What do the above scenarios have in common? Have you observed interactions similar to the first two between parents and children? Was it at the supermarket or library or walking down the street? Have either you or any of your colleagues held this type of workshop?

What Is Parent Involvement?

Definitions of Parent Involvement

Parent involvement in children’s education includes actions taken by parents that promote learning for their children. The definition of parent involvement has evolved over time from a narrower concept of parent involvement, focused on parents’ participation in school activities, to a more inclusive definition that underscores the importance of parental activities in the home, school, and community (Vukovic, Roberts, & Green Wright, 2013). Although there are variations in current definitions of parent involvement, we find that the following definition stands out as broad enough to encompass all forms of parent involvement: “Parent involvement is the participation of parents in every facet of children’s education and development from birth to adulthood, accompanied by the recognition that parents are the primary influence in children’s lives” (Edwards, 2009, p. 8). Other definitions of parent involvement delineate the forms of involvement. For example, Ma (1999) breaks parent involvement into three categories: behavioral (participation in school events), personal (cares about student’s life out of school), and intellectual (exposes their child to intellectual concepts).

A commonly utilized definition of parent involvement was developed by Epstein (1994), who described the following: 1) basic obligations of families; 2) basic obligations of schools to effectively communicate with families; 3) involvement at the school building; 4) family involvement for learning activities at home; 5) decision making, participation, leadership, and school advocacy; and 6) collaborations and exchanges with the community. Some researchers extend the definition of parent involvement to include not just actions parents take but also their motivation and attitudes (Vukovic et al., 2013). Often what parents do to promote learning is not conscious/formal learning sessions, yet the ways they talk and play with children and their attitudes about learning are all part of parent involvement.

Take a moment to think about your definition of parent involvement. What types of activities do you think are critical for parents to engage in with their children? What has shaped your view of parent involvement? Your definition of parent involvement will likely vary from the definition of other teachers you encounter. There are many factors that might influence how you think about parent involvement, including your past experiences with parents of the children you have taught and the ways your parents were involved in your own schooling. Your views may also have been shaped by your cultural background, your teacher preparation program, and by other teachers with whom you interact. For example, one teacher might describe parent involvement in terms of parents’ participation in events such as back-to-school night or parent–teacher conferences. Another teacher might define parent involvement in relation to how much homework support parents provide for their children. A third might think of parent involvement as whether or not parents volunteer to come to the classroom and share an expertise.

Moreover, if you ask parents how they would define parent involvement, you will hear different answers depending on parents’ own school experiences as well as their linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Some parents might define parent involvement as preparing their children to respect their teacher and to behave well in class (Delgado-Gaitan, 1991; Parra & Henderson, 1982; Valdés, 1996). Other parents might view parent involvement as helping with and monitoring homework. Some parents are less clear about the specific role they should take but are certain they want their children to succeed. In talking to one parent from Guatemala who had lived in the United States for seven years, she explained, “I want them to be something more than I am.”

Framework of Parent Involvement

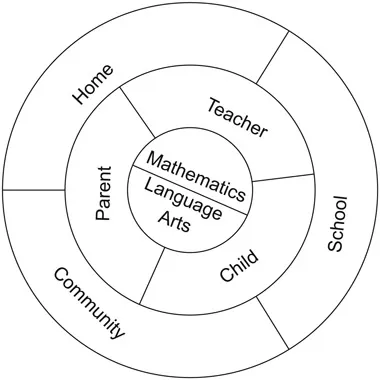

Figure 1.1 Framework of Parent Involvement

When we think of parent involvement we consider three interrelated factors, as depicted in Figure 1.1. First, we think about where the involvement is taking place. The context for the learning could include the school, the home, or the greater community. Second, we consider who initiated the learning opportunity. We recognize that parent involvement may include a series of interactions between parent, teachers, and children and other school personnel, but we also believe that parent involvement is primarily initiated by the teacher, the parent, or the child. Last, we consider the type of learning that is taking place. We think of this broadly to include skills and content being learned in mathematics and language arts as well as attitudes and expectations in these content areas.

As you look at Figure 1.1, try to imagine each of the three parts as separate rotating layers. With this in mind, you could line up home, parent, and mathematics indicating the learning taking place in the home, initiated by the parent, with a focus on mathematics. For example, the parent could invite the child to play a game such as Yahtzee that strengthens multiplication and division skills. Alternatively, rotate the layers to line up teacher, school, and language arts indicating the learning taking place in the school, initiated by the teacher, focusing on language arts. For example, in this case the teacher might have invited the parent to come into school and do a read-aloud about Thanksgiving.

Think about the opening scenario where the father and daughter are in the supermarket talking about the words listed on the deli board. In this case, the parent involvement activity is taking place in the greater community. The initiator of learning is the child who begins by attempting to sound out words and the father builds on this experience by adding in new information that his daughter does not know. In this case, the content of the learning is early literacy because the father is providing foundational knowledge about letter names and sounds.

Now, return to the supermarket scenario and imagine an older child with her mother. As they are waiting, the mother asks the child to figure out how many different sandwiches could be made if the deli sold three types of meat and two types of cheese. In this case, the parent is the initiator of the learning and the content of the learning is multiplication because the mother is asking the child to reason about the different combinations of sandwiches.

