![]()

PART I

How can we think about young children’s thinking? Concepts and contexts

THE INFANT’S CREATIVE VITALITY, IN PROJECTS OF SELF-DISCOVERY AND SHARED MEANING

How they anticipate school, and make it fruitful

Colwyn Trevarthen and Jonathan Delafield-Butt

Introduction

This chapter presents the child as a creature born with the spirit of an inquisitive and creative human being, seeking understanding of what to do with body and mind in a world of invented possibilities. He or she is intuitively sociable, seeking affectionate relations with companions who are willing to share the pleasure and adventure of doing and knowing with ‘human sense’. Recent research traces signs of the child’s impulses and feelings from before birth, and follows their efforts to master experience through stages of self-creating in enjoyable and hopeful companionship. Sensitive timing of rhythms in action and playful invention show age-related advances of creative vitality as the body and brain grow. Much of shared meaning is understood and played with before a child can benefit from school instruction in a prescribed curriculum of the proper ways to use elaborate symbolic conventions. We begin with the theory of James Mark Baldwin, who observed that infants and young children are instinctive experimenters, repeating experience by imitating their own as well as others’ actions, accommodating to the resources of the shared world and assimilating new experiences as learned ideas for action. We develop a theory of the child’s contribution to cultural learning that may be used to guide practice in early education and care of children in their families and communities and in artificially planned and technically structured modern worlds of bewildering diversity.

Cycles in moving and learning of the human spirit

In 1894 Baldwin published his seminal thesis on psychological development of the infant. He studied the motor development of children to discover the origin of intelligence, and his attention was attracted to the repetition of actions, most obvious at first in limb movements of the young infant, but true of all the infant’s actions, including looking movements of the head and eyes, touching with the hands, and vocalising. He termed this tendency for moving and sensing to repeat itself the ‘circular reaction’:

the self-repeating or ‘circular’ reaction … is seen to be fundamental and to remain the same, as far as structure is concerned, for all motor activity whatever: the only difference between higher and lower function being, that in the higher, certain accumulated adaptations have in time so come to overlie the original reaction, that the conscious state which accompanies it seems to differ per se from the crude imitative consciousness in which it had its beginning.

(Baldwin, 1894, p. 23)

Baldwin claimed that the tendency for an action to be repeated expresses an invariant principle of organisation within human psychological development, which persists in behaviours at every degree of complexity. Baldwin’s circular reactions were the forerunner of Jean Piaget’s sensorimotor and cognitive ‘schemas’ (Piaget, 1962). Both conceived the developing mind as generated in embodied movement. Higher mental functions emerge as abstractions from earlier sensorimotor experience, and are therefore structured by the same principles. Repetition observed in early motor action in infancy, develops into repetition in complex and abstract cognitive thought process in later childhood and adult life. The invariant feature is the tendency for an act, in real movement or in thought, to repeat itself, and for the plan of successfully accomplished acts to be retained and developed through further repetition with variation.

The idea has become a core principle of preschool education theory, originating from the understanding of early childhood gained by the revolutionary educators Comenius, Pestalozzi and Froebel (Athey, 1990; Bruce, 2012). But attention only to object use is insufficient to understand the way a young child learns meanings in human company (Donaldson, 1978). A young child’s action is to be understood in the context of innate capacities for signalling intentions, feelings and experiences to communicate about a shared world, first with parents and family, and then with assistance from companions and teachers in an expanding community (Whalley et al., 2007). The circular reactions of intelligence must be expectant of experiences in relationships, with different degrees of intimacy and reliability.

Baldwin was aware that social collaboration in the making of shared meaning needs circular reactions between the intentions of individuals. He observed the growth of the young child’s self-awareness in engagement with other persons, and their readiness to learn from individuals by attending to the different purposes of their actions. He saw that the principles of repetition in action – ‘accommodation’ to new circumstances in awareness enabling creative novelty, and ‘assimilation’ of successful experience to guide further actions – also regulate and elaborate social habits. He was as interested in changing sociological theory as in advancing developmental psychology in a science of the ‘child and the race’. These ideas influenced George Herbert Mead’s sociological theory of the development of a social ‘Me’ (Mead, 1934) and Jerome Bruner’s psychological theory of development within ‘the culture of education’ (Bruner, 1996). We are built from the start to be attuned social creatures seeking engagement with initiatives and knowledge of other humans. That is how all our cultural habits and achievements are made (Trevarthen and Delafield-Butt, 2013; Trevarthen et al., 2014).

The innate rhythms of experience in the time of action

The existence of a ‘motor image’ formed in the mind, one that anticipates and organises bio-mechanical effects of moving, in the body and in engagement with objects, was firmly established in the 1920s by a young Russian neurophysiologist, Nikolai Bernstein (1967), who used examination of film to accurately trace the regulation of forces in the moving body of a tool-user, a runner, or a child learning to walk. He analysed how the many motor components of any body action are assembled by the dynamic motor image formed in the brain into a coherent, intended movement, which is highly efficient, wasting almost no energy. Bernstein noted that well-done movements are always rhythmic, smoothing out the irregular inertial forces they master through planned steps of time. This power of the brain to integrate its activities in coherent rhythmic patterns is recognised in the philosophy of phenomenology, which admits that motility and consciousness express the brain-generated ‘subjective’ time of intentional doing and thinking (Merleau-Ponty, 1962; Goodrich, 2010). We share an inborn sense of time, and this makes shared doing and thinking or shared meaning possible (Trevarthen and Delafield-Butt, 2013).

