizing forces of development. We do not pursue a regional economic development model (see Hill’s 2014 review and dismissal of the idea), but we are interested in how the incorporation of countries into the region influences their development. Space and scale matter to development, and a regional optic can provide insights into processes that national, local and global analyses cannot. As James Sidaway (2013, 997) writes in relation to Area Studies, “It is imperative, however, to supplement historical and history with geographic and geogr...