- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Illustrated in full color throughout, this delightful collection puts the riches of world mythology at the fingertips of students and storytellers alike. It is a treaury of favorite and little-known tales from Africa, Asia, Europe, the Americas, Australia, and Oceania, gracefully retold and accompanied by fascinating, detailed information on their historic and cultural backgrounds. The introduction provides an informative overview of mythology, its purpose in world cultures, and myth in contemporary society and popular culture. Mythic themes are defined and the often-misunderstood difference between myth and legend explained. Following this, the main sections of the book are arranged thematically, covering The Creation, Death and Rebirth, Myths of Origins, Myths of the Gods, and Myths of Heroes. Each section begins by comparing its theme cross-culturally, explaining similarities and differences in the mthic narratives. Myths from diverse cultures are then presented, introduced, and retold in a highly readable fashion. A bibliography follows each retelling so readers can find more information on the culture, myth, and deities. Character, geographical, and general indexes round out this volume, and a master bibliography facilitates research. For students, storytellers, or anyone interested in the wealth of world mythology, Mythology: Stories and Themes from Around the World provides answers to common research questions, sources for myths, and stories that will delight, inform, and captivate.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mythology for Storytellers by Howard J Sherman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE CREATION

There are as many versions of the story of creation as there are human cultures. Details of the creation vary, of course, according to what aspects each culture finds most important. In some accounts, the world is created from nothing by the will or word of a deity, as in our familiar biblical account, as well as in myths from Egypt, Greece, and Mesoamerica. After the creation, the deity (or deities) may remain the central figure of religious life, as in Judeo-Christian beliefs, or withdraw from humanity, as in the Greek myths.

A related category of cosmic myth is the creation by birth, the world-parent myth. Here two divine parents give birth to the world or to divine or semidivine offspring. Sometimes, as occurs in Greek and Babylonian mythology, the children are forced, for the sake of their own survival or the survival of the newly formed world, to turn against their parents, even to kill them. In a variant form, as in Egyptian and Polynesian myths, the children push their parents, who are sky and earth, apart to make space for humanity.

Another category of creation myth involves the potent mythic symbol: the cosmic ocean. This mythic type, particularly common to Asia and North America, involves a magical being, a bird or an animal, that helps the creator by diving into the ocean and bringing up earth from under the primal waters. In some cases the diver is seen as a subordinate rival to the creator, or even an evil being. In all examples, though, the earth that is recovered from under the waters then expands into the world.

Still another form of cosmic myth involves divine death or sacrifice. In Babylonian myth, for example, the slain Tiamat’s body—she who is a quite literal example of a monster mother—becomes the earth.

Some creation myths reflect the environment surrounding a specific culture. Sumer, lying as it did between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now Iraq, depended on irrigation yet was in constant danger from flooding. Therefore, it is not unexpected to find that water and its control are major elements in Sumerian creation myths. It is the primal sea that is the source of gods and earth. There can be no surprise, then, that the earliest written version of the archetypal flood myth that survives comes from Sumer.

Every culture, not at all unexpectedly, has a myth concerning the creation of humans and animals—indeed, of all living things. The method of creation, though, varies widely. Sometimes, as in the familiar biblical story, humanity comes as much from the will or the word of a creator as from anything physical such as dust. Other myths, such as that of the Babylonians, do hold stronger elements of the physical, telling of humanity sculpted from clay, blood, or other such substances.

Another form of mythological birth is a symbolic one. In myths of this sort, they may tell of the emergence of humanity from a specific sacred tree or rock. Or humanity may emerge from under the earth or from the lower worlds, as in Navajo myths, literally and symbolically from a narrow opening in the earth.

So, for that matter, can gods emerge. The ruler of the Greek pantheon, Zeus, was hidden as a baby in a narrow cave, a cleft in the rocks, in Crete, to protect him from his murderous father, Cronos, who had already eaten his other children. Zeus’ emergence from the cave was clearly a second, symbolic birth; the cave is still revered as a sacred site of fertility.

The rituals of some human cultures echo this symbolism. In Cornwall, until fairly recently, it was considered good fortune to crawl through a natural hole in a rock. And in various initiation customs in shamanistic societies, a budding shaman is ritually “buried” in a cave and must find his way, his “rebirth,” out of that cave.

Eggs, too, can be symbolic of birth, as well as of fertility and even rebirth. African and Chinese myths tell that humanity emerged from the inner to the outer layers of the world egg.

A Polynesian variant shows how the basic template of a myth may be sculpted by local environment, since the world egg is, in this case, replaced by a coconut.

THE BEGINNING OF CREATION

A Myth from Ancient Babylon

Several familiar world themes appear in this myth. The concept of the primal sea is one of the most common, turning up in the myths of cultures as far apart as ancient Egypt, pre-Christian Finland, and the Pacific Northwest of North America. Since our planet is, after all, at least two-thirds covered by water, it’s not difficult to see why so many cultures would have the primal sea concept.

