![]()

Part 1

About Flexible Formworks

Graphite drawing by Mark West

![]()

Chapter 1

On Flexibility

It may be noted that although reinforced concrete has been used for over a hundred years and with increasing interest during the last decades, few of its properties and potentialities have been fully exploited so far. Apart from the unconquerable inertia of our own minds, which do not seem to be able to adopt freely any new ideas, the main cause of this delay is a trivial technicality: the need to prepare wooden forms.

Pier Luigi Nervi (extract from Structures, F.W. Dodge, USA, 1956, p, 95)

Control

Concrete has next to no opinion about its shape; a wet, heavy, gloppy material, it will take any shape you give it, so long as you can hold it still for a few hours (Schjeldahl 1992). Its plasticity suggests that it might take an extraordinary variety of forms so how did such an amorphous material end up as so many rectangular solids and cylinders?

The origins of the right angle, and its ubiquity in the realm of human affairs, holds a deep and complex story. The following little story only touches the surface, but it will do.

Nearly all industrial building materials are produced through some form of simple mill – saw mill, rolling mill, extrusion, etc. These are all single-axis mills, whether powered by wind, water, animal, or engine.1 Whatever passes through such a mill will have a uniform section along its length. This is the instrumental origin of all the straight, flat sticks and sheets that constitute our building materials. Obvious exceptions include things that are carved or cast. But if you are casting into a mould made of sheets and sticks, then the casting will likely be both flat, straight and built with 90-degree joints. A rectangular box, after all, is the easiest thing to make from flat, uniform-section stock.

Developed in parallel with single-axis production mills are engineering calculation techniques that rely on the analysis of (flat) sectional areas. The slide rule, which developed alongside structural theory and its calculation methods, is an analog computer that can multiply (or divide) only two numbers at a time, and as such was particularly suited to calculating the area of rectangles and uniform-section volumes. This combined and coherent kit is indigenous, so to speak, to the similarly evolved Cartesian X-Y-Z coordinate system. Nearly all our traditional tools, from the table saw, to the drafting machine, to the crosshairs of the cursor in your computer, are saturated with this self-same orthography.2 This is a powerfully coherent material culture indeed, and when reinforced concrete architecture made its appearance (let's say, from the late 19th century), it is little wonder that the shape of its moulds fell right in line. Although the potential for concrete to take other kinds of forms is latent, and many have dreamed of and sought such liberation, the cultural current of the right angle remains very strong indeed.

Today, concrete is an old material, and as such, habit has largely taken command of imagination. Conventional industrial methods of construction and design in concrete take place in a highly evolved traditional system where prismatic forms are a foregone conclusion. In this context, the making and detailing of concrete formworks is rarely the concern of designers. When construction takes concrete's plasticity into account at all, it is likely to be thought of as a merely utilitarian quality that allows for its transport and placement into its moulds.

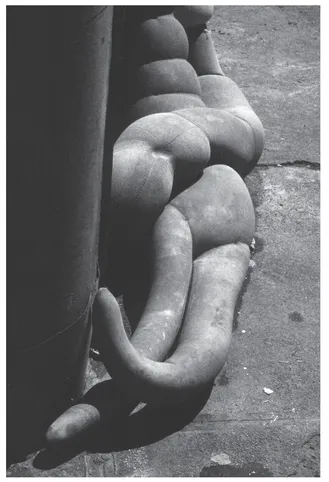

But the game is entirely changed when moulds are made flexible; the plasticity of concrete reappears to us as something extraordinary in a construction material (which it is). In a flexible mould, concrete is rediscovered as a wet, sensual, and responsive material. Its relationship to its mould is no longer passive, but an active one in which concrete's plasticity and weight play a particular and crucial role in determining its final shape. Concrete's activity in this new relationship constitutes an empowerment of plasticity itself in construction and design.

