- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Interior Architecture Theory Reader

About this book

The Interior Architecture Theory Reader presents a global compilation that collectively and specifically defines interior architecture. Diverse views and comparative resources for interior architecture students, educators, scholars, and practitioners are needed to develop a proper canon for this young discipline. As a theoretical survey of interior architecture, the book examines theory, history, and production to embrace a full range of interior identities in architecture, interior design, digital fabrication, and spatial installation. Authored by leading educators, theorists, and practitioners, fifty chapters refine and expand the discourse surrounding interior architecture.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part one

Histories

Chapter 1

(Re)constructing histories

A brief historiography of interior architecture

I began my academic career in 1999 as a lecturer in what was, at the time, a relatively new subject: interior architecture. There was little for students, or for me, to read about interior architecture. The only comprehensive work of which I knew was John Kurtich’s Interior Architecture published in 1995. Since that time, however, there has been something of a publishing explosion around the subject.1

This chapter critiques some of this literature and charts the theorization of the subject since the late 1990s. In addition to Kurtich’s foundational text, this chapter discusses John Pile’s History of Interior Design (2000), Graeme Brooker and Sally Stone’s Re-readings (2004), Fred Scott’s On Altering Architecture (2008), Penny Sparke’s The Modern Interior (2008), and Charles Rice’s The Emergence of the Interior (2007).2 Not all of these books are explicitly about interior architecture. Scott, Brooker, and Stone, for example, addressed an audience of architects and interior designers (Re-readings being published by RIBA). Pile, Rice, and Sparke focused on interior design and a more academic audience. All of them contributed significantly to discussions surrounding the new discipline. While books by Pile, Sparke, and Rice are strictly histories, Scott offers a theoretical disquisition; Brooker, Stone, and Kurtich deliver compendia of case studies. In each, however, a sense of history informs understandings about what interior architecture was, is, and could become.

How, then, were these histories of interior architecture constructed? What were their roots and precedents? Why were these books written when they were written? What did they conceive themselves as being histories of? What evidence did they use, and how was it welded into narratives? This chapter will specifically address these historical and historicized understandings of the discipline. It provides a lens through which the identity of interior architecture was constructed during this period. It attempts to show how history is not merely the record of things past, but, like interior architecture itself, a (re)construction of preexisting structures.

Why were these books written?

The turn of the twenty-first century was a time when one important aspect of interior architecture – the reuse of existing buildings – emerged in the form of Grands Projets like the Tate Modern (Herzog and De Meuron, 2000) and Berlin Reichstag (Norman Foster, 1999) to occupy the center ground in architecture. John Kurtich put it somewhat messianically:

The emergence of interior architecture as a new profession is an idea whose time has come. It is the link between art, architecture, and interior design. The professionals in this area have created this term to express a humanistic approach toward the completion of interior spaces. This approach, shared by many design professionals, has begun to produce a definition that is distinct from current practice.3

Fred Scott was more modest, commenting, “That theory follows in the wake of the expedient.”4 There were, however, other agendas at work. Scott continued:

This book began from a partisan argument for the contribution of art school designers to be recognized as being valid in the alteration of the built environment as the more celebrated work of architects in making new buildings. It was, in the beginning, an argument against a widely assumed hegemony.5

The works under discussion here were not written by architects but by studio teachers in art schools, such as Scott or Graeme Brooker, and theoreticians and historians of design, such as Sparke, Rice, and Pile. There was a political and professional dimension to their efforts. “Designers disdained the elitist architects for their compulsion for purity and maintenance of concept. Architects generally considered designers to be frivolous with no philosophical base of knowledge to guide their work,” explained Kurtich, but as Scott hinted, architecture was perceived to have a hegemony that design did not possess.6

Graeme Brooker and Sally Stone’s Re-readings connected the emergence of interior architecture to postmodernism, though not the stylistic postmodernism of the 1980s. “The rise in the number of buildings being remodeled, and the gradual acceptance and respectability of the practice, is based on the reaction to what is perceived as the detrimental erosion of the city and its contents by modern architecture.”7 The very title of their book suggested a nod to literary postmodernism. “Many examples of modernist architecture,” they wrote, “were the product of a formal system that was essentially self-sufficient,” while the alteration of buildings offered opportunities to explore the aesthetics of the incomplete, the incoherent, and the layered.8 Books about interior architecture arose, their authors claimed, in response to three main stimuli: the increasing volume of the practice on the ground, a long-standing political conflict taking place between the professions of interior design and architecture, and a “second wave” of postmodern practice and theory.

What were these books about?