Examples of Parent Involvement at Home

Much of parental support takes place outside of the school environment. Some of the ways in which parents support children at home include:

- Helping with homework

- Monitoring homework

- Extending the school-based learning

- Teaching children foundational knowledge

- Helping children when they are having difficulty

- Expressing interest in children’s schoolwork

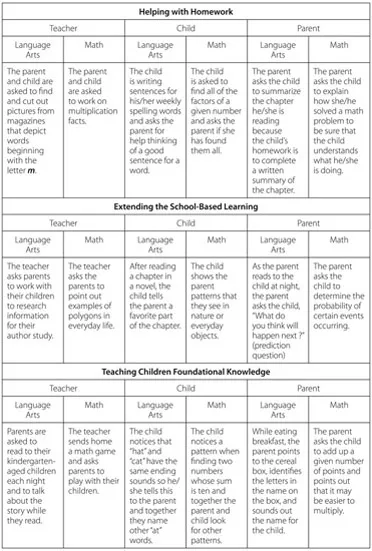

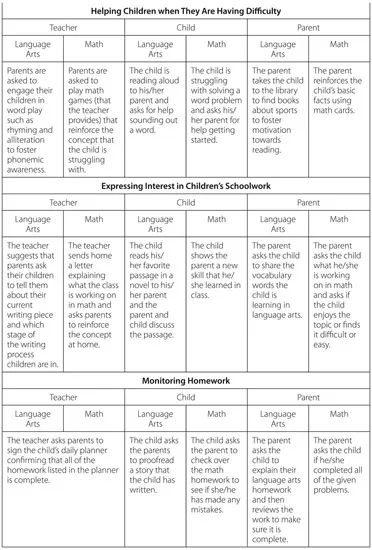

In Table 1.1 we describe several examples of parent involvement in language arts and mathematics that can take place in the home and be initiated

Table 1.1 Examples of Parent Involvement in the Home

by the teacher, parent, and child. The examples will help you to become familiar with our framework for parent involvement and appreciate the ways in which you as teachers can initiate home-based parental involvement in math and language arts. For each of the types of support, we show how the activity could be initiated by the parent, teacher, and child.

Examples of Parent Involvement at School

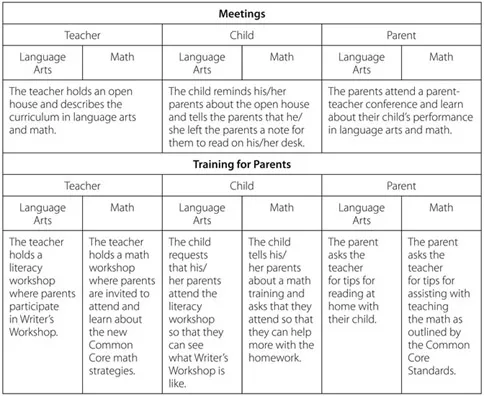

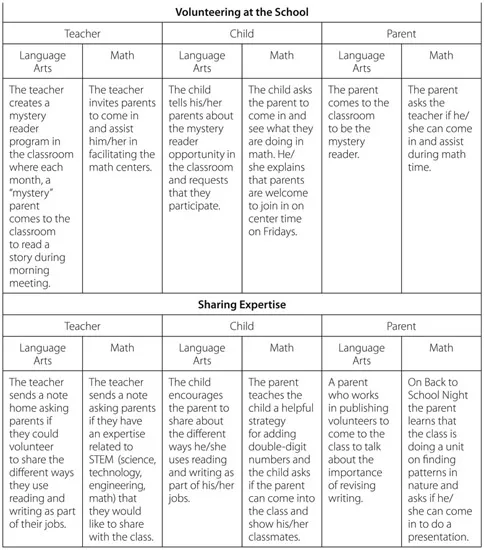

Parent involvement has traditionally been thought of as the time that parents spend volunteering in the school and/or classroom and attending school functions. In our framework, we extend parent involvement at school to include other school-based activities that focus on math and literacy. These activities include attending meetings with teachers, attending parent training, volunteering in the classroom, and sharing an expertise. In Table 1.2, we present examples of parent involvement activities at school and delineate them according to the initiator (parent, teacher, and/or child) and the specific focus of the involvement.

Table 1.2 Examples of Parent Involvement at School

In the context of the school, the initiator of the parent involvement activity is often shared between the teacher, parent, and child. For example, the teacher may initiate by holding family literacy night. A child can also be seen as an initiator in this example when she reminds the parent of the event and asks her to go to see her latest writing piece. Parents could also be seen as initiators if they choose to participate in the event and follow through with suggestions at home.

