![]()

Part 1

Individual art therapy with infants and toddlers

![]()

1

An odd mirror

Introduction

Simon, and his twin, Peter, were born at twenty-five weeks whilst their mother, Carla, was visiting relatives in her home country. Simon was the smaller and second-born twin. He was born blue and resuscitated at birth. An intensive-care infant unit separated Simon from his family. He was ‘stuck’ in hospital for the first five months of his life and Carla and the twins were ‘stuck’ overseas for eighteen months before returning home to the UK and to Steven, the twins’ father. Simon received repeated surgical interventions as a baby, including operations on his eyes, kidneys and stomach. He achieved oral feeding but after a stomach operation in his second year required a gastronomy button and tube. At the age of three and a half he had not returned to eating orally.

I use Simon’s own idea of being ‘stuck’ as a representation of his traumatic start to life, where ‘Trauma implies the baby has experienced a break in life’s continuity’ (Winnicott, 1971, p. 131), with subsequent defences against ‘unthinkable anxiety’ and the return to defensive confusional states (Winnicott, 1971, p. 131). I refer to Tustin’s idea of ‘psychogenic autism’ (Tustin, 1992), when ‘awareness of bodily separateness had been traumatic’ leading to ‘autistic reactions’ (Tustin, 1992, p. 11). I draw on Ogden’s concept of the ‘autistic contiguous position’, which is ‘a sensory-dominated, presymbolic area of experience in which the most primitive form of meaning is generated on the basis of the organization of sensory impressions at the skin surface’ (1992, p. 4). It is ‘a psychological organisation more primitive than either the paranoid-schizoid or depressive position’ (Ogden, 1992, p. 81).

In addition, Ogden’s notion of non-linear and interrelated developmental stages is a central theme. Ogden (1992) states that the different experience-generating modes (positions) (autistic contiguous, paranoid schizoid and depressive) ‘stand in a dialectical relationship with each other’ (Ogden, 1992, p. 10). Each mode has its own form of defence and symbolisation, and there is always a part of the patient functioning in the depressive mode. However, in psychopathology (e.g. that caused by trauma) there is a ‘collapse’ towards one of the modes. Furthermore there are areas of experience which are ‘defensively foreclosed from the realm of the psychological, for example … forms of “non experience”’ (Ogden, 1992, p. 39).

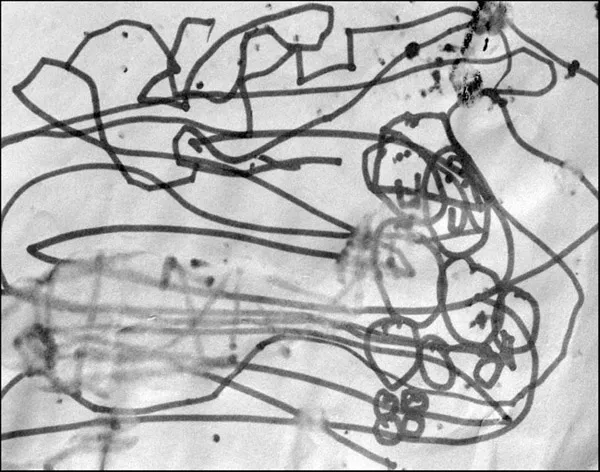

FIGURE 1.1 Drawing of twins by Simon, aged five.

The dynamic processes of twinning are explored; ‘twinship offers a narcissistic refuge’ (Lewin, 2009, p. 68), a refuge lacking containment (Bion, 1962, 1963) and which prevents development (Lewin, 2009) due to the absence of a generational gap between twins. ‘Twins are often premature and often surrounded by medical paraphernalia’ (Lewis and Bryan, 1988, p. 269). Children born prematurely can experience a range of medical and developmental issues, such as ‘post traumatic feeding disorders’ (Acquarone, 2003, p. 290). The developmental picture for a premature twin may be complicated and unequal with a ‘jumbling of developmental phases’ (Tustin, 1992, p. 97). The child’s experiences of invasive medical treatment is likened to abuse (Lillitos, 1990), and the hospitalised baby, with multiple caretakers, is at risk of emotional deprivation (Bowlby et al., 1956, Harris, 2005, Robertson and Robertson, 1989). Bonding with a premature baby is more difficult than with a full-term baby (Harris, 2005).

The nursery school and children’s centre

Simon was referred for art therapy by his nursery school when he was three years old. The school provides free nursery places for children from the age of two years in the local community and marketed places for babies and children from six months of age. The children’s centre provides universal services, such as group play sessions, and targeted services, such as family support to families with young children in the local area. Art therapy is well established in the setting. I offer supervision to the nursery team and individual, dyadic, family and group art therapy to children and their families. The art therapy initially took place in the nursery school and later in Simon’s primary school and is ongoing at the time of writing. Names and some details have been altered to protect confidentiality.