Having identified the existence of a new practice, Kurtich divided it into three practices:

First, it can be the entire building designed as an external shell containing integrated and finished interiors. Second, interior architecture can be the completion of space within an existing architectural enclosure. Finally, it can be the preservation, renovation, or adaptive reuse of buildings, historic or otherwise.9

His book addressed itself to “architectural masterpieces from various historical periods,” including “well known modern examples,” and he felt the need to point out, “the examples presented are not limited to interiors.”10

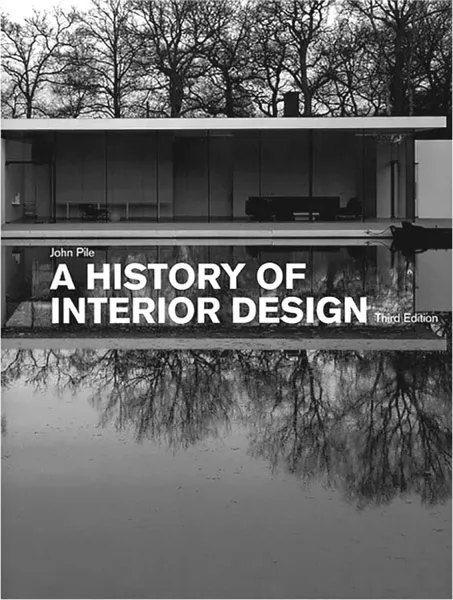

Pile’s history was conceived as a primer – a sort of Pevsner or Bannister Fletcher for interior design. “Professional interior designers,” he wrote, “are expected … [to] know the practices of the past in terms of ‘styles’ … the purpose of this book is to deliver in one volume of reasonable size, a basic survey of 60,000 years of personal and public space.”11 The word space is key, for while Pile’s history is ostensibly a history of interior design, it takes an architectural approach to its subject:

interior design is inextricably linked to architecture and can only be studied within an architectural context … Enclosed spaces such as ruins, ancient sites, and open courtyards are given due consideration even though the sky may be their only ceiling and they are, therefore, not strictly interiors12

At the same time, references to the other elements that comprise the interior – furniture, textiles, and so on – were limited to edited highlights.13

Penny Sparke contributes to the discussion from a different perspective. Her starting point was Walter Benjamin’s famous comment on Paris of the nineteenth century:

for the private individual, the place of dwelling is for the first time opposed to the place of work. The former constitutes itself as the interior. Its complement is the office. The private individual, who in the office has to deal with reality, needs the domestic interior to sustain him in his illusions.14

Sparke continues to suggest that the modern interior has been formed out of the opposition between “two spheres”: the domestic interior, characterized by femininity, soft textiles, practices of decoration, and so on, and the public interior, characterized by hard surfaces and materials, male occupations, and architecture. “The boundaries between the ‘separate spheres’ were fundamentally unstable, and it was that instability, rather than the separation per se, that, I will suggest, defined modernity, and by extension the modern interior.” Her history documents episodes in this long-running boundary war: in the domestication of the public spaces of the hotel and café in the nineteenth century, for example, or the victory of the architectural interior in the Gesamtkunstwerk homes of the early twentieth century. “Art School” interior design – a sort of soft modernism was, she concluded, a sort of resolution between the two spheres that proved temporary by the current rise of interior architecture.

Figure 1.1 The modern interior as architecture: the cover of John Pile’s History of Interior Design (2009 Edition)

Image credit: Wiley

Figure 1.2 The modern interior as domestic occupation: the cover of Penny Sparke’s The Modern Interior (2008)

Image credit: Reaktion Books

What evidence did they use?

Sparke identified the interior as an unstable category, and even Pile, whose history of the interior is the most “architectural” discussed here, was forced to admit,

Interiors do not exist in isolation in the way that a painting or a sculpture does, but within some kind of shell … they are also crammed with a great range of objects and artifacts … this means that interior design is a field with unclear boundaries.”15

Those boundaries are temporal, as well as spatial. “Interiors,” Sparke argued, “are rendered even harder to discuss by the fact that they are constantly being modified as life goes on within them.”16 Sparke was referring to domestic interiors, but the comment has implications for any understanding of the history of interior architecture. An altered building is only ever in a temporary state, destined to be obliterated by history just like the decorative schemes of ephemeral homes. Nevertheless, Pile’s history presents interiors as if they possessed such clear boundaries. Interiors are predominantly depicted through photographs, as objects (albeit inside-out ones) largely denuded of that “great range of objects”17 he mentions in his introduction. The construction of these images is not discussed, as if they were transparent evidence of the interiors depicted.

In The Emergence of the Interior, Charles Rice disagreed with this approach: “Visual representations of interiors are not simply transparent to spatial referents, even if such spatial referents exist; representations construct interiors on a two-dimensional surface as much as practices of decoration and furnishing construct interiors spatially.”18 Furthermore, he argued the lens through which such images are constructed is in itself a temporary phenomenon:

The Oxford English dictionary records the “interior” had come into use from the late fifteenth century to mean inside as divided from outside, and to describe the spiritual and inner nature of the self and the soul. From the early eighteenth century, “interiority” was used to designate interior character and a sense of individual subjectivity, and from the idle of the eighteenth century the interior came to designate the domestic affairs of a state, as well as the territory that belongs to a country or region. It was only from the beginning of the nineteenth century, however, that the interior came to mean “the inside of a building or room.”19

To compound the problem, the term “interior architecture” itself did not widely come into exis...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part one: Histories

- Part two: Territories

- Part three: Spatialities

- Part four: Sensorialities

- Part five: Temporalities

- Part six: Materialities

- Part seven: Occupancies

- Part eight: Appropriations

- Part nine: Geographies

- Part ten: Epilogue

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Interior Architecture Theory Reader by Gregory Marinic in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.