eBook - ePub

Treating Complex Trauma and Dissociation

A Practical Guide to Navigating Therapeutic Challenges

- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Treating Complex Trauma and Dissociation

A Practical Guide to Navigating Therapeutic Challenges

About this book

Treating Complex Trauma and Dissociation is the ideal guide for the front-line clinician whose clients come in with histories of trauma, abuse, self-injury, flashbacks, suicidal behavior, and more. The book helps clinicians develop their own responses and practical solutions to common questions, including "How do I handle this?" "What do I say?" and "What can I do?" Treating Complex Trauma and Dissociation is the book clinicians will want to pick up when they're stuck and is a handy reference that provides the tools needed to deal with difficult issues in therapy. It is supportive and respectful of both therapist and client, and, most of all, useful in the office.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Treating Complex Trauma and Dissociation by Lynette S. Danylchuk, Kevin J. Connors in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Understanding Complex Trauma and Dissociation

1The Meaning and Impact of Complex Interpersonal Trauma

They come for help appearing anxious, in pain, angry, or seemingly fine. Your heart goes out to them and you know you’ll do everything you can to help. However, helping is not that easy. There’s more to this person than you can possibly see at the first meeting, or in the several that follow.

Trauma layered upon trauma creates a burden that can make it hard to live, hard to work, and hard to trust. Therapy, built upon a foundation of trust and emotionally intimate dialogue, can become stymied in a swamp of mistrust; challenging the very fabric of the therapeutic relationship. Still, there’s a spark of life and hope that has this person seeking something better, trying to heal.

In order to help traumatized people heal, the clinician needs to learn about trauma and about the individual who has come for help. That sounds obvious, but it’s not unusual for treatment to start with no sense of the client’s history. More and more, people are learning to wonder what happened to a person rather than immediately judging what is wrong with that person. The recent movement to trauma-informed care has been very helpful in creating an environment of respect for the client and an assumption that behavior may be more of a reflection of the person’s trauma history than any kind of flawed personality. The shift in perspective is a breath of fresh air in this field, felt by clients and all those who help them.

The behavior does not define the person. However the behavior often expresses what the person feels but cannot say. When language is insufficient or unsafe, their actions tell us what hardships they wrestle with, what crosses they bear.

Every client comes from a context, a family, life situation, and culture. People naturally adapt to the situation in which they are born in order to survive. If it’s a good situation, healthy and safe, the person can focus on growth and actualization. If the situation is negative, the person will need to adapt, using his or her energy to survive, developing coping mechanisms and missing out partially or completely on developmental stages. It takes a lot to live through traumatizing experiences, and the time and energy devoted to working with trauma diverts that person from working in many other areas of life. There’s often little or no time to play, to develop social skills based on trust, and to feel free to explore the world.

In therapy, behavioral problems emerge. It’s inevitable, because the person has been traumatized, and if that trauma has gone on for a long time, that person has not had the opportunity to learn healthy emotional regulation and social exchange. Their patterns and defenses are strong because they’ve needed to be strong. Changing those patterns is possible, but difficult, like rebuilding the foundation of a house while still living in it.

Too often, the client’s behavior has become a negative label, the person is identified as the label, and treatment becomes focused on managing their behaviors by controlling superficial symptoms. Because the behavior can be chaotic or dangerous, this approach is understandable, and the client may welcome the attempts to control symptoms. However, if symptom management is all that is being done in therapy, true healing may never happen. People with identity problems will often take on the label—it will stick.

For example, a client who came in with the diagnosis of obsessive compulsive disorder. She got that label because of her need to check and re-check the locks on her doors and windows before going to sleep at night. No one had asked her about her life history. If they had, they would have discovered she’d been kidnapped from her home. It was immediately obvious that this behavior was motivated by trauma, by the desire to stay safe, and not by an obsessive compulsive disorder.

Another client presented with a history of treatment failures marked by her case file being three 3 inch thick binders documenting her struggles in every imaginable kind of group therapy process. Typical of cases like this, she had multiple diagnoses including major depression, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and oppositional and defiant. Throughout her long career with the treating organization, no one had bothered to ask about her history. No one had explored the conflicts and betrayals she had experienced in all major relationships prior to entering therapy.

Complicating the therapeutic relationship were her dissociative defenses: dissociative amnesia, depersonalization, derealization, and dissociative trance states that were the hallmark of her coping with intense affect or conflict. As she withdrew into herself in the face of triggering group content, she became quietly less and less responsive. The group facilitator would then ask her to leave at the end of the session, angry at her “blatant disregard of the boundaries of the group setting.” The therapist perceived her as a problem client, unwilling to accept the structure and rules of the group. She saw the therapist as another in a long line of disappointed and angry authority figures. Worse still, these dysfunctional interactions confirmed, for her, her identity as a failure.

Behaviors do not emerge from a vacuum. They almost always represent a person’s attempt to deal with his or her environment. For example, people learn to be manipulative if asking for what they want or need results in deprivation or abuse. Having learned that the direct path leads to failure, they learn to use an indirect path. Another example is the tendency to escalate into crisis. Having learned that the only way out of crisis is to go through it, people may actually push for crisis in order to be done with it. That looks counterproductive to many people on the outside, but makes perfect sense in the context of the person’s life. Asking about the client’s history, his or her experiences at home, school, and other places, helps the therapist understand how the behavior may have functioned to help the person sometime in the past.