Referral and initial meeting with Simon and his parents

The referral noted Simon’s experiences of being separated from his family at birth and the many medical procedures that he had undergone. His intolerance of food and feeding with a gastronomy tube and his tendency to gag when touching viscous materials, such as sand or paint, were described. He experienced communication difficulties and had recently had grommets fitted. He was still wearing nappies.

In the initial meeting with Carla and Steven, I heard about how traumatic the first eighteen months of Simon’s life had been for all the family. The common complications of parenting twins (Lewin, 2009) were magnified by Simon’s prematurity, hospitalisation and the geographical separation between his parents. Carla movingly told me that Simon had been an unresponsive baby and she had to wait to fall in love with him (Harris, 2005). By the time I met the family there were strong, loving relationships between Simon and Peter and both parents.

I learned that Simon’s developmental situation was complex, and his social development was affected. He had little interest in his peers at an age when peer relationships are beginning to blossom for most children. The capacity to develop peer relationships is a developmental achievement linked to movement through the Oedipus complex and ‘the twin relationship may profoundly affect the resolution of … oedipal conflicts’ (Lewin, 2009, p. 68).

Simon had an almost permanent smile and a stiffness to his body movements. He would repeat his name as though it were a shield to manage contact with those around him (Sinason, 1992). Despite these difficulties he was a determined toddler. He had settled surprisingly well into nursery school given the intense separation issues that premature, incubated babies face (Acquarone, 2003, Baradon et al., 2005, Case, 2005, Harris, 2005, Lewis and Bryan, 1988, Mintzer et al., 1984).

Assessment period: the first four sessions

I met Simon in the nursery school garden. It took a few minutes for him to agree to come with me so we could ‘do art and think about his feelings’.

Simon explored the art room and took a pencil and paper. He made a small drawing, saying his name as he did so. He tried to pull the end off the pencil as though it were a lid. I wondered if this indicated some sort of confusion about how things came apart and fitted together and how we might fit together (Alvarez, 1992, Case, 2005, Tustin, 1992). He heard an adult voice outside and asked ‘Mummy?’ in a pensive voice that made me feel sad. I wondered aloud if he was missing his mummy.

In the following three sessions Simon communicated more detail about loss and absence. He told me his mummy and daddy were ‘gone’ and pointed to an empty chair. He frequently sighed, ‘Oh, no,’ but did not seem to expect me to respond. When I tried to capture the feelings behind these sighs Simon frowned at me as though my attempt to relate to his feelings was uncomfortable (Bion, 1959). In this way, he let me know that he could communicate but that thinking about feelings was problematic (Bion, 1959).

In the fourth session Simon drew ‘Mummy car stuck’ and made sounds which made me think about being constipated. Alongside being stuck there was a lot of messy water play where he repeatedly spilt water over himself and the room in a self-soothing activity which did not seem to need me to be present. This reminded me of the closed and sensory world of autism (Tustin, 1992) with its ‘machinelike predictability’ (Ogden, 1992, p. 59), omnipotence and lack of potential space (Winnicott, 1971).

In the assessment review meeting Simon’s parents told me he played with water when he felt anxious. We thought about him being ‘stuck’; both parents recognised this and told me how he could get stuck in oppositional or withdrawn moods for days. We thought about trauma related to Simon’s birth and medical interventions and about how he needed help to emerge from being stuck, withdrawn and hard to reach. His parents were keen for art therapy to proceed and we agreed for Simon to attend individual weekly sessions with regular reviews. We also communicated by email: Simon’s parents kept me up to date with any medical issues, absences and periods of ill health.

A dry and wet baby

The theme of water play continued into the fifth session. A daddy doll was placed in a pot of water and was ‘stuck’. Being ‘stuck’ reminded me of autism, characterised by a lack of change, the dominance of auto-sensory experience and truncated or underdeveloped symbolic capacities (Tustin, 1992). The experience of ‘stuck’ induced a sense of panic in me. Perhaps panicked parts of Simon were ‘stuck’ in the incubator and developmentally stuck in an omnipotent identification through twinning (Lewin, 2009) with an autistic, machinelike world of surfaces (Bick, 1968, Ogden, 1992).

Simon, born at just twenty-five weeks and incubated for five months, lost the deep connection with his mother’s body and with his twin, with whom he shared the womb (Piontelli, 1992). Tustin describes the baby’s traumatic loss of body connectedness with his mother as ‘a black hole catastrophe’ (Tustin, 1992, p. 18) which can lead to autistic defences as the infant desperately tries to fend off the horror of being disconnected (Dalley, 2008, Lewin, 2009, Ogden, 1992, Piontelli, 1992, Roberts, 2009, Tustin, 1992). This aspect of the water play could then be understood as an autistic behaviour, desperately creating sensation at the skin boundary (Bick, 1968) as a way of providing a fundamental experience of being a boundaried self. In this way the water play was life-sustaining but, paradoxically, it was simultaneously a turning away from relating and therefore in the realm of the death instinct, a return to the inanimate (Freud, 1920).

