eBook - ePub

Local Economic Development in the 21st Centur

Quality of Life and Sustainability

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Local Economic Development in the 21st Centur

Quality of Life and Sustainability

About this book

Provides a comprehensive look at local economic development and public policy, placing special emphasis on quality of life and sustainability. It draws extensively on case studies, and includes both mainstream and alternative perspectives in dealing with economic growth and development issues. The contributions of economic theories and empirical research to the policy debates, and the relationship of both to quality of life and sustainability are explored and clarified.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Local Economic Development in the 21st Centur by Daphne T Greenwood,Richard P F Holt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Defining Economic Development, Quality of Life, and Sustainability

1

Economic Growth vs. Economic Development

We wrote this book to answer rising concerns about the relationships among economic growth, quality of life and sustainability in state and local economic development.1 One of our underlying themes is that these issues must be tackled jointly. Too often, they are addressed one at a time in community planning, state and local budgeting, and tax policies. If local governments do focus on sustainable development or quality of life, it is usually through separate policies and initiatives. Taking a more comprehensive approach will make clear the linkages among economic growth, quality of life, and sustainability.2 Differentiating economic growth from economic development is a good place to start. Economists and policymakers often speak of growth and economic development as if they are the same. We make a very clear distinction between them.3

Economic Growth vs. Economic Development

Economic growth is traditionally defined as increased total output or income. People also refer to growth when there is an increase in population or in land area as a city “grows” beyond its traditional boundaries.4 Economic development, on the other hand, is much more. We define it as a broadly based and sustainable increase in the overall standard of living for individuals within a community. Conventional economics has equated economic growth with economic development, implicitly assuming that growth will bring improvement in quality of life and the standard of living. However, many now question this assumption. This shows up in the questions asked by community quality-of-life and sustainability groups and the indicators they choose (Chapter 8). Some scholarly work in economics (Daly 1996, Holt 2010a; Greenwood and Norgaard 1994) also raises these questions. Standard of living refers to overall well-being that goes beyond income. For example, if per capita income (income adjusted for population) increases but there is more crime and congestion, then the standard of living may have fallen.

This does not mean we are “antigrowth” or that economic growth is unimportant for well-being. People are generally better off with higher incomes than lower, because they can more easily afford higher quality goods and services. Higher pay can also allow more leisure or earlier retirement. Economic growth often brings a vitality that accommodates change and innovation. More income and consumer spending create local retail opportunities and can bring higher tax revenues to support schools, parks, and roads. However, growth can also subtract from quality of life and lead to unsustainable development. Growth can lead to urban sprawl and increase the cost of public utilities such as water or power. It can affect the social life of communities if neighborliness or civic engagement is harder to maintain. It can mean changes in the pace and lifestyle that people experience at home and at work that are not always positive. Growth can produce higher levels of carbon in the air and pollute water with agricultural pesticides. As we explore later in this book, rapidly rising incomes can also create a “negative trickle-down” effect through a competitive race to consume that leads to less leisure and satisfaction rather than more.

The net result is that growth can either contribute to or subtract from economic development, depending on the way it occurs. Just as important is that economic growth may not always be the most important factor in improving perceptions of well-being. Surveys indicate that while average income has risen over the past forty years in the United States and the countries of Western Europe, measures of happiness are about the same as they were at lower levels of income.5 Studies from an even broader group of countries confirm this weak relationship between growth in income and improvement in other measures of the standard of living (Slottje 1991). After basic levels of needs are met, nonmarket elements of quality of life become more important than additional income.

Understanding the fundamental difference between growth and development is the first step in looking at the future of economic development in a new way. Economic development is multidimensional, while economic growth is one-dimensional.6 Defining economic development more broadly than economic growth should encourage community leaders and elected officials to consider both the positive and negative impacts of all types of growth and to look beyond the immediate economic effects of their decision or policy.

The Importance of State and Local Actions to Sustainable Development

Another feature of this book is its focus on local development.7 We believe that thinking and acting locally, as well as globally, are necessary when addressing quality of life and sustainability. Much of the public discussion of environmental and sustainability issues has focused on national or global issues, but sustainable practices may gain wider acceptance when tied to local (rather than global or national) outcomes. Moreover, while many economic and environmental forces transcend local boundaries to affect the globe, the source is often found in local actions. This means that some very important aspects of dealing with national and global issues must start at the local and state levels. This is where people have direct experience and can have a direct impact.

Beyond environmental and quality of life issues, there are other reasons to focus on state or local economic development. Although the role of the federal government is important for national economic growth and stability, its influence and impact on local areas can be quite limited. Just as a rising tide does not always lift all individual boats equally, growth rates in the macro economy do not have the same effect everywhere. Economic, geographic, and historical realities cause substantial regional variation in growth and development, giving local and state governments more power than they might imagine to shape economic development and quality of life.8 For example, most decisions about land use policies are made at a local level and they have a tremendous impact on growth, quality of life, and sustainability. States and local units of government also provide many public goods that improve the standard of living, such as parks and schools. Finally, with the devolution of many policy choices from the federal government to states, counties, and cities, state and local governments are now dealing with problems of sustainability and quality of life that the federal government had greater responsibility for in the past.

Investments in Capital Stocks for Sustainable Development

How can local and state governments develop policies that support and improve the overall local standard of living? We believe this begins with (1) valuing all the capital stocks used in producing income, quality of life, and sustainability, and (2) establishing locally based indicators to track changes in these capital stocks and quality of life factors. We first turn to the idea of maintaining capital stocks.

