What do language testers do?

Have you ever sat next to someone in a plane and been asked ‘What do you do?’. I usually try to avoid entering into the predictable discourse that inevitably follows. I do this by saying that I’m a teacher. Everyone has a schema for ‘teacher’. If I were to confess to being a ‘language tester’, the next question is most likely a request for an explanation, accompanied by a slightly baffled expression. Assuming I wish to embark upon this conversation, how would I explain in the simplest and quickest terms what a language tester does? Well, we give language learners tasks to do. The learners have to respond in some proscribed way to the tasks we set. We quantify their responses by assigning a number to summarise the performance. Then we use the numbers to decide whether or not they know the language well enough for communication in some real-world context.

This makes language testing and assessment a classic inferential activity. We collect a small amount of evidence in order to make a decision that leads to future consequences for the person who has taken the test. There are possible consequences for other people as well, such as employers, customers, patients and, indeed, passengers. From the rather simple explanation offered to my travelling companion, how many inferences am I making? It seems to me that there are quite a few, all of which deserve very close attention. Some of these are set out below. In a particular testing context these may be revised and expanded to make them more sensitive to the testing need being addressed.

- The tasks are relevant to the decision that is to be made:

- 1a.The content of the tasks is relevant.

- 1b.The range of tasks is representative.

- 1c.The processes required in responding to tasks are related.

- 1d.The tasks elicit pertinent (and relatively predictable) responses.

- The responses elicited by tasks are useful in decision making:

- 2a.Responses are elicited in suitable environments.

- 2b.Responses reveal target knowledge, skills or abilities of interest (constructs).

- 2c.Responses can be scored (assigned numerical value).

- The scores summarize the responses:

- 3a.Scoring criteria adequately describe the range of potential responses.

- 3b.Scores are indexical of changes in target constructs.

- 3c.Scores are consistent across the range of tasks that could appear on the test.

- 3d.Scores are independent of whoever allocates the score to the response.

- Scores can be used as necessary but are not sufficient evidence for decisions:

- 4a.Scores have clearly defined meanings.

- 4b.Decision makers understand the meanings of scores.

- 4c.Score meanings are relevant to the decision being made.

- 4d.Decisions are beneficial to score users.

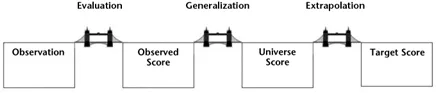

The notion that we are primarily concerned with making and justifying inferences is not uncommon. Kane et al. (1999) introduced the metaphor of the bridge to illustrate the inferences that he believes are involved in justifying the use of a performance test. Figure 1.1 below postulates the need for three bridges to explain the set of critical inferences in any testing context. Each of the pontoons between the bridges represents (from left to right): the observation that is made (O, or the response to the task), the observed score (OS) that is awarded to the response, the Universe Score (US), which is the hypothetical score a learner could be awarded on any combination of possible tasks on the test, and the target score (TS), which is the score someone would get if they could be observed performing over a very large range of tasks in real-world domains. Each bridge therefore represents an inference from initial observation through to a claim about what a learner can do in the real world.

The first bridge is from an observation to an observed score. That is, the translation of observed responses to numbers. Kane et al. (1999: 9) argues that this requires evidence for 2a and 3a above. It also clearly assumes 2c. The primary question that arises in this inference is whether or not we are capable of measuring language ability. We address this at length in Chapter 2.

The second bridge is from the observed score to the universe score. This is consistent with 3c above, and assumes 3d. However, in order to understand this particular inference we must very carefully define two terms. Ideas can become indistinct unless we are particular about how we use language to maintain clarity. In language testing and assessment, unless we make a clear distinction between the terms ‘test’, ‘form’ and ‘version’, errors can creep in.

Test: what we usually refer to as a ‘test’ is really the set of specifications from which any form of a test is generated. The test specifications are the design documents for the test and its constituent tasks (see Davidson and Lynch, 2002; Fulcher, 2010: 127–154 for a description of how to design specifications). They are also sometimes referred to as the ‘blueprints’ from which test forms are created (Alderson et al., 1995: 9). They tell the people who write the tasks and assemble the test forms what can occur on any individual form of the test. All the potential tasks should be similar to the extent that they elicit responses that are relevant to test purpose. The specifications therefore make explicit what features must not change because they are critical to the test construct and purpose, and what features are free to vary from form to form. In a sense, the term ‘test’ is an abstract term. We never see ‘the test’, only forms of a test.