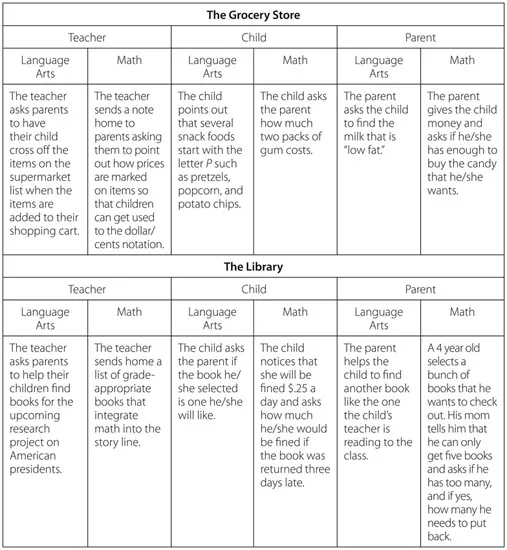

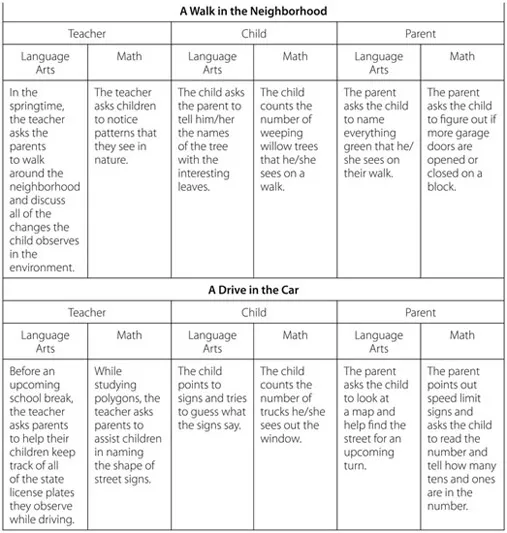

Examples of Parent Involvement in the Community

Parents can be involved outside of the school and the home by bringing math and language arts into other contexts. We recognize that learning opportunities occur outside of school and home, so parents can capitalize on children’s natural curiosity. Learning opportunities can take place in the grocery store, the library, a walk through the neighborhood, or a drive in the car. Table 1.3 offers examples of learning that can take place in the community in math and language arts initiated by parents, children, and teachers.

Table 1.3 Examples of Parent Involvement in the Community

The Importance of Parent Involvement for Children’s Learning

Impact of Parent Involvement on Literacy Development

For those of you who have been teaching for a while, you already know that when parents are more involved in their children’s learning, the children are more successful. Researchers in the areas of literacy development have proven the connections between parent involvement and academic learning with numerous studies. One easy way to see the connection between home reading experiences and children’s emergent literacy skills is to observe kindergarten children at the beginning of the school year as they sit in the library corner and “read” books to themselves and their friends. You might notice that some of the children will be holding the books upside down or turning the pages from right to left instead of left to right. Other children will be using their fingers to track the print even if the words they are saying are not the words on the page. If children are reading to each other, you might observe them pointing to a picture and saying to a friend, “What’s that?” These reading behaviors demonstrate children’s concepts about print that are often a reflection of the reading experiences children bring with them to school.

Early home language and literacy experiences like the story book reading that prepared the children described above are linked to a number of language arts areas including vocabulary development, phonological sensitivity, understanding of books and story structure, and knowing letter names and sounds (Burgess, Hecht, & Lonigan, 2002; National Early Literacy Panel, 2008; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2002). Reading to and with children, in particular, has been linked to literacy performance in large-scale international studies of student reading performance. In one such study, higher frequency of parents and children reading together was linked to better performance in language arts:

For example, students whose parents reported that they had read a book with their child “every day or almost every day” or “once or twice a week” during the first year of primary school performed higher in PISA 2009 than students whose parents reported that they had done this “never or almost never” or “once or twice a month.” (OECD, 2010, p. 95)

In addition to story book reading, there is also evidence that when parents supported early reading development with such tasks as alphabet recognition and word reading strategies, children had better literacy performance (Sénéchal & Young, 2008). Children’s early language experiences also influence their literacy development, including vocabulary and language based play (Dickinson, Griffith, Golinkoff, & Hirsh-Pasek, 2012; Fernandez-Fein & Baker, 1997).

Impact of Parent Involvement on Math Development

Although we know that parent involvement in learning is important for children’s mathematical development, there is much less research in this area as compared to literacy. The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM, 2000) stresses the importance of working with parents as partners in the efforts to bring change to the mathematics education of all students. However, family involvement is less common in math than in literacy. Factors that contribute to this inconsistency include a disconnect between real-world and “school math,” parents’ negative experiences with math, parents’ lack of confidence in math, the difference in how mathematics is taught now versus when parents were students, and the fact that teachers are less sure of how to involve parents in math.

Early Interventions

The ways parents support their children’s early math development can be broken down into two categories: direct skill based activities such as counting and recognizing shapes, and indirect learning activities such as games that don’t directly teach numeracy (LeFevre et al., 2009). It is important to note that indirect activities are just as powerful as direct activities in supporting children’s developing fluency with numeracy skills. If you are a kindergarten teacher, during math instruction you might notice that some children are fluent in counting up to 100 while others have difficulty counting more than five objects. This discrepancy may be caused by the type of play that young children participate in at home. While playing games or with certain toys, such as Legos and building blocks, children are engaged in much critical thinking an...