![]()

1

What is involved in problem solving

We face problems of one kind or another every day of our lives. Two-year-olds face the problem of how to climb out of their cot unaided. Teenagers face the problem of how to live on less pocket money than all their friends. We have problems thinking what to have for dinner, how to get to Biarritz, what to buy Poppy for Christmas, how to find Mr Right, how to deal with climate change. Problems come in all shapes and sizes, from the small and simple to the large and complex and from the small and complex to the large and simple. Some are discovered: for example, we might discover there is no milk for our breakfast cereal in the morning, or you discover you are surrounded by the enemy. Some are deliberately created: we might wonder how to store energy generated by windmills. Some are deliberately chosen: you might decide to do a Sudoku puzzle or play chess with someone. Some are thrust upon us: in an exam you might find this question, “Humans are essentially irrational. Discuss in no more than 2,000 words.” In some cases, at least, it can be fairly obvious for those with the relevant knowledge and experience what people should do to solve the problem. This book deals with what people actually do.

To help get a handle on the issues involved in studying the psychology of human (and occasionally animal) problem solving, we need a way of defining our terms and classifying problems in ways that would help us see how they are typically dealt with. Historically problem solving has been studied using a variety of methods and from a range of philosophical perspectives. The aim of this chapter is to touch on some of these questions and to explain how this book is structured and the kinds of things you will find in it.

What exactly is a problem?

You are faced with a problem when there is a difference between where you are now (e.g., your vacuum cleaner has stopped sucking) and where you want to be (e.g., you want a clean floor). In each case “where you want to be” is an imagined state that you would like to be in. In other words, a distinguishing feature of a problem is that there is a goal to be reached through some action on your part but how to get there is not immediately obvious.

There are several definitions of a problem and of problem solving. Frensch and Funke (1995, pp. 5–6) provide a list of definitions including very broad ones such as “problem solving is defined as any goal-directed sequence of cognitive operations” (Anderson, 1980, p. 257 – in an early version of his cognitive psychology textbook) and a more restrictive one by Wheatley who states that problem solving is “what you do, when you don’t know what to do” (Wheatley, 1984, p. 1). Anderson’s definitions of problem solving have distinguished between early attempts at solving a problem type and later automated episodes that can still be regarded as problem solving (Anderson, 2000a). For the purposes of this book Wheatley’s definition is closest to what is meant when someone is faced with a problem. However, perhaps a fuller definition might be more appropriate:

A problem arises when a living creature has a goal but does not know how this goal is to be reached. Whenever one cannot go from the given situation to the desired situation simply by action, then there is recourse to thinking … Such thinking has the task of devising some action which may mediate between the existing and the desired situations.

(Duncker, 1945, p. 1)

According to this definition a problem exists when there is an obstacle or a gap between where you are now and where you want to be. “If no obstacle hinders progress toward a goal, attaining the goal is no problem” (Reese, 1994, p. 200). We are not faced with much of a problem when we can use learned behaviours to overcome or get round the blocked goal. In fact, some problems do not have a real block or obstacle. If you speak French and are asked to translate “maman” into English, that is not a problem. Neither is multiplying 4 by 5. If posed questions like those, the responses would be automatic and depend on automatic retrieval processes. We do not need to work anything out. For a different reason, multiplying 48 by 53 is not strictly speaking a problem because the solution involves using a learned procedure or algorithm – we know what we have to do to get the solution (although it would fit into Anderson’s definition as it involves a sequence of cognitive operations). It’s only when you don’t have a ready response and have to take some mediating action to attain a goal that you have a problem (Wheatley’s definition).

Furthermore, for a problem to exist, there needs to be a “felt need” to remove obstacles to a goal (Arlin, 1990). That is, people need to be interested enough to search for a solution, otherwise it’s not a problem for that person in the first place. If we do not have the requisite knowledge to solve a particular type of problem – say, in a domain of knowledge with which we are unfamiliar – then it would not be appropriate to say we have a problem there, either. If I am given a piece of Chinese text to translate into Korean, I would be unable to do it. It is not an appropriate problem for me to try to solve. We would be highly unlikely to be motivated to solve problems that are of no interest or relevance to us. “It is foolish to answer a question that you do not understand. It is sad to work for an end that you do not desire. Such foolish and sad things often happen, in and out of school” (Polya, 1957, p. 6).

