1

Introduction

Robert E. Looney

Overview

With increased concern over global warming, countries are finding energy security at affordable supplies is no longer simply a matter of diversifying energy sources and expanding use of the cheapest type of energy. Energy security and affordable energy now come with a cost – greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change. With environmental sustainability as an additional energy goal, countries are often faced with the hard choice of improved energy security coming at the expense of either increased energy costs, or reduced climate security.

Focusing on these energy choices the theoretical underpinning of the volume is the idea of an energy trilemma,1 and the associated policy constraints facing countries as they attempt to achieve their main energy priorities. The trilemma implies that given a spectrum of different energy types, their associated costs, and their varying impact on climate security, countries will be forced to prioritize the goals of energy security, energy equity and climate security – high levels of all three will be very difficult to achieve at any one time. By opting for the top two, countries will likely find a deterioration in the third. For example, if clean, renewable energy costs more to generate than conventional power, improved energy security (more domestic sources of energy) and an improved environment (fewer greenhouse gas emissions) would result in higher energy costs

In terms of anticipating the likely success of global efforts at combatting global warming through voluntary cut-backs in greenhouse gasses, it’s useful to know if there is a predictable pattern of energy goal tradeoffs. Specifically, are countries in certain energy settings more likely to prioritize the same two energy goals at the expense of the third?

One can easily think of different national settings/environments where the trilemma tradeoffs may be fairly similar. For example, the major energy exporters automatically have less difficulty achieving high levels of energy security and energy equity. Other countries with limited domestic fossil fuel supplies can easily improve their environmental sustainability, and with it improved energy security due to a reduction in energy imports.

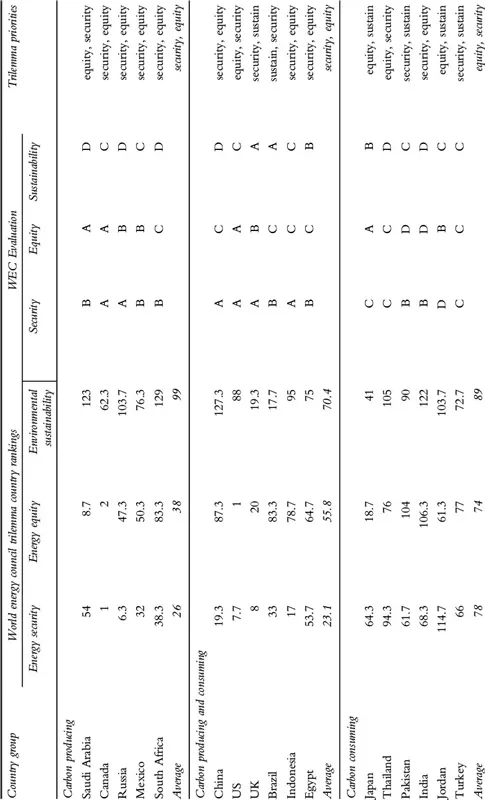

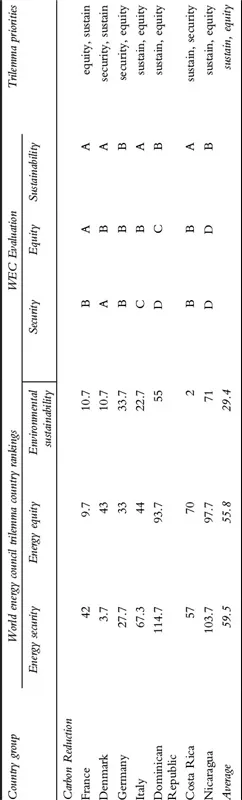

While a number of country groupings are conceptually possible, four provide logical starting points. On this basis, countries examined in this volume were placed in one of four groups: (1) carbon producing countries, (2) carbon producing and consuming countries, (3) carbon consuming countries. Several of the carbon consuming countries have shown a clear stated preference for the environment. Hence these were placed in a fourth group, the carbon reduction countries.

Energy priorities are also likely to be greatly affected by the global policy environment countries find themselves. The volume’s first section identifies many of these elements and discusses their relevance in affecting national energy choices.

Policy environment

A number of recent dramatic developments in energy markets and technologies are producing forces and consequences that are not yet completely understood. However, as Marcus King (Chapter 2) notes, some global trends are discernable and must be taken into account if countries are to design strategies to balance their preferred mix of energy security, climate security and economic competitiveness (energy availability). As he correctly points out, the development of clean energy technologies will be undertaken by many countries to maintain competitiveness while advancing the other primary goals of energy and climate security. Complicating the energy policy-making in most countries is the fact that rapid changes in clean energy technologies in such areas as nuclear energy, cleaner fuels and the possibility of geoengineering of climate will no doubt alter the impacts of trends currently underway. One thing is clear, however, countries successful in managing their energy trilemmas will be the ones able to rapidly adapt to this changing environment.

How well are most countries and international bodies prepared for the consequences of climate change? Francesco Femia and Caitlin Werrell see a large gap between the climate risks nations and peoples face, and the capacity and political will to respond to these risks. Given past failures they suggest the necessity of improving, augmenting, and possibly even creating new international, regional, national and sub-national structures for addressing climate change. But this is just a start. They feel serious responses will require that nations, and international institutions, place climate change at the top of the international security agenda, and find ways of collaborating on reducing those risks. This isn’t wishful thinking. Their well-researched essay shows why an international climate and security imperative is both necessary, and achievable.

