![]()

1

Introduction

The UK National Health Service design and procurement system now relies on a number of indicator tools built around a couple of key ideas. The first of these is learning from established practice and ongoing capital projects which feed knowledge back into new designs and the design process. The second is the notion of evidence-based architectural health care design, a process of basing design decisions regarding the built environment on credible and rigorous research to achieve the best possible outcomes.

The growing movement towards evidence-based health care design has largely emphasised a change of culture and attitudes and advocated for new ways of working. It has not focused on equipping health care clients and designers, and has resulted in a gap between aspirations for good and efficient design of health care buildings and the provision of the means to exploit the potential benefits of evidence-based architectural design. Design indicator tools not only aim to bridge this gap; they can also play a useful role in bringing together government clients, client bodies, contractors, design firms, local government and others to address issues of design and design quality, with improvements in quality a top priority of management today.

Concern with design quality increased in the 1990s following the UK government’s introduction of new policies on construction procurement and infrastructure delivery vehicles in the public sector. The result of these policies was Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs) followed by Public Private Partnerships (PPPs), and various types of construct/operate delivery vehicles such as Build Operate Transfer (BOT), Design Build Operate (DBO) and Design Build Operate Transfer (DBOT). However, these execution modes did not always produce high quality health care facilities. More specifically, studies pointed to poor performance, inefficient project management, poor building quality and, above all, low levels of client and user satisfaction. As a result, the UK government demanded that the construction industry implement better work practices, with the objective of achieving high levels of building quality while initiating and funding the development of design tools and guidance (NHS Estates 1994, NHS Estates Design Brief Working Group 2002).

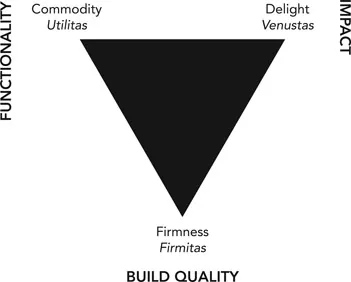

These measures by the UK government increased attention to the definition, measurement and monitoring of design quality in order to enhance the ability to create healing and therapeutic environments providing “function or commodity, firmness and delight”; in other words, “Well building hath three conditions, commoditie, firmness and delight”, as indicated in Principles of Architecture, Wotton’s translation of the ancient Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio’s three principles or essential qualities for architecture – in Latin, “utilitas, firmitas and venustas” (Wotton 1624/2011). In modern times these Vitruvian ideals have been translated into functionality (a good building should be useful and function well for the people using it), impact (a good building should delight people and raise their spirits) and build quality (a good building should stand up robustly and remain in good condition) (Figure 1.1). Monitoring and establishing accountability for the quality of the built health care environment is crucial for quality improvement, raising standards and achieving excellence in the design of new health care buildings.

1.1 Ancient Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio’s three principles or essential qualities for architecture in latin: “utilitas, firmitas and venustas”

Development of indicators and tools to aid designers and users of the built environments in thinking about design quality enhances the procurement and design process to deliver good environments that promote healing. Such tools can support health care managers and designers through both end-user involvement and an increased understanding of what patients and staff expect from the built health care environment. Design tools can facilitate the creation of patient-centred therapeutic environments which improve user satisfaction.

The context for these tools is indicated by the evidence-base underpinning them, and by the total life span of the project from inception through to the end of the building’s life cycle. The framework for the overall project process can be described by strategy, design, construction and operation; the key strategic and design issues relate to such things as improved health outcomes, impact on the community and so on, as well as the effectiveness of the roles and team expertise or skills to undertake the project work.

An evidence database essentially makes a link between structural and process measures of the estate and patient and staff outcomes. It is thus an essential tool in a system for measuring quality and safety in the health care estate. It indicates how the designed health care estate can impact on such things as length of stay, reduction of falls, rates of cross-infection, risks of clinical error and consumption of medication. It also shows very detailed results such as heart rates, sleep patterns, staff absenteeism and the like, and it can provide links to more qualitative measures such as patient satisfaction and staff recruitment and retention. The research in this field is international and extensive.