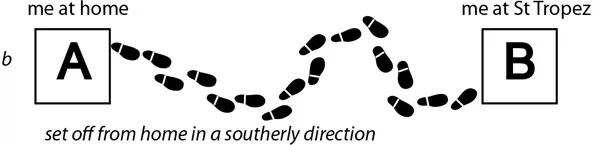

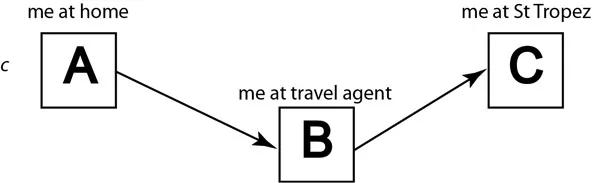

Figure 1.1 illustrates in an abstract form what is involved in a problem and two forms of mediating action. Starting from where I am initially (represented by “A”), one possible action (Figure 1.1b) is to try to take steps along a path seems to lead in the direction of the goal (represented by “B”). This is not a particularly sensible thing to do if your problem is how to get to St Tropez. The second form of mediating action is to do something that will make it easier to get to the goal (Figure 1.1c), in this case perform an action that will lead to a sub-goal (“B”). This is a reasonable thing to do since you will probably get everything you need to know from the travel agent.

Figure 1.1 Representation of problem solving as a blocked goal

As mentioned earlier, “real” problems exist when learned behaviours are not sufficient to solve the problem. Cognitivist and behavioural accounts converge on this view. For example, from the behaviourist side, Davis (1973, p. 12) has stated that “a problem is a stimulus situation for which an organism does not have a ready response.” In discussing cases mainly in the domain of mathematics, where the organism does have a reasonably ready response, Schoenfeld (1983, p. 41) and Bodner (1990, p. 2) have stated that a problem that can be solved using a familiar sequence of steps is an “exercise”. While “exercise” in the realm of mathematics is a useful way of denoting a problem that involves a familiar procedure guaranteed to get a correct answer (an algorithm), it is too restrictive a term to use more generally. Many familiar tasks in our working or domestic environment are algorithmic, but making dinner or decorating a room are not normally classed as exercises even though they involve a sequence of steps that may be very familiar. An exercise tends to involve working forward through a task step by step, as does fixing a flat tyre by a skilled mechanic.

One of the earliest systematic analyses of mathematical problem solving was done by Polya (1957), whose view of the phases of problem solving is shown in Information Box 1.1.

Information Box 1.1 Polya’s (1957) problem solving phases

Polya (1957) listed four problem solving phases which have had a strong influence on subsequent academic and instructional texts. These phases involve a number of cognitive processes which were not always spelled out but which have been teased apart by later researchers. The four phases are:

- First, we have to understand the problem; we have to see clearly what is required.

- Second, we have to see how the various items are connected, how the unknown is linked to the data, in order to obtain the idea of the solution, to make a plan.

- Third, we carry out our plan.

- Fourth, we look back at the completed solution, we review and discuss it.

(p. 5)

While this statement implies a focus on mathematical problem solving – for example, devising a plan means having some idea of the “calculations, computations or constructions we have to perform in order to obtain the unknown” (Polya, 1957, p. 8) – much of what he has said applies to the nature of problem solving in general. The way in which we understand any problem – how we mentally represent it – determines the actions we take to attempt to solve it. Polya also makes the point that problem solving is an iterative process involving false starts and re-representations – we have to work at it, and this, as we shall see in Chapters 7 and 8, can include creative problem solving and insight: “Trying to find the solution, we may repeatedly change our point of view, our way of looking at the problem. We have to shift our position again and again” (Polya, 1957, p. 5). He also pointed out that solving problems from examples or instructions involved learning by doing: “Trying to solve problems, you have to observe and to imitate what other people do when solving problems and, finally, you learn to do problems by doing them” (Polya, 1957, p. 5).

Other phases have been added by later theorists. For example, Hayes (1989) added “finding the problem” to the beginning and “consolidating gains” (learning from the experience via schema induction) at the end (see Chapter 5), and the phases have acquired different labels in some studies such as “orientation, organization, execution, and verification” (Carlson & Bloom, 2005).

