1

Introduction

What social workers need to know

Marion Bower, Robin Solomon

This is a unique social work book. We are fortunate to have four chapters based on in-depth research, so we are able to talk about social work as it really is. Our other chapters describe new ways of thinking about key social work issues. Our authors demonstrate, using case material, how psychoanalytic theory can underpin effective interventions. Finally we suggest how some of these ideas can be integrated into social work training. A chapter by James Blewett describes the context of social work today.

We have not covered every aspect of social work. Our criteria for chapters are that they can increase the reader’s understanding of human nature. We have also added an afterword to the end of each chapter to contribute further ideas on the topic. Not all our authors are social workers, although they have all worked with social work problems. We feel it is an opportunity for social workers to hear from psychologists, psychiatrists and child psychotherapists. The book is the equivalent of a multi-disciplinary team. This is a companion volume to Psychoanalytic Theory for Social Work Practice. We cover some of the same issues but with different theories and case material. Reading the two books in conjunction will be a powerful learning experience.

On 14 February 2016 social work had the dubious distinction of coming top of The Observer’s list of stressful professions. The reasons for this must be complex, but we believe that what is missing in social work training is a theory of human nature which fits with the realities of practice. There have been various attempts to raise the status of social work, and attract students with high abilities. For example, there is now a fast-track route for students from Russell Group universities. In our view this misses the point. What social work students need is a theory of human nature which fits with the reality of what they will encounter in their practice. Able students will be the quickest to detect that they are being asked to do a job without the right tools (Anna Harvey’s chapter will take this issue further).

An example

A social worker has been asked to do a home visit to a young woman with small children. The health visitor suspected her of leaving them alone at night when she goes out to get drugs. The flat is filthy and chaotic, the client is tearful. Having arrived in a hopeful mood the social worker finds her head in a whirl and feels guilty and inadequate. Experiences like this are bread and butter social work. They are part of the reason the stress levels are so high. What could make it better? First the social worker needs to recognise that her feelings of confusion and guilt are her countertransference. The client is projecting into her feelings she cannot tolerate. Awareness of this can restore the social worker’s sense of professional competence. The social worker finds that when she talks to the mother, she cannot think about the children. This is probably because the mother cannot think about the children’s needs when she feels the need for drugs.

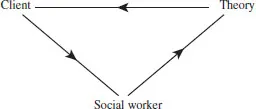

The role of theory can be represented in a simple diagram, shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The role of theory in aiding social work

The client projects difficult feelings into the social worker. The social worker turns to some useful theory which gives her space to think. She can then respond to the client in a different way. This process of using theory is not easy while you are in the middle of the hurly burly of a home visit. You can turn to the triangle when you are driving back to the office or doing the washing up at home.

The next section looks in more detail at how theory can inform practice. I will then give a brief account of some of Freud’s theories and some Kleinian and post-Kleinian theory. These ideas will reappear in all the other chapters of the book. There is also a list of useful texts at the end, for those who want to get to know the theory better.

Nothing so helpful as a good theory – Marion Bower

In 2015 the Conservative government pulled the financial plug on the College of Social Work. There was a great outcry from the College, but from the profession itself a resounding silence. The College had been intended to raise the status of social work. However it had half the planned membership, and I suspect many social workers felt it had no relevance for them. Social work cannot be turned into a high status profession without a body of knowledge which fits with the reality of their practice. Lawyers need a knowledge of law, doctors need a knowledge of the human body and its functions. Social workers need a knowledge of emotional development and human relationships.

I first became aware of the importance of a theoretical framework when I spent ten years organising infant/young child seminars for a post qualifying social work training. Students were expected to observe a baby or a young child once a week for ten weeks. They were asked to find a child about whom there were no concerns. In practice this meant observing babies with their mother or carer, and children in day nurseries. Students spent an hour each week observing, without making notes until afterwards. Each week the observers discussed their observations in small groups led by experienced social workers or child psychotherapists. The first thing that emerged was that most social workers were brilliant observers, and very aware of their emotional responses to the observations. The problem was that they did not have a well-developed model of human nature which would allow them to evaluate their findings. Some social workers knew about attachment theory. However in many of the nurseries children did not have an opportunity to form attachments. Their contacts with adults were fleeting even if they were ill or unhappy (obviously some nurseries were better than others). The social workers quietly sitting there ‘doing nothing’ were a magnet for children wanting to talk to them, show them a toy or just have a cuddle. Many of the students rated these observations and their seminars as the most helpful part of the course. Their value for many social work tasks was obvious. However when it came to writing an essay about their observations the students found it difficult. They had never been taught a theory of emotional development which fitted with their observational experience. They did not know how to interpret small children’s play or use their emotional responses as a tool to evaluate the observation.

Many child protection enquiries stress that the child concerned is not seen. In my experience children are often seen but the workers do not know how to evaluate what they see. As Janet Mattinson says, ‘there is nothing so helpful as a good theory’.