The word capital is usually associated with manufactured equipment owned by private businesses that can produce future output. We use the word capital to describe any stock used to produce goods or services (public or private) that can increase the standard of living.’9 All of these capital stocks are important, as well as interdependent, in creating and sustaining economic development. Some types of capital yield a profit when goods are sold in the marketplace, and that is where private businesses invest their dollars. However, other kinds of capital are provided outside the market by nature, government, or informally by family and community. Along with manufactured equipment, stocks of human skills and talents are necessary for economic output and income. Public infrastructure represents equipment that produces services that do not yield a profit, but are equally needed for economic production and growth. Natural resources are another stock of capital, although unique in that some elements are nonrenewable. All of these are necessary for economic development. There is also the nonmarket value of civic participation and neighborliness that is sometimes called social capital. In addition, technology and innovation are important catalysts of economic growth.

In the “capital stocks” framework, new technologies are embodied in new skills (human capital), new equipment (private business capital or public infrastructure), and new uses of natural resources (natural capital). In addition to maintaining economic production, each of these capital stocks also supports future quality of life and sustainability. Education increases civic participation and influences choices toward lifestyles that are more healthful. Parks provide beauty and wildlife habitat as well as recreation and carbon (CO2) conversion for clean air. Supporting and sustaining all of these are necessary for states and communities to grow and to have true development.

It is important to understand the interrelationship and interdependence of the different capital stocks—natural, manufactured, public, social, and human. Some of these stocks are held privately and some are held in common. For example, some natural resources are private property while others, such as the oceans or the atmosphere, are common property. Businesses own manufactured equipment privately, but infrastructure is shared equipment held in common. What we generally call “human capital” is privately held, but the social capital we discuss in Chapter 3 is a common resource developed and shared by people.10

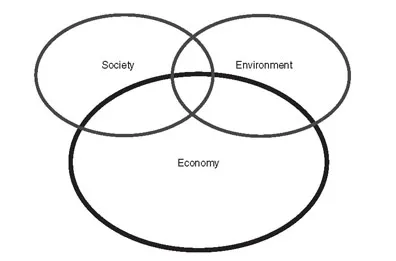

Figure 1.1 The Traditional View: Economy, Environment, and Society

Investment in these capital stocks must be made to serve people and not to serve “the economy.” The purpose of an economy is to serve the needs of people, not the other way around. Economic growth that supports economic development is based on and around people and reflects values and goals throughout the community.

The Economy as Part of the Environment and Society

In putting people at the center of economic development, however, it is important not to lose sight of how the environment supports and encompasses both the economy and society. In the traditional view illustrated above in Figure 1.1, economy, environment, and society are separate, although they have some areas that overlap.

Investments of private capital into the economy are the primary catalyst for wealth creation in the traditional model. Other forms of capital are seen as secondary except when they are used in ways that meet private sector needs. Two examples of this are the value placed on inputs into production such as oil, minerals, or agricultural land and the value placed on attractive environments such as beaches and ski slopes. Similarly, spending on education is often justified in terms of the needs of business for a trained workforce. In contrast, investments that contribute to quality of life or sustainability rather than to increased economic growth are traditionally considered outside the economy and therefore less valuable.

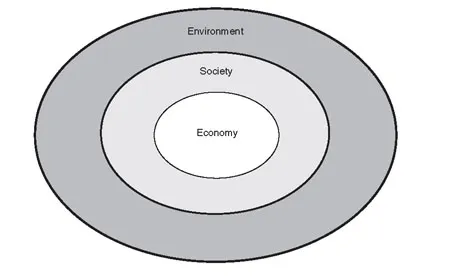

Figure 1.2 Sustainable Development: Economy, Environment, and Society

We think a more accurate representation shows any economy as a subset of society, as in Figure 1.2. Human beings do their first learning in informal units (families), and markets and laws are social relationships established to further their well-being. Human society, in turn, exists with the envelope of atmosphere that is “the environment.” Viewed this way, the synergies between investment in the economy, environment, and society are easier to see and the inevitable trade-offs will be approached differently. We discuss this in greater depth later in the book when we focus on natural capital and the environment, and on human and social capital.

When economic development is equated with simple economic growth, the emphasis is on accommodating the needs of private capital (business) so that it can create growth and jobs. Benefits from economic growth are expected to trickle down to create investments in the other types of capital (human, natural, and infrastructure) that are also needed for production. Our approach to the future of economic development differs in three important ways from the traditional model.

First, we do not accept the trickle-down model as accurate. As we show throughout this book, extraordinary economic growth over the past half century has still left enormous gaps in education, infrastructure, health care, and environmental protection. More economic growth alone will not solve these economic development issues in the future. Second, our approach values all capital stocks for their contributions to quality of life and sustainability of development as well as their contributions to measured economic output and incomes. Third, we take a pragmatic approach on how to best sustain each of these capital stocks. While we believe in relying on market forces that can achieve a socially desired outcome and in avoiding unnecessary bureaucracy and concentration of power, some forms of capital require more public investment than others. An ideology that values small government or low taxes above all else may mean foregoing these investments. In addition, the work of 2009 Nobel prize winners Oliver Williamson and Elinor Ostrom highlights the important role of social cooperation outside of formal governments, as does the work of Bowles and Gintis on social capital that we discuss in our third chapter. Our bottom line is that results are more important than ideology when it comes to sustainable development and quality of life.

The Use of Local Indicators

We mentioned earlier that another important tool for local communities seeking to improve their overall quality of life is locally developed indicators. Currently, economic indicators such as per capita income, housing starts, or the unemplo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Excerpts

- Table of Contents

- Lists of Tables, Figures, and Appendixes

- Foreword by Thomas M. Power

- Preface

- Part 1. Defining Economic Development, Quality of Life, and Sustainability

- Part 2. Creating Sustainable Economic Development for States and Localities

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Authors