The arrival of flexibility and plasticity into construction alters form in a fundamental way. The biologist Steven Vogel observes that there are fundamental differences between natural and human-made forms: "Living structures are generally small, wet, and flexible, while human-made structures are generally large, dry and brittle" (Vogel 1981). Fabric-formed concrete, however,

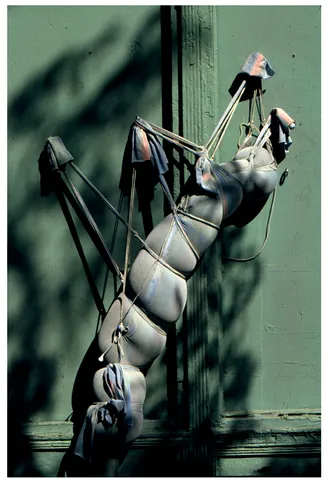

Figure 1.1 A permeable mould skin, under pressure, bleeding mix water (see pp. 56–9)

Figure 1.2 Storefront for Art and Architecture facade installation (New York, NY (1992)) (with Aryaya Asgadom)

presents a strange and temporary exception to this rule. When formed in a flexible mould, concrete begins life as a wet and flexible system, behaving precisely as a natural, biological structure might. As such, it assumes geometries that are often deeply reminiscent of those found in living things. Over a short period of time, however, this wet flexibility turns dry and brittle, making it as useful to us as any other human-made structure.

Before being filled with wet concrete, a slack fabric mould is largely indifferent to its shape – its form in space remains flaccid and variable. But when these two more or less amorphous materials are combined, they hold each other in a mutual embrace, producing an energized system of burden and restraint. A system of resistance is created where the materials themselves actively seek the shape of their own stability in the gravitational field. The bias towards the right angle and the necessity of a uniform-section disappear. The cast's final geometry is neither generic nor rigidly imposed. Instead, it is arrived at in a kinetic and highly particular way.

Figure 1.3 Storefront for Art and Architecture facade installation (New York, NY (1992) (with Aryaya Asgadom))

When form so clearly arises from an event, relations between designer, builder, and the material world are energized in a way that presents new prospects, both professional and intellectual. In such a flexible system, the materials in play can no longer be considered inert or passive. Instead they are alive to action as they engage in a kind of formal self-invention in real time. This aliveness is a direct result of the system's mechanical flexibility, which challenges the designer/builder to think of matter as a participant in determining form.3

Ursula Franklin, the Canadian scientist and observer of technology and culture, reminds us that technology is not a collection of gadgets or tools, but rather "a way of doing something". Franklin contrasts two different waysof-doing that she identifies as "prescriptive" or "holistic" technologies.

Prescriptive technologies seek to control the outcome of work by prescribing a step-by-step sequence of actions (think of tax forms, or military drills, or industrial "best practices"). Prescriptive production works hard to be independent of context, believing that all the essential parameters of production can be controlled (input and output) and that whatever is outside the production realm is external and irrelevant. Holistic technologies, on the other hand, require attention to, and reciprocal engagement with, a particular context. Engaged with a complex surrounding context, holistic production requires situational judgments and adjustments. Farming is a good example of this (Franklin 1990).

The act of construction, by its very nature, requires a combination of prescriptive and holistic methods. The contract documents produced by an architect, for example, are a form of prescriptive direction, but these are always an incomplete fiction of an ideal. The act of construction is, by its nature, filled with adjustments, change orders, and countless micro-improvisations. Everyone actually knows that, one way or another, the final construction will never exactly follow the original, prescribed design. In terms of prescriptive control, the result falls short of what was intended. From a "holistic" perspective, adjustments will be made, and solutions will be found as inevitable contingencies unfold.

As a noun, the word "mould" implies fixity; as a verb it implies action and change. Flexible moulds remain un-fixed until the very end of their action. That action is not one of strictly commandeering matter and events, but rather of finding an accommodation, within rigidly set limits. Boundaries are set and openings are sought, through which the material world is invited to offer solutions on its own terms.

Much is said these days about "working with nature", yet our industrialized methods tend towards increasing levels of control and efficiency. Our methods of prescriptive production seek to commandeer the material world in order to assure predictable or "optimal" results. Yet, attentive, responsive collaborations with the world-at-large would seem to be a prerequisite for anyone seeking to work "with nature". Holism and flexibility would be our allies, yet they are regarded with justifiable suspicion in an industrialized building culture and economy.

In this context, building with a flexible mould may be understood not merely as a technical enterprise, but also as a theater of freedom, restriction, control, and accommodation – i.e. a "little world" in which larger themes or actions are played out with some precision. As such, this practice is a precise functional analog for broader questions of "holism" in design and construction, and for how we engage with the physical world in general. The practitioner of such a flexible technology is called upon to be personally attentive and selectively yielding in ways that rigid materials and methods do not require. The designer/builder is brought face-to-face with this central and essential question: what actually needs to be controlled and what does not?

With a flexible mould, control is accomplished by choosing the specific materials in play, providing specific ...