![]()

1 Paley Park, New York

(4,200 square feet / 390 square metres)

INTRODUCTION

Paley Park was completed in 1967 and completely rebuilt to the same design in 1999. Privately owned, privately built and privately run for free public use, it is the model ‘vest pocket park’. Located on the north side of East 53rd Street in midtown Manhattan, between Fifth Avenue and Madison Avenue, Paley Park is the product of a concept promoted by landscape architect Robert Zion (1921–2000) and taken up by William S. Paley (1901–90). Paley, founder and Chairman of the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), established the park as a memorial to his father, Samuel Paley (1875–1963). It was not a result of ‘Incentive Zoning’, a policy commenced in 1961 that permitted developers ‘to install paving around their buildings, call them plazas, and collect their 10:1 or 6:1 floor area bonus as of right’ (Kayden 2000: 18). Paley Park was a philanthropic donation to the people of New York. Few human-made places provoke such unequivocal praise – ‘one of Manhattan’s treasures, a masterpiece of urbanity and grace … memorable because it makes no effort to be so’ (Johnson 1991: 191, 194); ‘visiting Paley Park affects me as much as going to Yosemite’ (Kim 1999: 88); and again, ‘a restrained and effective multisensory experience’ (Kim 2013: 79).

HISTORY

Date and reason for designation as a park

The concept of the pocket park was demonstrated by Zion in May 1963 at an exhibition, New York Parks for New York, organized by the Park Association of New York and staged at the Architectural League of New York. He showed prototypical designs for parks ‘as small as 50 by 100 feet [15 by 30 metres] between buildings where workers and shoppers could sit and find a moment’s rest’ (Tamulevich 1991: 7). The sites that Zion used were vacant lots on 40th, 52nd and 56th Streets. Such proposals caused controversy between their advocates, Mayor John Lindsay (1921–2000 – Mayor 1966–73) and his Park Commissioners Thomas Hoving and August Heckscher, on the one hand, and Robert Moses, New York park commissioner from 1934 to 1960, on the other. Moses argued that open spaces of less than 3 acres (1.2 hectares) would be ‘very expensive and impossible to administer’ (Seymour 1969: 5).

Paley would have been aware of the exhibition and of the controversy surrounding pocket parks. In a statement issued shortly after the opening of the park in May 1967, he stated that ‘as a New Yorker, I have long been convinced that, in the midst of all this building, we ought to set aside occasional spots of open space where our residents and visitors can sit and enjoy themselves as they pause in their day’s activities. When I was casting about for an appropriate way to create a memorial to my father … it occurred to me that to provide one such area in the very center of our greatest city would be the kind of memorial that would have pleased him most’ (Paley – undated). Paley formed the Greenpark Foundation in 1965 to acquire a site close to CBS headquarters and build the park. Construction began on 1 February 1966. The park opened on 23 May 1967.

Size and condition of site at time of designation

The site had been occupied from 1929 to 1965 by the Stork Club – ‘one of New York’s most legendary nightspots’ (Lynn and Morrone 2013: 241). It is 42 feet wide by 100 feet deep (12.8 by 30.5 metres). In line with the Manhattan street grid, it is oriented to the southwest – optimal for sun pockets. Although the sidewalk in front of the park belongs to the City of New York, it is a visual extension of the park.