The theme of a divine father wanting to kill his divine offspring also appears in early Greek mythology. See the Greek myth “Theogony” later in this chapter, which takes the theme much further. The fight against a deadly mother figure appears in Aztec mythology as well. The psychological underpinnings of these myths are intriguing, but beyond the scope of this book.

This is the author’s free rendering of various translations of what is customarily known by archaeologists as “the epic of creation” cycle. While the earliest relatively complete versions date to the Old Babylonian era, circa 1900–1800 B.C.E., there is incomplete evidence hinting that other versions may be even earlier.

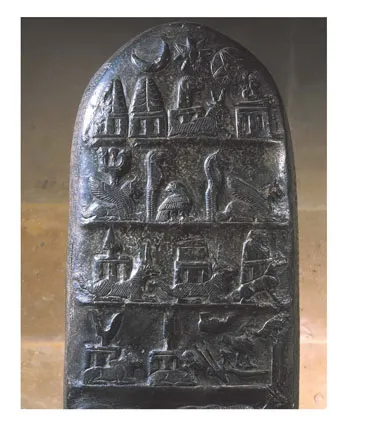

Kudurru of Babylonian king Melishishu II shows emblems of the gods Anu, Enlil, and Ea. Above them are the crescent of the moon god, the star of Ishtar, and the sun of Shamash. At the bottom are a snake and scorpion of the underworld. (Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York)

W hen the sky above had no name, when the earth below had no name, there was Apsu the first, the begetter of all, and there was Tiamat, maker, bearer of all. They mixed their waters together in the primal sea.

There was not yet made pasture or reed, marsh or solid land. They had not yet let gods be manifest.

But gods were born within them. Lahmu and Lahamu they were, their names pronounced as they were fully formed. Then Anshar and Kishar were born as well, surpassing the eldest two. Anshar made his son, Anu, from himself, like himself. And Anu was greater than his begetter, greater than the eldest four.

So it was that more and more gods came into being, and played together in the primal sea. Their noise grew, and the waves that they made while playing disturbed the primal peace.

At last Apsu made complaint to Tiamat. “Their ways are grievous to me. By day I have no rest. By night I have no sleep. I shall destroy them so that we may know peace.”

Tiamat was enraged. “Shall we end what we have formed? Their actions may be noisome, but we should bear it with goodwill. I will not strike against them.”

Apsu was not content. He summoned forth his minister, Mummu, and plotted. “How can we best be rid of the noisy lot?”

Mummu counseled, “Put an end to this here and now. By day you should know rest, by night you should know sleep.”

Apsu was delighted. They plotted evil, he and Mummu against the gods, Apsu’s children.

He did not know that Ea, son of Anshar and cleverest of the young gods, Ea who knew everything, was listening to this deadly plot that Apsu brewed. Ea in his turn fashioned a plan to save the gods. He made an artful master spell, recited it, and brought it restfully upon the waters. Ea’s spell drenched Apsu and Mummu with deepest sleep. Ea bound Mummu as his captive. Then Ea slew Apsu, slew his deadly grandsire.

Now Ea ruled supreme in Apsu’s place, taking on the radiance of royalty. He and Damkina, his wife, dwelled together in quiet splendor. And together they begot a son and called him Marduk. Marduk was a splendid son from birth, a fine and fiery hero god in every way.

But all the while, Tiamat raged in her heart. The waves were troubled as she thought of Apsu’s death, and heard from those children still loyal to her what Ea had done. He had slain her mate. He had taken on the radiance of royalty. She would not have dominion torn from her grasp!

So Tiamat gave birth not to gods but to monsters, an army born of hate. Among them were the horned serpent, the rabid dog, the seething dragon, the hate-filled demon, the raging being half bull and half man, and the loathsome being half man and half fish. Through the veins of each snake in that army ran venom, not blood, and in the eyes of each dragon flashed deadly fire.

“Whoever sees them shall collapse from fear,” Tiamat proclaimed. “Wherever they attack, they shall not retreat.”

Not satisfied yet, Tiamat then raised up one of her offspring, he who is known only as Qingu. Not one description of him is there. But Tiamat was pleased with her creation, so pleased that she took him as her new mate and gave him the army’s leadership.

When news of this most terrible of armies reached Ea, he sat stunned in silence for a time. Then, knowing he must have counsel at once, he hurried to his father, Anshar. But Anshar, looking out at the terror threatening them all, cried out in anger, “It was you who slew Apsu, it is you who enraged Tiamat, and it is you who must declare...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- An Introduction to Mythology

- 1. The Creation

- 2. Myths of Death and Rebirth

- 3. Myths of Origins

- 4. Myths of the Gods

- 5. Myths of the Heroes

- Bibliography

- General Index

- Character Name Index

- Culture Index