The developmental psychobiology of sensorimotor learning

Two lines of research in the last four decades have brought new evidence confirming the generative power of human motives and their timing in self-discovery, and in regulation of relationships.

Careful attention with the aid of film and video recording technology to the capacities and needs of newborns, including those born up to three months before term, has brought to light an intelligence that is expressive in human ways and highly sensitive to the pulse and qualities of human expression, and their tendency to compose narrations (Trevarthen, 2011a). Developments of sensorimotor intelligence in the first three months lead the infant to be a skilled performer in a ‘musicality’ of companionship with a willing partner (Malloch, 1999; Malloch and Trevarthen, 2009). In every human community babies three to four months old begin to enjoy participating in the rituals of traditional action games or baby songs (Trevarthen, 1999, 2006, 2008; Gratier and Trevarthen, 2008; Ekerdal and Merker, 2009) (see Figure 1.4 ).

Newborn infants less than a week old respond to the expressions of other persons and use the imitated actions to establish a dialogue of purposes and experiences (Nagy, 2011). However, in spite of controlled studies by Maratos, Meltzoff, Heimann and others that prove the infants can imitate, this is a highly controversial area of research, because the findings contradict long-held beliefs and rational arguments that an infant can have no intentional self that is conscious of an outside reality for weeks or months after birth, and no ability to perceive the actions of another person as like those of a self (Kugiumtzakis and Trevarthen, 2014).

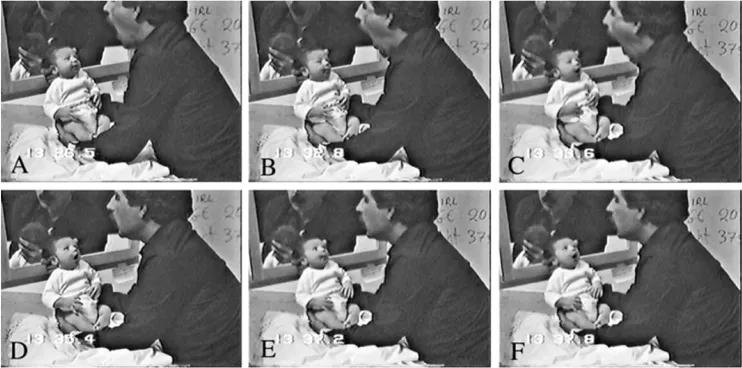

Detailed study of videos of interactions with full-term and premature infants in the first days after birth shows a baby can focus attention and imitate movements of head, eyes, and mouth, with parts of their own body they cannot see, and even try to imitate simple sequences of vocal utterances (Figure 1.1). Emese Nagy with Peter Molnár (2004) made an important modification of the testing procedure by waiting for a few seconds after the newborn infant has imitated her, which evokes a repetition of the imitated act by the baby as a ‘provocation’ for a response from the adult. Concurrent recording of heart rate changes showed that while ‘imitation’ is associated with effort signalled by heartbeat acceleration, ‘provocation’ is accompanied by a slowing of the heart, indicative of focused attention for a response.

Imitations of a newborn infant are the product of nine months of development in brain and body. Research tracing the first stages of the conception of a human being reveals a time-regulated process of collaboration between living elements (Delafield-Butt and Trevarthen, 2013).

The human foetus at eight weeks has distinctive body form with adaptations of hands, hearing organs, eyes, mouth and vocal organs that show anticipation of a life in conversation (Trevarthen, 2001). At this stage the subcortical brain, that will be the integrator of intrinsic motives for sensory-motor functions of the whole, and for emotional appraisal of objects of action is forming in close relation to the systems that regulate hormonal functions of the vital self:

The first integrative pathways of the brain are in the core of the brain stem and midbrain, and the earliest whole body movements, though undifferentiated in their goals, are coherent and rhythmic in time. When sensory input develops, there is evidence, not just of reflex response to stimuli, but of the intrinsic generation of prospective control of more individuated actions, before the neocortex is functional. In the third trimester of gestation, when the cerebral neocortex is beginning formation of functional networks, movements show guidance by touch, by taste and by responses to the sounds of the mother’s voice, with learning.

(Delafield-Butt and Trevarthen, 2013, p. 205)

The origin of the mental life of a child is identified at this time, at 50 days’ gestational age, as the integrated neuromotor system enacts the first spontaneous circular reactions of the organism (Delafield-Butt and Gangopadhyay, 2013).

Movies made by ultrasound, which enable sight of the foetus alive in the mother’s body and the measurement of activities, confirm that from mid-gestation limb movements of the foetus are purposefully guided, anticipating sensory feedback, and experimenting with it. These self-regulating movements not only show differences of vitality that identify different foetuses as more or less animated personalities, even in ‘identical’ twins (Piontelli, 2010). They also reveal a special sensibility for the presence of an ‘other’, reaching and touching with special care towards a twin. Facial expressions show that the foetuses have emotions of pleasure in appreciation of ‘good’ tastes or physical sensations, and of anxiety or disgust for ‘bad’ experiences. Hearing develops in the last months and the mother’s distinctive voice is recognised by the newborn to identify her as a preferred partner. This helps the baby learn her face in the first days.

Figure 1.1 A cycle of imitations of Mouth Opening with a female infant 20 minutes after birth. Recorded at a maternity hospital in Herakleion, Crete in 1983 by Giannis Kugiumutzakis for his PhD research at the University of Uppsala (Kugiumutzakis and Trevarthen, 2014). A (0 sec...