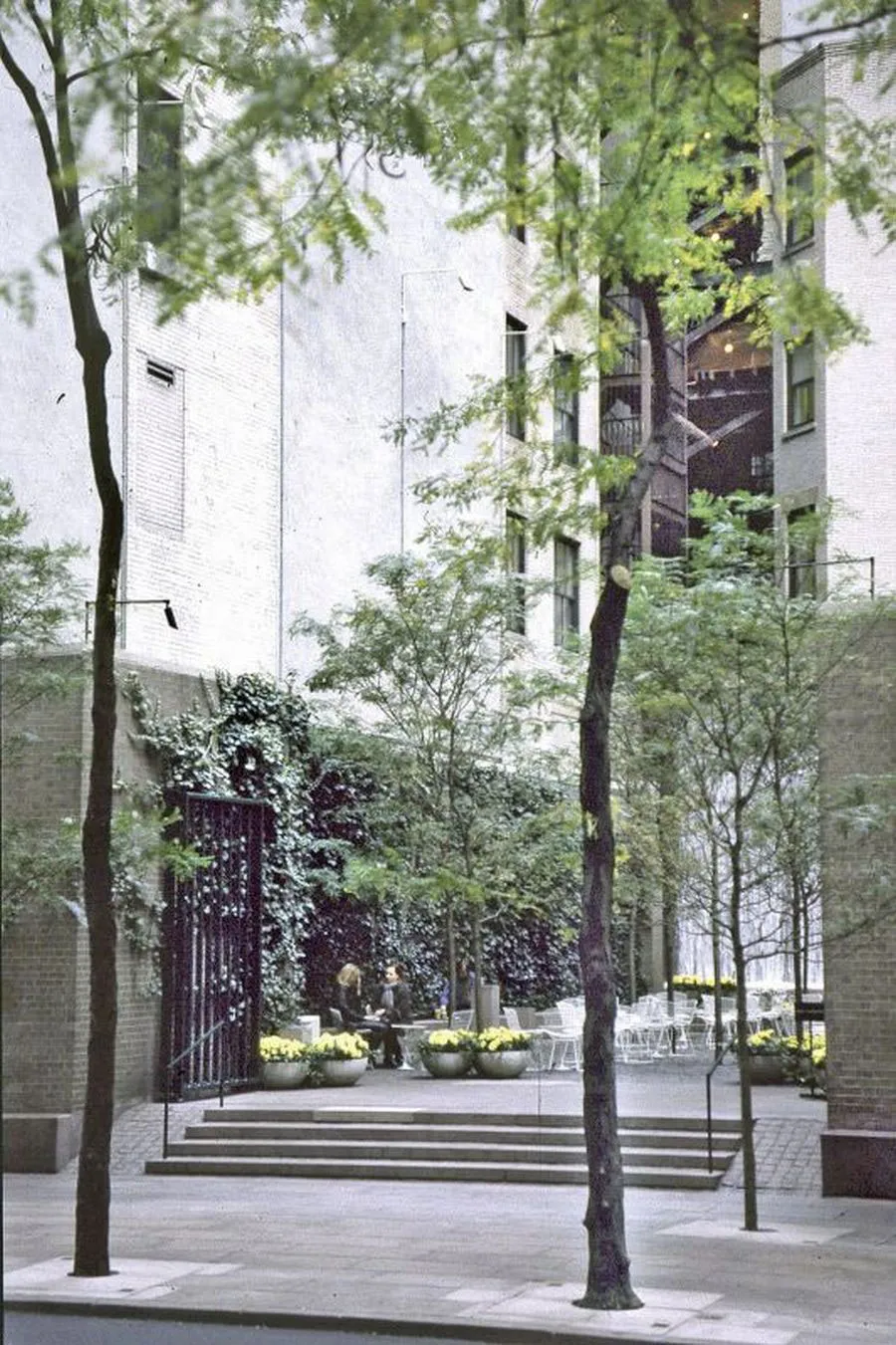

Entrance from 53rd Street (October 1999)

Twenty-foot/6-metre-high waterfall (November 2011)

Key figures in the establishment of the park

Paley’s father was a Russian immigrant who became a successful cigar merchant. Paley joined his father’s company after graduating from Wharton School of Finance at the University of Pennsylvania. He developed an interest in broadcasting after buying advertising time on a Philadelphia radio station. Described as ‘fabulously wealthy and notoriously despotic’, Paley had an uncanny ability to succeed with projects that others treated more cautiously. This led him, first, to buy an unprofitable chain of radio stations and, later, to invest in TV broadcasting ‘when skeptics were denouncing the new medium’. He was ‘an intensely private man with patrician tastes’ (Macleans Magazine 1990: 58).

Robert Zion obtained masters’ degrees in business and in landscape architecture from Harvard. In 1957 he went into business with fellow Harvard-trained landscape architect, Harold Breen. Zion’s marketing included writing letters to newspaper and magazine editors about the firm’s work and an article in the AIA Journal about ways to make New York City more habitable – including gallerias, parklets and zoolets – ideas that were eventually presented at the Architectural League exhibition in 1963 (Decker 1991: 22). Zion was, by all accounts, as demanding a person as Paley.

PLANNING AND DESIGN

Location

Paley Park is located ‘in the midst of one of the most congested and frenetic parts of midtown Manhattan’ (Lynn and Morrone 2013: 240) – a concentrated area of stores, offices and hotels, just the other side of Fifth Avenue from the perennially popular Museum of Modern Art.

Original design concept

The concept demonstrated at the 1963 exhibition showed a prototype ‘based on the concept of a small outdoor room … with walls, floors and a ceiling’ (Zion 1969: 75). It dealt with size – as small as 50 by 100 feet; enclosure – removed from the flow of traffic and sheltered from noise; purpose – for adults to rest; furniture – movable, comfortable, individual seats; materials – rugged; walls – neighbouring buildings, covered with vines; floor – with textural interest and pattern; ceiling – dense canopy from trees 12 to 15 feet apart; waterworks – bold and simple; kiosks – with vending machines or cafés (ibid: 76). ‘Food’, as William H. (Holly) Whyte noted, ‘draws people, and they draw more people’ (Whyte 1980: 53).