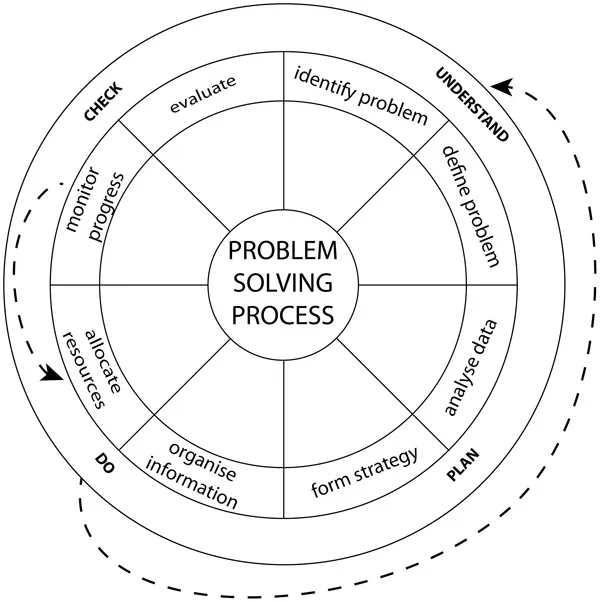

There are many models of the problem solving processes devised principally from Polya’s phases. Figure 1.2 represents a composite view of many such models. The dotted arrows represent the fact that solvers may reach an impasse or encounter constraints that mean they may have to go back to an earlier phase and start again.

Figure 1.2 The problem solving process viewed as cyclical. It is rarely a clear linear process with false starts, dead ends and so forth. For example, as a result of monitoring progress a solver may need to form a new strategy or even re-define the problem and start again.

Where do problems come from?

According to Getzels (1979, p. 168) problems can be presented or discovered or created, “depending on whether the problem already exists, who propounds it, and whether it has a known formulation, known method of solution, or known solution”. A presented problem is simply one that someone or some circumstance presents you with. The teacher gives you homework, the boss asks you to write a report, the weather disrupts your travel plans.

A discovered problem is one you yourself invent or conjure up. “Why is the sky blue?” “How does a microwave oven work?” “Why do burrs stick to my dog’s fur so well?” These are phenomena that already exist, and you have found yourself wondering about them and then trying to determine what is going on. Something that has been irritating you is now reclassified as a problem to be solved, and something that intrigues you leads to a discovery and creative product such as Velcro.

A created problem situation is one that “does not exist at all until someone invents or creates it”. This is the domain of the creative artist, scientist, mathematician, musician and so forth. The individual in this case tries to find a problem to solve in her domain of expertise. A symphony, a Turner prize–winning installation, a theory of the structure of the cosmos are all solutions to problem situations that have been created by the individual.

Whatever the kind of problem we are faced with, we are obliged to use the information available to us, information from memory and whatever information we can glean from the environment we find ourselves in, particularly where that information appears salient – it stands out for some reason. In some cases you don’t know what the answer looks like in advance and you have to find it. You might have a list of things to buy and only a fixed amount of money; do you have enough to buy the things you want? How you find the answer in that example is not particularly relevant; you just need to know what the answer is. In other problems it is precisely how you get the answer that is important: “I have to get this guy into checkmate.” The point of doing exercise problems in textbooks is to learn how to solve problems of a particular type and not just to provide the answers. If the answer was all you were interested in, you could look that up at the back of the book. In cases where you have to prove something, the “something” is given and it is the proof that is important, such as the proof of Fermat’s last theorem.

“Natural” and “unnatural” problems

There are things we find easy to do and others we find hard. Some of this can be explained by the way our environment has shaped our evolution. Within any population there is a degree of variability. Because of this variety there may be some individuals who are better able to cope with novel environments than others. Such individuals have a better chance of surviving and possibly even passing on their genes – including the ones with survival value – to a future generation. Every single one of your ancestors was successful in this respect. None was a failure, because failures don’t survive to produce offspring, and you wouldn’t be here reading this. If our behaviour – including our thinking behaviour – is to be of any use for our survival, evolutionarily ...