In one nursery, where staff were particularly unavailable, a little boy left on his own kept smiling and catching the eye of members of staff who usually smiled back. While he did this, he was building a house out of scraps of plasticine. I thought ‘He is making a meal out of scraps’. From a theoretical point of view, he is in a lonely situation, but he has the capacity to build up a ‘house’ of adult smiles. It is likely that a child like this has helpful people in his internal world and he re-created this externally.

My next example of the value of theory is an experience I had as a social work student. My placement was in a busy teaching hospital in the Child Development unit. It dealt chiefly with diagnoses of disability in children, but some adults with a disability were also seen. My first case was a man in his early forties who had multiple sclerosis. He was currently unable to walk, but had been refusing to have a wheelchair.

Mr A and his wife were Italian. Before the onset of Mr A’s disability he had been a head waiter in an Italian restaurant. Mr and Mrs A had a 16-year-old son, Giovanni. On my first visit I rang the door. Mrs A let me in. She called Mr A from the kitchen and I was appalled when he crawled in. Mrs A and Giovanni complained about his stubbornness. Over a number of visits the pattern repeated itself. I made futile attempts to persuade Mr A to accept the wheelchair. On one visit I arrived and found a nun (Mr and Mrs A were Catholic). I noticed that she had been offered tea and cake, I was only given tea. ‘She’s a good sort of nun,’ said Mrs A after she left. ‘She knows the price of cabbage.’ Although I was not familiar with transference I knew Mrs A felt that I did not know the price of cabbage.

My supervisor at the hospital was most amused by my lack of success. ‘When you leave they will think they’ve driven you away.’ ‘Oh no,’ I said, ‘I’ve told them I’m a student on a placement.’ After some thought I decided to raise this idea with Mr and Mrs A. To my surprise Mr and Mrs A beamed at me – ‘of course you’re leaving because we are too difficult for you. We hope you have better clients on your next job.’ I was amazed at the triumph of Mr and Mrs A’s feelings over the facts. Mr and Mrs A’s beliefs that they were driving me away was more ‘real’ to them than my announcement that I was a student on a short placement. This was my first encounter with the unconscious which, up until then, had just been a theory in a book. I was also surprised to see how it cheered up Mr and Mrs A when they felt I understood them.

My supervisor’s emphasis on the transference between me and my client is now a little old-fashioned. In fact it took place 35 years ago. Psychoanalytic theory and practice have developed since then. Now I would put more emphasis on the countertransference – how Mr and Mrs A made me feel. What I felt was helpless. I think Mr A, who had been a very active man, could not tolerate this feeling. He projected this feeling into his wife, and the two of them projected it into me. (I was a good target as I was so inexperienced.) I think if I could have reflected on this feeling I might have understood Mr A’s behaviour and perhaps been able to talk to him about what lay behind it.

I was lucky to be on a course which taught psychoanalytic theory. There was a period when this was replaced by a more sociological and political view. Of course these subjects are essential, but psychoanalysis reaches the important parts of clients’ minds that other theories do not reach. Psychoanalysis begins with Freud. Some of his ideas have been developed, others have been changed, but many of his concepts have had lasting value. One of these is the importance of listening very carefully to the patient/client. In social work we have learned to take what children say to us very seriously. Another of Freud’s discoveries was how much of our lives are dominated by emotions which may not be conscious (like Mr and Mrs A’s belief that I was leaving because they were too difficult for me). Finally Freud discovered that early experiences have a lasting impact on our personalities. This is an idea that is so widely accepted that we take it for granted.

In the next section I am going to describe the work of Freud and some of the psychoanalysts who came after him. Psychoanalysts refer to the people they treat as patients. Social workers used to refer to the people they worked with as ‘clients’. Now the term ‘service user’ is in fashion. I think this term is an evasion. It implies the interaction between worker and client is emotionally neutral. This is blatantly not the case. Some clients can stir up very unpleasant feelings in us, such as fear or hatred. This can feel ‘unprofessional’. It is not unprofessional to have these feelings – but they need to be used professionally. This theory will help you do this.

Freud

Freud spent all of his working life in Vienna. He started his professional life as a neurologist and made a number of interesting discoveries including the medical use of cocaine. As a Jew he found it hard to get advancement in the university so he turned to seeing patients in his private practice. Many of his early patients were Hysterics, patients who had a number of physical symptoms including paralysis which had no medical basis. The patients were often untroubled by the symptoms (‘belle indifference’), although their families were upset. Up until Freud the only effective treatment was hypnosis. Freud did not like using hypnosis so he and a colleague, Josef Breuer, simply encouraged the patients to say whatever they were thinking of – free associations. This has relevance for social work. Very often workers see a client or family with a fixed agenda. Sometimes we can learn a lot by letting people just talk. Freud and Breuer’s patients’ free associations often revealed that behind the symptoms were ‘forbidden’ thoughts or wishes, often of a sexual nature. Freud thought that one shortcut to these forbidden thoughts was by analysing the patient’s dreams. Once the patients had recounted their thoughts the symptoms usually improved. This treatment was more humane than other treatments available at the time. However it had one side effect. The patient developed an intense relationship to the doctor. One of Breuer’s patients claimed she was expecting Breuer’s baby (she was not, but Breuer took flight). Freud was not alarmed. He realised that the relationship with the patient could be a tool. The patient transferred on to the doctor significant figures from their childhood, for example a strict father or a depressed mother. You do not have to be a psychoanalyst to observe transference in action. The modern view is that transference permeates all relationships. Transference can colour a client’s perceptions of a worker. It is not unusual for a kind and helpful social worker to be perceived as cruel by a client.

