![]()

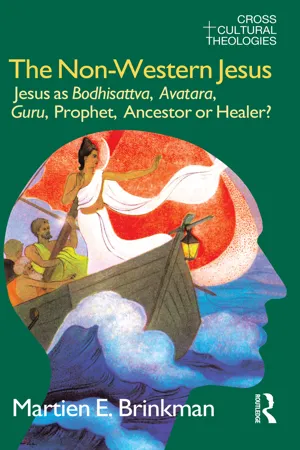

Part I: Where is Jesus “at Home”?

This book is about the meaning that is ascribed to Jesus in contemporary, non-Western contexts. Our guideline for assessing those strongly divergent meanings will be the term double transformation. This term entails that when a concept is transferred from one context to another, both the giver as well as the receiver are changed. In another context, the concept in question (the giver) receives a somewhat different meaning, whereas that concept also gives something new to, or changes, the new context (the receiver). In Jesus' case, this transference event (inculturation process) is more complicated, because the meaning attributed to him is always passed on in a community of transmission that wants to preserve unity with the past as well as with as many fellow believers as possible in the present. The methodological justification of an argument for a way of dealing with the many complications of this process that preserves this unity finally ends in the proposition that genuine transfer always presupposes solidarity with the new context. This solidarity will also include a critical element, however, because the Gospel-culture relationship is never a one-to-one relationship. There is always critical space between culture and the Gospel.

![]()

1 The Cultural Embedding of the Gospel

Must Jesus Always Remain Greek?

In what culture would Jesus best feel at home? That seems, at first glance, a strange question to ask — as if that were up to us or Jesus! Cultural influences are too complex to be simply shoved aside. We can define culture as a comprehensive system of meanings, norms and values by which people give form (meaning) to their material existence in a certain time and context. This concept of culture keeps the notions of "superstructure" and "substructure" together. The act of giving form and meaning always presupposes a certain, concrete, material existence. In using the word culture, we are not speaking exclusively of something lofty but of the broad complex process of giving meaning and form to all aspects of human existence. Both the way we think and the way we act are part of our "culture." Cultures are subject to change just as much as how we think and act is. It is people who make or break a culture, but a (collective) culture can also be a power factor over against the individual. That is why we can also state that culture stamps the individual.

As a rule, an individual is more of a bearer than a maker of the culture in which he or she lives. But one can, nevertheless, be critical of his or her own culture. Religion can play a role here, because religion is not only a final grounding and thus a confirmation of a culture but often a critical factor as well. Religion always wants to "exalt" the current pattern of norms and values or make them more profound. This can lead to a sharp critique of culture, which is why culture and religion seldom display a one-to-one relationship. Religion has often been used in the service of the reigning powers, but it has also often stood in the way of the powerful, whereby it has a cleansing, purifying role with respect to the existing culture.

To put this in terms of a model, it could be said that the relationship between culture and religion has never been simply that of a combination of the king who creates norms and the priest who sanctions them. There has also always been the prophet who criticizes any decline in norms. The role of religion can therefore change constantly, and the history of religion is full of changes with respect to its role. Because of those changing roles we are opting in this study for a rather broad threefold definition of religion. We understand religion as referring to the existentially experienced presence of a field of force (either personal or impersonal) that (1) transcends human existence, (2) influences thinking and acting, and (3) is expressed in shared symbols, rites and myths.

By appealing to that which transcends tangible human existence but influences thinking and acting, religion acquires the character of something intangible. Neither those in power nor its adherents can control it. Religion always represents something transcendent, something that hints at that which is "greater than." That explains why religion and culture are never completely identical, and it is for that reason that critical questions can always be asked about the nature of the relationship. Those questions do not concern the cultural embedding of religion as such — religion never arises in isolation and there is no single religion without any cultural attire. Rather, these questions explore the latitude between religion and culture. This also expresses the paradox that is always present in the culture-religion relationship: on the one hand, religion is part of an existing culture and more or less supports it, but, on the other, it also always claims to be in a position to criticize the existing culture. The relationship is therefore always characterized by both integration and segregation (separation).