In contrast, Simon also used water in more relational play, as the following vignettes show.

Simon splashed water aggressively and tipped pots of water over the table. There seemed to be an aspect of the water play consistent with paranoid schizoid functioning – the quality of ‘attack’ in the deliberate spilling of the water and a subsequent countertransference wish in me to control this behaviour and to tidy up the mess (Aldridge, 1998, Case, 2003, Lillitos, 1990, Meyerowitz-Katz, 2003, Murphy, 1997, O’Brien, 2004, Reddick, 1999, Sagar, 1990).

In the following sessions I had an association that Simon’s water play represented something vital and alive. I was aware that he did not eat orally and his mouth and lips appeared dry. In my mind there was a link between the water and life-sustaining amniotic fluid. Previously, I had thought of him as a ‘dry baby’. This seemed to be a representation of his traumatic birth and of his premature emergence from an oceanic, womb-like feeling (Tustin, 1992, p. 98) into the dry incubator. But this new association with the water seemed to signal something different.

The mud game

Five months into the therapy Simon made his first clear representational drawing and said, ‘Baby Simon.’ I said, ‘Hello, baby Simon, how are you feeling?’ Baby Simon replied, ‘Sad.’ Simon stood in some spilt water and said it was mud. He cried out to me, ‘Help.’ He held his hands out to me, and I reached out and took his hands and played at pulling him out of the mud. He laughed hysterically at this activity but I felt a terrible sadness, echoes of which are still present as I write. Simon wanted help out of being stuck, but this help seemed to fill him with dreadful anxiety.

The following week more ‘mud’ appeared. I set a limit to the amount of water and paint allowed on the floor. Simon reacted angrily, shouting, ‘No!’ Perhaps the limits I set were an affront to his omnipotence. When Simon put his hands in the ‘mud’, he retched. We played the ‘pulling out of the mud game’ again, a game full of anxiety and panic, reminiscent of the terror associated with the catastrophe of the black hole and the ‘horror of bodily separateness’ (Tustin, 1992, p. 33). The mud game seemed to be a representation of Simon’s life-and-death struggle to manage feelings of emerging, of becoming a separate person and of his need for another person to connect with to pull him out of the cloying, sickening mud.

Following this game Simon stormed around the room, knocking over chairs and raging, shouting, ‘No!’ – a display of potency and aggression which left me shaken as though his ‘bottled up’ (Tustin, 1992, p. 30) feelings were exploding out of him. During these moments there was little sense of the safety of an autistic contiguous sensory floor holding him together (Ogden, 1992).

In the same session Simon found a lolly stick which he used as a tongue depressor. He told me to say, ‘Ahh’ and I opened my mouth; in went the stick so that I gagged. He gave me a stick and I pretended to put it in his mouth and look inside. This game went round several times and he seemed excited. I asked what the doctor saw. Simon said I needed medicine. I found a little pot but he took a pen and, syringe-like, tried to jab it into my mouth. He passed wind loudly and then retched, evidence of his confusion where oral experiences seem to be tangled up with feelings in his stomach and anus. He drew a car, shouting, ‘Help baby Simon, help baby Peter.’ I asked where the car was going. Simon shouted, ‘Help Doctor,’ communicating a strong sense of his terror and panic. I said, ‘The babies need a doctor, they need help.’ Simon rushed over to me and grabbed me in an aggressive hug as though gluing himself to me in order to fend off the terrible threat of separation. This was perhaps an enactment of adhesive identification with its lack of a phantasy of an internal space, a form of two-dimensional, autistic relating (Bick, 1968, Meltzer, 1975).

Tustin (1992) describes how the sensuous experience of the ‘nipple in the mouth’ provides the infant with a feeling of ‘rootedness’ which replaces the umbilical connection to the placenta of the mother. The life-giving nipple also ‘mediates sanity to the infant’ (Bion, 1962) without which the infant is ‘unrooted’ and at the mercy of primitive anxieties. Tustin describes how the ‘nipple in the mouth’ leads to other sensuous developmental progressions, such as ‘faecal stool in anus’ (Tustin, 1992). I think Simon had achieved a tentative sense of ‘rootedness’ after he left intensive care and the umbilical care of the incubator. His rootedness was then repeatedly disrupted by traumatic hospitalisations at developmentally sensitive moments, such as weaning.

After this session, and unusually for me, I cried as I wrote my notes. The ‘syringe’ penetrating my mouth, a representation of invasive, painful, phallic and mechanical care, replaced the nipple in the mouth experience and represented emergency medical help in lieu of a containing maternal object. It represented the treatment of the body as a thing and not as a person (Orbach, 2004). Simon’s desperate attempt to communicate his terror and urgency through projective identification (Bion, 1962) left me tearful and shaken; ...