As Freud saw more and more patients he was horrified when many of them described sexual seduction by a parent or other adults. At first he was alarmed that he had discovered sexual abuse on a massive scale. After a while he decided that patients were describing wish-fulfilling fantasies. This led him to suggest that young children were sexual creatures, but their sexuality is different to adults and located in different parts of their bodies. We now know that Freud had thrown the baby out with the bathwater. Young children are being sexually abused. However Freud’s concept of childhood sexuality has given us a better understanding of the impact of abuse on children’s minds. It is common when talking to abused children to feel confused whether or not it really happened. This reflects the child’s confusion, caused by fantasy becoming reality. Freud’s work also threw light on why many children and adults who have been abused put themselves in the way of being abused again.

Freud followed the events of the First World War anxiously. He had two sons in the army. In England there was a small but growing group of psychoanalysts, some of whom were army psychiatrists. Shell shock, accompanied by a host of physical symptoms, was extremely common. Psychoanalysis gained credibility because it was the only effective and humane method of treating it. Freud was puzzled that traumatised soldiers re-lived the horrific scenes in their dreams. He called the phenomenon of revisiting a trauma repetition compulsion. Sometimes this meant revisiting the trauma in waking life. This can take a number of forms. It is very common for patients who have been sexually abused to put their children at risk. A research project on sexually abused girls found that some seemed to invite further abuse by behaving in a seductive manner, for example sitting with their legs apart, exposing their knickers. It is not uncommon for children who are abused to be placed with foster families, only to be abused again. This is not to blame the children. Education of foster parents about this phenomenon may help protect abused children.

Sexually abused children often feel guilt. This is not rational and they are usually told they do not need to feel this. This is not enough. Abused children often feel guilty because their childhood sexual feelings are activated, making them feel responsible. When the abuse is incestuous and the parent is of the opposite sex the child can feel guilty because Oedipal wishes have been gratified, and there is a triumph over the parent of the same sex. Freud gave the name Oedipus complex to a phase of childhood sexuality when there is a wish to ‘marry’ the parent of the opposite sex. In the Greek myth an oracle tells Oedipus’ parents Jocasta and Laius that their son will kill his father and marry his mother. Horrified, they arrange for him to be taken away by a shepherd and left to die. The shepherd takes Oedipus away, but gives him to another king and queen. When Oedipus hears the myth as a young man he runs away from his foster parents. He meets his father at a crossroads. They have an argument and Oedipus kills him (not realising he is his father). He carries on to a city where the sphinx is holding the inhabitants in thrall. She promises to leave if someone can answer her riddle. Oedipus answers the riddle and as a reward he gets to marry the queen (not realising it is his mother). Many years go by and Jocasta and Oedipus have children. Oedipus discovers who he is. He is horrified and puts out his eyes in remorse. Jocasta hangs herself.

There is a lot of resistance to the idea of the Oedipus complex. But it is a story which has survived for 2000 years. Do people from other cultures experience Oedipal feelings?

The Ps were an Afghan family. Father had been imprisoned for his political beliefs. He escaped and fled with his wife and their daughter to Pakistan. In Pakistan they had a baby boy. After many difficulties they came to live in England, where they had a three-bedroom flat. School were concerned that the little boy constantly drew horrific scenes and people dripping with blood. It turned out they were things his father had seen in Afghanistan before he was born. When they came to a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) service it emerged that mother had banished father to a tiny cold bedroom and taken the boy into bed with her. Mother constantly complained about a madman in the next door flat who threw his furniture out. Unconsciously she felt she was mad to throw out her husband. The little boy in fantasy had entered his father’s traumatic experiences as well as taking his place in the parental bed.

Another way of thinking about family constellations has been described by Roger Money-Kyrle. He called it ‘The Facts of Life’. These facts have a biological underpinning. Where these facts are denied, consciously or unconsciously, something is going wrong. For example paedophiles deny the significance of generational differences. These facts are: 1) the infant is totally dependant on the mother or carer, 2) generational differences exist, 3) we are all going to die.

Melanie Klein

Klein was the most revolutionary psychoanalyst since Freud. Freud expanded our awareness of childhood and the influence of early experiences on development, but he never worked directly with children. Young children cannot lie on a couch and free associate. Klein was the mother of three children. Asked to see a young child she had the idea of giving the child some of her children’s toys. Klein saw play as the young child’s equivalent of free associations in the adult. Over time she standardised what she offered: little people, wild and tame animals, bricks, paper, pencils, plasticine, little cars, etc. These little toys can be put in a box or basket and carried with the social worker on a home visit. By giving a...