- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For courses in Introduction to Archaeology Theory and Methods.Intended for the Introductory Archaeology course with the goal of teaching students how to think like archaeologists, this workbook includes activities that challenge students to interpret and explain field findings and help them to see the link between theory and practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Theory and Practice of Archaeology by Thomas C Patterson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE PROBLEMS

1

STRATIGRAPHY:

ESTABLISHING A SEQUENCE

FROM EXCAVATED

ARCHEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

In order to explain how and why cultural and social forms change through time, archaeologists first have to establish the sequence in which they occurred—that is, which forms were earlier and which ones were later. They can often accomplish this by excavating an archaeological site like the one described in the Introduction. As you recall, archaeological sites are places where there are traces of the activities that someone carried out in the past. Fortunately, some archaeological sites (though certainly not all of them)were formed as a result of multiple occupations—one on top of the other—over an extended period of time. Such sites often refract the complex interplay of the deposition of the traces of human activities, the alteration of these traces through time, and natural processes such as deposition, erosion, or decay (Schiffer 1987; Sharer and Ashmore 2003:236–38). Another way of viewing this archaeological site is that it is a sequence of depositional units that are distinguished from one another by their contents or appearance.

The layering of deposits observed in the archaeological site is called stratification. The individual layers, or strata, may be thick or thin and result from cultural activities, natural processes, or some combination of both (Harris 1975, 1989; Harris, Brown, and Brown 1993; Rowe 1961; Sharer and Ashmore 2003:248–53; Stein 2000). There are two principles of stratigraphy. The first is called the law of superposition, which states that the depositional unit found at the bottom of an undisturbed pile of strata is older than the ones above it. These depositional units would include individual layers of habitation refuse, buildings, graves, and pits. The second principle of stratigraphy is called the law of strata identified by their contents; it says that the depositional units at any particular archaeological site can be distinguished from one another by differences in the various objects and associations they contain, and by differences in the frequencies with which the various cultural materials occur.

The first stratigraphic principle allows us to determine the sequence in which cultural assemblages occur in any given locality; the second allows us to determine what occurred in the sequence, and provides us with a way of correlating or establishing the contemporaneity of cultural assemblages from different localities in the area. These principles were formulated by geologists during the eighteenth century, and were borrowed by archaeologists after they were already established practices in geology, paleontology, and mining.

To establish the sequence at a stratified archaeological site, it is essential to apply both stratigraphic principles at the same time. Noticing that superposition occurs among the depositional units at a particular site has little archaeological significance unless their cultural contents are also observed. If no differences between the cultural contents of two successive depositional units can be observed, then the archaeologists must treat the units as if they are contemporary, even though there is evidence that one unit is, in fact, later than the other. The law of superposition provides information only about the sequence of deposition at a particular locality. Differences in the contents of the various depositional units make it possible to interpret their sequence as a sequence of cultural assemblages.

There are no exceptions to the law of superposition; it has universal application. However, four situations can affect the order of deposition at a given site so that it might not reflect the real archaeological sequence of the locality. First, mixing occurs when a digging operation turns dirt over and leaves it in place, so that the contents of two or more strata occur in the deposit created by the digging. Second, filling occurs when a depositional unit is laid down to alter the original level of the ground; this kind of depositional unit may contain old materials. Third, collection involves the acquisition and reuse of ancient objects, such as jewelry, pottery vessels, grinding stones, or tools. Fourth, unconformities, or temporal breaks, in the stratigraphic sequence of an excavation or site result from a cultural or natural change that caused deposition to cease for an indeterminate time span at that particular locality (Dunbar and Rodgers 1957:116–27; Rowe 1961: 324–26).

Each stratum in a stratified archaeological site has historical significance, in the sense that it refracts one or more events—someone dropped a pot or threw out the trash, there was a seasonal flood, or the village was covered by ash from a volcanic eruption. In another sense, the events recorded by such deposits may in themselves provide relatively little testimony about the social relations that prevailed in those societies. However, the sequence of deposits can provide us with information about how some common category of objects—such as decorated pottery bowls or the form of stone tools—changed from one stratum to the next as undetermined amounts of time passed. Changes in commonly found objects, like pottery, can then be used as a “chronological yardstick” for establishing the temporal sequence of archaeological assemblages in an area.

Stratigraphy provides archaeologists with relative dates—that is, with information about the sequence of the objects and associations, relative to one another. These tell us that the materials from one deposit are older or younger than those from another stratum. They do not tell us how much older or how much younger those materials are; they also do not tell us the absolute age of a particular assemblage, or how long it lasted. To answer these questions, archaeologists must rely on absolute dates, which are typically expressed in terms of some unit of time—such as years, centuries, millennia—and correlated with a calendrical system, usually the Christian calendar. Absolute dates are often obtained by measuring the rates at which natural phenomena occur—the annual growth of tree rings, the disintegration of radioactive carbon in a timber beam, or the formation of argon gas from potassium. Thus, when archaeologists say that a particular assemblage is five thousand years old, they mean that it existed about 3000 B.C. In sum, relative and absolute dates express different things, and they are obtained in different ways.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dunbar, Carl O. and John Rodgers

1957 Principles of Stratigraphy. New York: John Wiley.

Harris, Edward C.