Tables and chairs in half of park during building works on other half (May 2013)

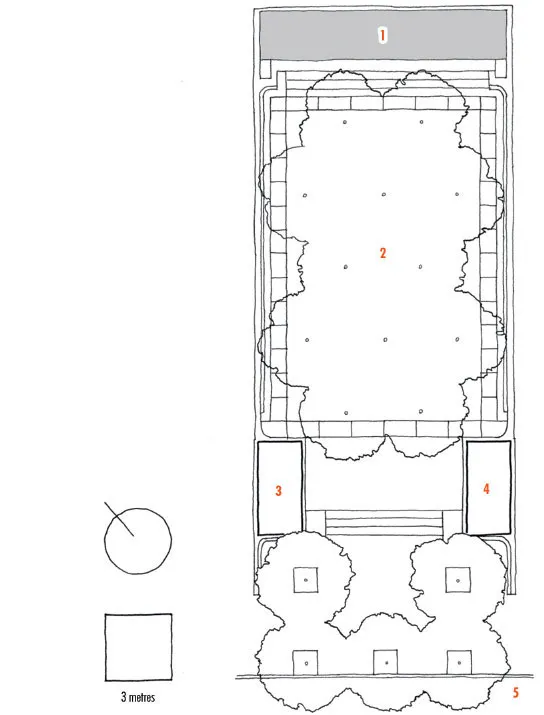

Paley Park, New York

1 Waterfall

2 Honey Locust Grove

3 Gatehouse/Pump Room

4 Gatehouse/Kiosk

5 East 53rd Street

Layout and materials

The trees in Paley Park – honey locusts – were planted in a 12-foot (3.6 metre) quincunx rather than the square grid shown in the 1963 exhibition. This looser layout, their continuation onto the sidewalk and the long, low steps at the entrance all contribute to the ordered casualness in the park. The shelter from surrounding buildings and the orientation create a comfortable micro-climate, allowing sunshine at lunchtime from spring to fall.1 But the single most alluring feature in Paley Park is the 20-foot-high (6 metre) waterfall that thunders down the full width of the back wall at the rate of 1,800 gallons (6,800 litres) a minute. The loud but somehow soothing roar dulls the sounds of the surrounding city. The steps, outer paving and planter walls are stippled pink granite – smooth but not too slick. The central paving is 4-inch (100 millimetre) red-brown granite setts in a square grid – controlled but not too stiff. The sixty movable, white Bertoia-designed wire chairs and twenty white marble-topped tables add to the sense of informality. The mono-specific tree planting and ivy on the walls complement the almost Zen-like restraint of the hard materials. The year-round cycle of herbaceous plants includes yellow tulips each spring.2

The renovation in 1999 included replacement of the waterfall pumps and of the underground irrigation system; replacement of all soils and planting (apart from the three honey locusts in the City-owned sidewalk); lifting, cleaning and reinstallation of all hard materials, and replacement of all site furniture. The granite setts were re-used, bedded on concrete and grouted-in, incorporating grilles around the trees.3 The original cost of the park, including land acquisition, was around $1 million. The renovation cost around $700,000.

Paley Park and 53rd Street from above (October 1999)

MANAGEMENT AND USAGE

Paley Park is owned by the Greenpark Foundation and funded by an endowment established under Paley’s will. In 2013 the park had three on-site staff. There is virtually no vandalism beyond the occasional theft of flowers. In its early years it was noted that ‘since its opening, between 2,000 and 3,000’ people visited the park ‘every sunny day’ (Birnie 1969: 173). Whyte recorded in 1980 that ‘the two places people cite as the most pleasing, least crowded in New York – Paley Park and Greenacre Park – are by far and away the most heavily used per square foot’ (Whyte 1980: 73). He recorded thrity-five people per 1,000 square feet in Paley Park and concluded that sensitive design increases the carrying capacity of small urban spaces. The current capacity is set at 200 people at any one time. The heaviest use is between 11:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. The park is open twelve hours a day seven days a week but closed on Thanksgiving, Christmas and Independence Day, and for the month of February – a change in 2014 from the previous practice of closing the park for the month of January.4 The intention is for the park to remain exactly as it was originally designed.

CONCLUSIONS

Subtle and sophisticated, Paley Park is a carefully conceived retreat from the bustle of midtown Manhattan. Its Zen-like restraint creates an ideal contrast with its hyper-urban setting. It is an object lesson in the use of orientation to create optimal micro-climate, use of flexible seating to accommodate dense crowds, use of white noise to obscure street noise, the attraction of outdoor food outlets in urban locations, and the value of human surveillance. The scale and function of Paley Park are a specific response to Manhattan conditions. Its impact has been as potent in its own way as the impact of Central Park.

NOTES

1 Jacobs (1961: 103–6) argued that enclosure, intricacy, centring and sun are the principal requirements for the success of neighbourhood parks.

2 Noted at meeting with Phillip A. Raspe Jr. of the Greenpark Foundation on 24 April 2000 that yellow tulips form part of cycle because, at the time of opening, Paley’s wife, Barbara Cushing Paley, requested that they always be displayed in spring.

3 Noted at meeting with Patrick Gallagher of the Greenpark Foundation on 20 May 2013.

4 Noted at meeting with Patrick Gallagher of the Greenpark Foundation on 20 May 2013.

![]()

2 Village of Yorkville Park, Toronto

(0.36 hectares / 0.9 acres)

INTRODUCTION

The Village of Yorkville Park lies just north and one block west of the iconic intersection of Toronto’s two major streets – Yonge and Bloor. It occupies a 150-metre by 30-metre...