Form: a test form is one realisation of the test specifications. It contains a unique set of tasks drawn from all the potential tasks that could be generated by the test specifications. Any single form is parallel to all other forms in terms of the critical elements that are not allowed to change. What makes a form unique is how the item writers have varied those features that are not fixed. These elements provide the freedom for variation in variable domain features that makes the creation of forms possible (Fulcher, 2003: 135–137). It is assumed that features that are subject to variation have little or no impact upon test scores.

Version: a version of a test is an evolution of the test specification. The specification may be changed to introduce a novel item type that better replicates the domain, or changes the nature of the scoring to improve the relationship between the score and the performance. Such an evolution changes all subsequent forms of the test. A version may therefore be seen as diachronic evolution, while forms are synchronic to each version. This is why it is important to have a numbering system for test specifications, with an audit trail that documents how the specifications have changed over time (Davidson, 2012: 204–205; Davidson and Lynch, 2002). Versions of the test specification constitute the history of test evolution, and act as a record of decisions taken over time to further define and improve the measurement of constructs.

We must be pedantic in insisting on these terms because all testing assumes that we can rely upon the principle of indifference (Keynes, 1921). This had previously also been known as the principle of insufficient reason, and applies to games of chance. In any particular game the use of different coins, dice or cards, should make no difference to the outcome of the game. That is, there is insufficient reason to suspect that a difference can be ascribed to the outcome because of the ‘tools’ being used. For the players, it is therefore a matter of indifference which coin, or which set of dice, is used. In gambling this is an essential part of the definition of ‘fairness’. In language testing the application of this principle means that the use of any possible form should be a matter of indifference to the test taker. The score obtained on any one form is supposed to be equiprobable with the score from any other form. We frequently refer to this as score generalisability (Schoonen, 2012). But this is not just a matter of fairness. It is also a central assumption for a critical concern in language testing: the unknown space of events. This is a topic we deal with a little later in this chapter.

For the moment, notice that I have compared test takers to players of a game of chance. The form that they encounter when they ‘take the test’ should contain a random sample drawn from all the possible tasks that can be generated by the test specifications. Yet, the problem is epistemological rather than aleatory, because we do not know that no outcome-changing difference exists in our forms in the same way that we can be sure about coins, dice or cards. Rather,we need evidence upon which to claim that, as far as we know, given existing research, there is no reason to suspect that there is such a difference.

Making these ideas clear and distinct is essential for us to realise the importance of the test specification. Without a ‘test’ as it is here defined, it is impossible to control forms. Without an understanding of control and variation in form, it is impractical to design research to test the principle of indifference.

The third bridge is the inference from the universe score to the target score. This is often referred to as the ‘extrapolation’ of the universe score to the target domain. It is the usefulness of the score for making a decision about how well a test taker is likely to be able to perform in a defined real-world context, and is typically said to comprise 1a, 1b and 4c above (Kane et al., 1999: 10–11).

FIGURE 1.1 The bridge analogy

Source: From Kane et al. (1999). Copyright 1999 by Wiley.Adapted with permission.