1975 The Stratigraphic Sequence: A Question of Time. World Archaeology, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 109–21.

Harris, Edward C.

1989 Principles of Archaeological Stratigraphy, 2nd ed. San Diego: Academic Press.

Harris, Edward C., Marley R. Brown III, and Gregory J. Brown, editors

1993 Practices of Archaeological Stratigraphy. San Diego: Academic Press.

Rowe, John H.

1961 Stratigraphy and Seriation. American Antiquity, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 324–30.

Schiffer, Michael B.

1987 Formation Processes of the Archaeological Record. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Sharer, Robert J. and Wendy Ashmore

2003 Archaeology: Discovering Our Past, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Stein, Julie K.

2000 Stratigraphy and Archaeological Dating. In It’s About Time: A History of Archaeological Dating in North America, edited by Stephen E. Nash, pp. 14–40. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

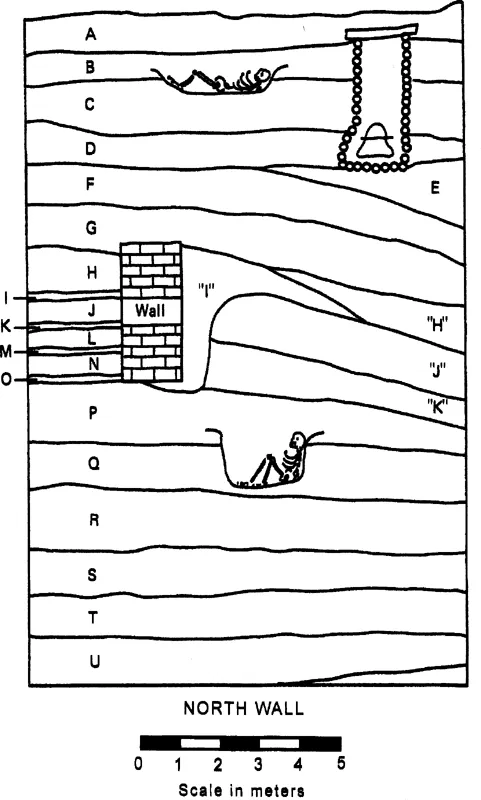

THE DATA AND THE PROBLEM

One way in which archaeologists present visual records of the evidence they uncover is to draw raw profiles of the series of strata that were laid down through time and were exposed during the course of their excavations. Ideally, the profile of each wall, or face, should be illustrated; however, for various reasons, this is rarely the case. Such a profile—the north wall of an excavation—is illustrated in Figure 1, and each of the exposed strata is identified with a letter. It is useful to read these profiles from the bottom up. The archaeologist’s uncertainty at the time of the excavation about the correct chronological sequence of events around the wall in the middle of the profile is indicated by the designation of strata on one side of the wall with one set of letters, for example, Stratum I; and those on the other side of the wall with a second set, for example, Stratum I’. Such designations do not indicate that the strata on the two sides of the wall are contemporary, but rather that they were encountered at roughly the same time during the excavation of this particular block of earth.

The contents of each excavation unit are described separately to ensure that the archaeological associations occurring in each are preserved. The descriptions of the contents of each excavation unit, or stratum, that follow are admittedly inadequate because they contain only information about pottery styles, stone tools, and burial types. The reason for the emphasis in the descriptions is purely for the purpose of the questions to be examined in this section. The reason for this focus on pottery and stone tools is that, when they occur at archaeological sites, they are usually among the most abundant kinds of evidence found; consequently, changes in pottery styles and stone tool types are used to define cultural sequences and to correlate materials found in one area with those that have been discovered in another.

Figure 1

The following descriptions contain information about the chronologically significant features that occur in each of the excavated strata.

Stratum A Red-painted pottery; bottles with red-painted surfaces; shaft tomb with child burial in a vessel with red-painted interior and exterior surfaces.

Stratum B Pottery with circumferential red-painted stripes; bottles with shoulder angles and tapering spouts found throughout the habitation refuse composing the stratum; pit with extended burial dug from the middle of the stratum; burial is associated with one bowl with circumferential red-painted bands and one bowl with punctate and appliqué decoration.

Stratum C Fiber-tempered pottery with circumferential red-painted stripes; straight-sided bottle spouts; bottles with undecorated triangular stirrups.

Stratum D Sand-tempered pottery with circumferential red-painted stripes; straight-sided bottle spouts; bottles with undecorated triangular stirrups.

Stratum E Culturally sterile layer composed of windblown sand.

Stratum F Red-painted pottery; bottles with circumferential red-painted bands on concave-curved spouts.

Stratum G Pottery with red-painted bands; bottles with rounded bot...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- The Problems

- Discussion of the Problems