The energy trilemma is not a universal constant that will be with us for the indefinite future. As Peter Hartley shows, the trilemma is purely a transition phenomenon since reducing fossil fuel combustion should increase energy security while also reducing potentially harmful climate change. Although we have two policy goals, they should be treated as one, since one policy instrument can simultaneously further both goals. The trilemma problem arises in the transition because the costs of reducing CO2 emissions are currently high, especially for developing countries. Eventually these costs, through research and development, will come down and at that time policies to force reduced fossil energy consumption would be unnecessary. He notes that in the transition policies aimed at encouraging basic research to lower the cost of new energy technologies, limiting the harmful consequences from climate change, or contending better with damaging weather events would yield far greater expected benefits for a comparable level of expected costs.

The costs of renewable energy will eventually come down, but not before a number of mistakes are made and money lost. While there are a number of good case studies to illustrate this point, one of the best involves a solar power project, the Desertec vision, in Northern Africa, Luigi Carafa and Gonzalo Escribano (Chapter 5) delve deeply into the factors that led to the failure of the project. They conclude that in the future the project’s troubles will require a rethinking of regional and industrial cooperation around a more inclusive narrative of sustainable energy development

Regional energy cooperation is increasingly seen as a means of achieving increased energy security, lower energy costs and a coordinated approach to achieving greater environmental sustainability. As one might imagine however, policy coordination across member countries with different energy needs, resource endowments, and priorities can be challenging. The two final essays in this section illustrate the difficulties and benefits of regional cooperative efforts.

In the first, focused on the EU, Benjamin Görlach, Matthias Duwe, and Nick Evans (Chapter 6) show there are a number of dynamics at work in EU climate and energy policy, which are not necessarily aligned. This has resulted in tension between unified EU targets on the one hand, and starkly different views of EU Member States about their future energy supply on the other hand.

In the second, Julia Nesheiwat (Chapter 7) ends the section on a more positive note. She sees regional coordination in energy systems not as a zero-sum game, but one that can benefit the national interest of all parties. Of course, there are always challenges and risks involved, but she shows that given the mutual problems of climate change and energy security, there is good reason for countries to cooperate. The integration of regional energy markets increases diversification of supply and delivery, cost-savings, and energy efficiency. Working together, countries can reduce climate change effects while promoting sustainable energy solutions and global energy security for the future.

With this background on energy trends, security concerns, climate developments, technological change and efforts at regional coordination the country case studies that follow show how many of these factors have played out in a broad spectrum of national settings. A number of interesting patterns emerge, leading to a set of predictions concerning where efforts at combatting climate change are likely to be the most concerted, and those where only limited progress can be expected.

Country studies

The first group of countries (Table 1.1) consists of carbon producing countries. In these countries energy production easily outstrips domestic energy usage enabling significant amounts of energy to be exported to international markets. Each country has consistently scored low in energy sustainability, in part because their abundant energy has simply enabled improved energy security and to a lesser extent, energy affordability to progress easily. However, just because a country has abundant fossil fuel supplies, energy security, as in the case of Saudi Arabia, is not automatically assured if the country becomes overly dependent on fuel exports. In addition to Saudi Arabia, the countries in this section include three other oil exporters, Canada, Russia, and Mexico. South Africa is the lone coal producer.

Table 1.1 Sample country characteristics

Notes: Trilemma data from World Energy Council Trilemma Data Base. Values are the average country ranking for 2013, 2014 and 2015

James Russell (Chapter 8) correctly assumes that it is unrealistic to assume a truly effective global accord to limit carbon emissions will be possible without the agreement of Saudi Arabia (and its Gulf State neighbours). Unfortunately, to date there has been little enthusiasm in that part of the world for a concerted effort to limit greenhouse gas emissions. The Kingdom’s energy priorities largely lie in providing the domestic population with low cost energy (energy equity in Table 1.1).

Professor Russell notes that while Saudi Arabia has done a good job in slowing down the world’s progress towards a climate accord, the Kingdom will face increasing international pressure to do its part in limiting carbon emissions. In this sense, the Kingdom is fighting a losing battle over climate change and its transition towards a more environmentally sustainable environment will be largely forced upon it, either indirectly through international condemnation, or directly through lower international oil prices as countries concerned over global warming transition to cleaner types of energy. Ultimately the shift away from oil internationally will force the Saudis to gradually diversify into more environmentally friendly forms of energy – solar and even nuclear. Professor Russell concludes that Saudi Arabia can survive for a time through oil revenues, but its days as a profligate welfare-spending state are slowly but surely coming to an end.

Canada and its oil stands are another country that has faced growing international pressure to cut back or even abandon production. Chris Bataille (Chapter 9) warns that, as in the case of Saudi Arabia, global climate security cannot be achieved solely by convincing fossil fuel exporting regions to stop producing. If pressure on one supplier is successful, as it seems to have been for the oil sands, there is a long list of potential suppliers waiting to take up the slack. Dr Bataille concludes that the best way to real climate security is to create real and perceived alternatives to fossil fuel consumption, and apply the necessary carrots (subsidies, development support) and sticks (technology performance regulations, carbon pricing) to encourage the great majority of firms and consumers to transition to low carbon options. As in the case of Saudi Arabia, this action will create a falling demand for oil, forcing Canada to limit oil sand development, and inducing the country to further develop green energies such as the country’s hydro energy potential.

Russia is another country where energy security and affordability take precedence over environmental sustainability (Table 1.1). As Jack Sharples (Chapter 10) shows, the result has been little in the way of reduced greenhouse gas emissio...