The fact that 4c depends upon 1a and 1b is an important observation. Test content must be relevant to the purpose of the test, which is specified in part by the description of the domain to which we wish to make a predictive inference. ‘Relevant’ is defined with Cureton (1951: 624) as ‘The relevance of a test to a job is entirely a matter of the closeness of agreement between the “true” test scores and the “true” criterion scores’. (We extend the term ‘job’ to refer to any target domain that is defined in the statement of test purpose.) This is rather broader than simply content, and to explore this we step into the world of science fiction. In the best tradition of philosophy, let us do a thought experiment. According to Wikipedia, a parallel universe is ‘a hypothetical self-contained separate reality coexisting with one’s own’. This is like Putnam’s (1973) notion of ‘twin earth’,but in this example there are many hundreds of earths. Each universe is completely identical in every respect but one. Most importantly,tests exist in every universe,and are used to make judgements about employment and education.On one particular day,you are required to take a language test upon which your future depends. You take the test in each parallel universe that you inhabit. So you take the test hundreds of times. The one difference in each universe is that you take a different form of the test. As each form is generated from its specification, they should be just as parallel as the rest of the universe, even though the content is different to the extent that the forms are allowed to vary. As you take the test at the same time in each universe, there is no learning effect from one administration of the test to another,and you know nothing about the performance of your alternate self. Unbeknown to you, there is an omnipotent and omniscient being who can move freely between universes. The Universal Test Designer is the one person who is able to exist in each universe simultaneously, and collect the scores from each test you have taken. In this thought experiment your score will not be identical in each universe. You will get a spread of scores because of random variation or error. Very occasionally you will get a very low score,and equally rarely you may get a much higher score than you would normally get.But in most of the tests you will get a score that clusters closely around the mean, or average score. This average score from the potentially infinite number of test forms is your ‘true score’.

We will uncover the rationale for this in Chapter 2. However, you will observe that in our own limited universe we are making a huge leap of faith. We only have access to one score derived from a single administration of one form of the test. Yet, we infer that it is representative of the ‘true score’. Next, we infer that this true score is comparable with the target score. This is done primarily by a logical and content argument that links test content and response processes to the content and processes of real-world communication. That is, we need a robust comparison between the test and the target domain, which is specified in the purpose of the test. Thus, Messick (1989: 41) has argued that:

it would be more apropos to conceptualize content validity as residing not in the test, but in the judgment of experts about domain relevance and representativeness. The focus should not be on the test, but on the relationship between the test and the domain of reference. This is especially clear if a test developed for one domain is applied to other similar domains.

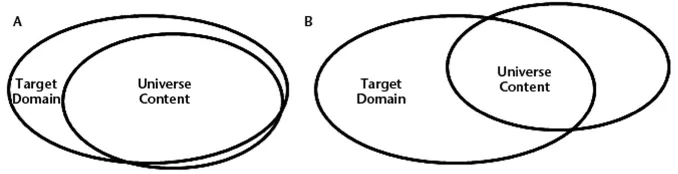

Messick argues here that the degree of relevance and representativeness is likely to be higher for the primary purpose for which a test is developed. We may represent this as a Venn diagram in Figure 1.2, where A represents the primary and B a secondary test purpose. In illustration A we can see that the space of the target domain not covered by the universe content is smaller than in illustration B, thus indicating it is more representative. In illustration B we see that the space in the universe content that is beyond the target domain is larger, thus indicating a significant lack of domain relevance.

FIGURE 1.2 Potential relationship between universe and domain content

Fulcher and Davidson (2009) employ the metaphor of architecture to further understand the relationship between the universe and the target domain. The test specifications are the architectural designs, and the resulting forms are like buildings. Tests, like buildings, have a purpose, which is based upon the specific target domain language uses. Just like buildings, if the purpose is changed, they are no longer entirely relevant to the new users. One example that is becoming very familiar in Western Europe is the conversion of churches to flats, restaurants or retail outlets. Architects are required to alter the design to accommodate the new use, to meet health and safety requirements, and comply with building regulations. In language testing repurposing must trigger a review of the specifications and any necessary retrofits that are required to make the test relevant and representative to the new purpose. This is a matter of realigning the universe content and target domain.

The quotation from Messick above indicates that the primary source of evidence to justify the inferences made in the third bridge is expert judgement. This may be from applied linguists or content specialists. They are asked to look at test tasks and decide to what extent they are ‘typical’ of the kinds of tasks in the target domain, and whether the range of tasks is representative. However, it is increasingly the case that direct study of the target domain takes place, and can be aided by the development of domain specific language corpora. This is not in fact new. Discourse analysts have long been concerned with domain description that could be put to use in comparing universe content and target domains (e.g. Bhatia, 1993). But it is only recently that this approach has been applied in a language-testing context. Such research has taken place to support the selection of tasks to represent communication in academic domains (Biber et al., 2004; Biber, 2006; Rosenfeld et al., 2001), and in service encounters (Fulcher et al., 2011). This, in turn, draws on a much older tradition of job descriptions as a basis for assessment design (Fulcher a...