This specific cultural attire does not constitute a straitjacket; religion and culture are not riveted to each other for good. Each religion — just like each culture, incidentally — has a certain dynamic (vitality) that allows change as a result of internal development or outside events. (Cultural) clothing can be changed. That is why the question arises: "Must God (or Jesus) remain Greek?" In 1990 the Afro-American Protestant theologian Robert Hood published a book by that title in which he asked if the Greco-Roman concepts in which the early church articulated the meaning of God and Jesus should also be normative for other cultures in other times. For believers in the non-Western world, he argues, those concepts hinder faith more than they help it. They make it harder rather than easier to pass on the faith.1 Thus, the intentional rooting of the faith in a non-Greco-Roman culture also always requires a certain uprooting from that Greco-Roman culture.

In contemporary non-Western theology, this point regarding the transmission of faith and thus also the relevance of faith is one of the most important arguments for a different conceptual apparatus for the proclamation of the Gospel. Non-Western theologians see a form of Western imperialism in the Western stress on the continuing validity of the terminology used by the early church. One specific inculturation —namely, that of the Greco-Roman culture that the West has appropriated — is absolutized. Other inculturations,: such as those in contemporary Africa and Asia, are considered second-class right from the start.

In fact, the criticism of Western theology often comes down to three things. At first glance, the first and second appear to be paradoxically related. But if we look at them more closely — taking the time factor into account — they are not necessarily mutually exclusive:

- Western theology is also contextual and therefore cannot simply be transmitted to other contexts.

- Western theology has lost touch with the concrete life situation of Western people and has become an abstract, academic activity.

- Western theology is modelled entirely on the requirements that obtain for Western science, which is still completely oriented to the demands of the Enlightenment.2

Hood's question has become even more urgent now that the heart of Christianity has shifted to the southern hemisphere. Usually based on the information contained in David Barrett's World Christian Encyclopedia,3 it is estimated that there are now about 2 billion Christians in the world, i.e. one-third of the world population. Of this number, 480 million live in Latin America, 360 million in Africa, 313 million in Asia, 480 million in Europe, and 260 million in North America. Given current demographic expectations, it is thought that in twenty years, of the total 2.6 billion Christians in the world, 633 million will live in Africa, 640 million in Latin America and 460 million in Asia. That is considerably more than half of all Christians. Europe is expected to have 555 million Christians and North America 312 million. This will make the latter the least Christian continent, as P. Jenkins indicates.4

Even if one holds that the estimations made by Jenkins and Barrett are somewhat high for Asia (they are very dependent on population growth figures and the growth — which is difficult to substantiate — of evangelical and Pentecostal churches), they are still probably indicative of a shift in global Christianity's centre of gravity. It would then mean a doubling of the percentage of Christians in Asia in the next twenty years from three Jo six per cent. This would be an increase of a few hundred million but, with a population of at least two and a half billion, it would still be a small minority.

Asian Christians often clearly constitute a minority over against Buddhist, Hindu or Muslim majorities. This is the case, for example, in countries like Japan, India and Indonesia. How can the dialogue on vital questions be maintained in the immediate environment under such conditions? What requirements should there be for an Asian theological language and Asian theological concepts? How much room is there for new concepts? What is the common reference point with Christians in other parts of the world? These questions can also be asked, of course, in relation to African Christianity. It is these questions with which this book is concerned.

The concept of inculturation is central. This concept and that of contextualization are sometimes used as synonyms, but we prefer the term inculturation. Contextualization often refers to the political, socioeconomic context and is viewed as a more critical concept than that of inculturation, which allegedly refers only to "cultural" phenomena such as language, symbols and rites. But such a concept of culture is too narrow, ignoring the influence of the "substructure," the conditions for material existence. At the start of this chapter we used a broader concept of culture, which included the so-called substructure. If it is clear that the conditions for material existence are also inalienably part of the concept of culture, then there is no objection to the concept of inculturation. To the contrary, it is even to be preferred, for this concept can express the normative element better, i.e. the point regarding the norms and values unique to each culture. The phrase religious process of inculturation refers to the transmission of a religious conceptual apparatus and pattern of values formed in a specific culture to another culture with its own religious conceptual apparatus and pattern of values. The appropriation of new concepts and values that is then necessary will always be accompanied by a process of change. In this study we will direct ourselves primarily to the nature of that process of change.