A database of such research for the Department of Health was started some years ago with funding from the old NHS Estates (Lawson & Phiri 2000). The database was updated annually until 2004 when NHS Estates was reorganised in the Department of Health (Lawson & Phiri 2003). We are now aware of around a thousand relevant items of research. The evidence suggests that factors that the architect/designer has control over can make significant differences to patient satisfaction, quality of life, treatment times, levels of medication, displayed aggression, sleep patterns and compliance with regimes, among many other similar factors. The database was cross-referenced to a similar literature search conducted in the USA by Professor Roger Ulrich’s team (Ulrich et al. 2004, 2008). Ulrich’s team looked for studies that were:

- rigorous, in that they used appropriate research methods that allowed reasonable comparisons and discarded alternative hypotheses. The research studies were assessed on their rigour, quality of research design, sample sizes and degree of control (e.g. Ulrich 1984).

- high impact, in that the outcomes they explored were of importance to health care decision-makers, patients, clinicians and society.

Previously, Rubin, Owens and Golden 1998 had identified 84 studies (out of 78,761 papers) since 1968 that met similar criteria and rigorous standards of hard science. Reviewing the research literature in 2004, they estimated that they would find around 125 rigorous studies. Ulrich’s team and Lawson’s team found more than 600 studies.

Since 1998, the increase in research related to the impact of the built environment on health care outcomes has increased at an exponential rate. There were 84 published studies at that time, and in 2004, the number grew to 600. Yet the debate continues about the reliability of this evidence to inform decisions about the design of health care environments. The interior designer can effectively use research as an iterative process throughout the design of a project, benefitting the decision making process. An exploration of the methods and tools that can be utilized have been described as well as some of the issues and pitfalls encountered as design professionals attempt to advance a research-based agenda.

(Jocelyn Stroupe, President, AAHID;

Health Care Interior Design Practice Leader,

Cannon Design, March 2011)

We therefore have good reason to place high confidence in the Lawson and Phiri (2000, 2003) Sheffield database and believe we identified the overwhelming majority of work in the field internationally. It was published annually on the Department of Health Knowledge Portal (KIP) until 2004. Users of KIP regularly consulted the database and there have been lots of requests to make the database widely available to NHS Trusts, their consultants and others such as researchers in health care facility design and operation. The database has also been summarised in a Department of Health publication (Phiri 2006). Studies range in size and scope. Some are small and little more than anecdotal, while others are major longitudinal controlled investigations. Some are multi-factorial and some much more parametric.

Overall, however, there is now little doubt that all this adds up to a significant body of knowledge that can no longer be ignored in the design of new health care facilities and the management and upgrading of existing ones (Lawson 2002). Studies suggest that in general, designs complying with this evidence may be capable of repaying any small additional capital costs on an annual basis (Berry, Parker et al. 2004). Other analysis suggests that the total operating costs of secondary care buildings may normally be expected to exceed the capital construction costs in less than two years (Lawson & Phiri 2003). It is entirely appropriate that summaries of all the original research, together with very basic analysis, should be made available to those people who wish to check or question its validity. This is in line with normal practice that allows others to judge the value of research for themselves and to go back to primary sources. However, it is recognised that such an approach is largely impractical in terms of design actions. Those involved in the briefing, specifying, commissioning and design of health care environments are unlikely to find the time or have the expertise to read a thousand items of original research. For this reason an overall picture is needed, not in terms of causal factors and theories but couched largely in terms of the design considerations and direction needed to achieve the results suggested by the research. In simple terms, clients and architects want to know roughly what sort of things they should do, what features of buildings they should control or elaborate, and what sorts of qualities of environment they need to produce (Lawson 2005).

Taken together, then, this new evidence-based approach has the potential to improve the quality of patient experience and, in many cases, health outcomes, while simultaneously saving time and costs. However, the generic evidence suggests that to achieve these benefits, designs will need to improve quality. So far most design guidance has tended to concentrate on compliance with minimum standards. This approach therefore suggests a new departure in focusing on ways to drive up quality in relation to the evidence specifically for health care environments.

Ongoing development and keeping up to date the evidence base that underpins the indicators and tools is essential to ensure that these respond to changes in clinical practice, new technologies and the frequent organisational re-structuring or new NHS landscape structures, health and social policies and supply chain that serve the NHS.

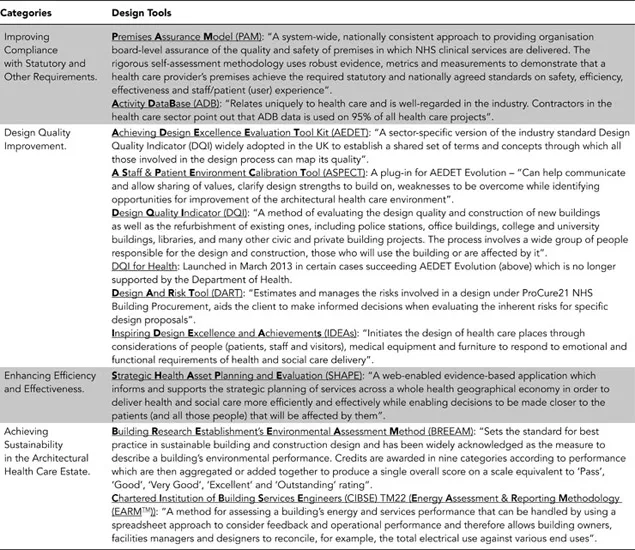

In this book the complementary design tools have been categorised into four main headings according to their aims and primary objectives (Table 1.1). These are: Improving Compliance with Statutory and Other Requirements, Design Quality Improvement, Enhancing Efficiency and Effectiveness, and Achieving Sustainability in the Architectural Health Care Estate. Each tool is described, reviewed and assessed in a typical case study application to show its important characteristics and the benefits of using the tool.

Table 1.1 Four categories of Evidence-Based Design Tools

-

Improving Compliance with Statutory and Other Requirements (PAM and ADB).

A growing challenge for all health care providers worldwide is the need to comply with statutory demands and legislation on the quality and safety of hospitals and other health care facilities. As for any major infrastructure project, the holistic process of health care facility design requires considerable multi-disciplinary input due to the many elements to be considered which must also comply with the regimes and protocols of the health care provider or operator. Tools which improve compliance with all these requirements, such as fire safety, are important in managing risk and in achieving the necessary approvals, licensing and certification while supporting the rapid diffusion of information and innovation.

Suitable tools are essential to facilitate the deployment of new health care service models and patient pathways, utilise the latest technologies where appropriate, and deliver excellent outcomes at lower cost.

-

Design Quality Improvement (ASPECT/AEDET Evolution, DQI, DART and IDEAs).

Concerns and raising expectations for improved design quality can be largely associated with various hospital building programmes dating back to the 1960s ‘Hospital Plan’ and up to the 1990s PFI Hospital Building Programme. In all these cases, a response has been the development of tools to help the design process and ensure the delivery of quality buildings and environments able to support a stepped increase in the adoption of world class scientific endeavour, which includes diagnostics, imaging, experimental medicines, assistive technology and telehealth.

Design quality matters and its continuous improvement is essential and crucial in enhancing health care services, delivering efficiency, flexibility of use and control of comfort levels to improve the patient and staff experience, including contributing to the positive effects of health and well-being. It is also now widely accepted that the physical environment impacts on our productivity levels, capacity to relax, ability to easily navigate where we are, and our ability to interact with each other. Design quality is therefore an important factor in determining the success of the places where we live, work and are cared for.

A study by the University of Sheffield’s School of Architecture Health Care Research Group into the NHS Estates Design Review System used 35 Design Review Panels and identified seven key design quality drivers: 1. Aspirations of the Trust; 2. Guidance and recommendations, 3. Championship (at board level), sponsorship and external reviewers (but not Design ...