The most essential problem with respect to the inculturation of the meaning of Jesus in cultures other than the Greco-Roman one is the fact that decisive religious experiences are always bound to both time and place and also always transcend them in the ease of Jesus. In the Greco-Roman world, Jesus was never presented purely as a local hero (of faith) who was associated completely with his immediate environment. If that were so, one could never introduce him into other cultures. He made an impression on the people around him in a historical situation that can be described with reasonable accuracy. On the basis of that impression, a number of terms and titles have been ascribed to him that have certain meanings. These meanings, in turn, have to do with the role that people ascribe to others or things in their lives. In Jesus' case, it always concerns a role that transcends one's own specific experience. The particular is always connected with the universal.

For example, Jesus' disciples had the experience that he displayed the nearness of the divine in a unique way. On the basis of that experience, they subsequently ascribed to him a meaning that, in principle, he should have for everyone everywhere and at all times. Could that simply be done? Here we encounter the classic problem with which every religion with universal claims is confronted. At the foundation of such religions are very specific experiences, often more or less historically placeable, that also prove to be of great value for later generations in circumstances other than those of the specific original context of the experience. Later generations can realize that value only if they can make the experiences of the first witnesses their own; these experiences can apparently be broadened into universal experiences. True universality does not arise through abstraction but through the apparently unlimited possibility of connecting particular experiences with other more or less similar experiences and experiencing their authenticity in that way. Authentic universality always concerns a particularity — to cite the African Roman Catholic theologian Fabien Eboussi-Boulaga — that transcends its own limits.5

The well-known story of Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech at the end of the march on Washington in 1963 illustrates this nicely. At a specific place and at a specific time, King articulated his dream of the end of racial segregation between black and white. This particular, historically placeable experience by King has since then been recognized by millions of people all over the world because they have had similar experiences of racial segregation and longed passionately for the end of such. Thus, a bridge could be built between King's dream and the dreams of millions of others and could acquire universal significance.

When something is accorded universal significance, there are two specific experiences involved here: the original experience and the experience of recognition. Even though the latter can be experienced by millions of other people, it nevertheless remains very specific for the one involved and thus also unique. One could think here of the many millions who, down through the centuries and everywhere in the world, could identify with the original experience of the disciples concerning Jesus. Those (conversion) experiences are often unique markers in their lives.

The transmission of the meaning of Jesus concerns three such experiences. (1) First are the experiences of the disciples close to him: we find the expression of those experiences primarily in the four gospels in the New Testament. (2) Then there is the discovery of people in the Greco-Roman world around the Mediterranean Sea that they could recognize and articulate these experiences in their intellectual categories. (3) Next, there are the experiences of recognition by contemporary believers who can see the same divine nearness in Jesus through the Greco-Roman conceptual apparatus.

This process of recognition is anything but smooth, and sometimes it occurred only after a great deal of effort. One can think here of Paul's assertion that the Gospel was "a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles" (1 Cor. 1:23), The blood of the early martyrs of the church testifies to the tensions that this process of transmission evoked in the Mediterranean area. It is still an ongoing discussion today among New Testament scholars and experts in the history of the early church as to what was lost in this transformation process and what was added from the Greco-Roman world.

The threefold transmission or bridging process just mentioned is usually viewed in church history as a mediation process that was guided by the Holy Spirit, who is also called pontifex maximus, the bridge-builder par excellence, the mediator between past and present. This mediation process is faltering, however: the old mediation strategies, based primarily on historical exegesis, no longer appear to be adequate.

Thus, we are back at the problem with which we began: Must God Remain Greek? It seems more difficult to transmit the language in which the writers of the Bible and the theologians of the early church spoke about the meaning of Jesus to cultures that have been less formed by the Greeks and Romans than the West. The possibilities of identification sometimes fall short. Incidentally, that is also becoming increasingly true for the West. At first glance, the quickly growing Latin American and African Pentecostal ch...