If the client has been severely traumatized or hurt fairly consistently over a long period of time, asking about his or her history may not immediately provide much information. The client may not remember or be able to share what is remembered. There may be disruptions in memory, amnesia, and/or avoidance because the trauma is too painful to face. That does not mean the client is ‘resisting,’ but means that the client’s defenses are protecting him or her against overwhelming affect. Nor does it mean that the client won’t trust the therapist. The client has no reason to trust the therapist until trust has been developed between them. With betrayal such a common experience for trauma survivors, that trust may take a very long time to grow.

It is not uncommon for people with multiple traumas to have dissociative issues of varying kinds. Dissociation may serve as a circuit breaker for emotions that are too intense to feel, or it may have evolved into a way of being in the world, or both. Over the course of work with a client, you may see patterns of conflicting and confusing behaviors, a client who may shift from angry and shaming, to frightened and frozen, alternately erudite and intellectually challenging, then quiet, and seemingly able to understand only the most concrete language. Multiple symptoms may include eating disorders, substance abuse, domestic violence, and self-harming behaviors. All of these things may have dissociative elements that will need to be addressed.

Most mental health practitioners are not trained to identify complex trauma and dissociation in their clients. If they do know about dissociation, they may only think of the most extreme form of that, Dissociative Identity Disorder, perceive that to be rare, and miss the signs of that and milder forms of dissociation in the clients they see.

When the clinician has a comprehensive understanding of trauma-based disorders and dissociative defenses, the potential outcome of therapy improves, and more clients get better.

The awareness that trauma impacts people has been around for a long time. Back in 1916, Freud described psychic trauma as

An experience which within a short period of time presents the mind with an increase of stimulus too powerful to be dealt with or worked off in the normal way, and thus must result in permanent disturbances of the manner in which energy operates.

(Freud, 1916)

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Complex Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

A single trauma can have a devastating effect on a child, or an adult. However, with single trauma, there’s a sense of ‘before’ and ‘after,’ and the shift from pre-trauma to post-trauma is often recognizable to all. Acute stress disorder (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5, 2013) symptomatology is a relatively normal and understandable response to a traumatic experience. If the symptoms persist past one month, the person is said to be suffering from Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

In PTSD, the client’s phenomenological presentation shows them alternating between a state of extreme arousal marked by hypervigilance, irritability, and pronounced startle reactions and a state of withdrawal and numbing marked by flat or blunted affect, social isolation, and constricted behaviors. These alternating defensive behaviors are often exacerbated by intrusive ‘flashbacks’ or profound invasive episodes where past memories are recalled with such cognitive, emotional, and sensory strength as to challenge current reality testing and leave the client unsure and unsettled as to where and when is here and now. The physiological, neurological, endocrinological, and psychological elements of this disorder make an uncontrollable and unbearable impact on our client’s lives, relationships and sense of self.

With the accumulation of traumas, however, the impact becomes complex, and there may not be a ‘before’ sense of self that can be identified. Consider what happens when the trauma is ongoing, for years. Imagine the abuse starting when the child is most vulnerable and just entering into the crucial periods in psychosocial development. Consider what happens when the perpetrator is someone within a close personal, emotionally intimate relationship with the client.

How does this impact the child’s emerging sense of self? How might this inform the child as to the nature and meaning of interpersonal relationships, the value of engaging in emotionally open, vulnerable and trusting relationships? What intrapsychic defenses might be needed to cope with the sense of overwhelm?

The resultant cacophony of discordant emotions, intense, unmitigated emotional responses, manipulative behaviors, combined with a pervasive sense of mistrust, shame, and powerlessness is the hallmark presentation of the survivor of complex trauma disorders.

A series of traumatic incidents results in complex trauma, but the symptoms of complex trauma can also develop from an insufficient environment coupled with a single trauma. An insufficient environment may mean an inadequate attachment, an unsafe environment such as a dangerous neighborhood or proximity to war, or a background of relatively mild abuse prior to a major trauma. In these cases, the person is already on shaky ground emotionally, and a single trauma can be far too much to handle, causing the person to collapse.

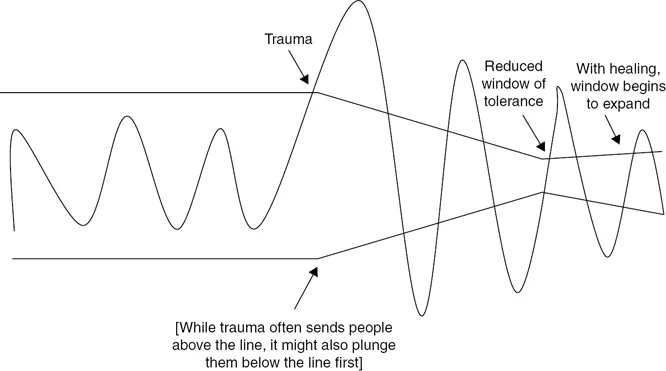

What happens to people during trauma? What Freud describes as “stimulus too powerful to be dealt with” translates into what Daniel Siegel describes as outside the person’s ‘Window of Tolerance,’ beyond the person’s ability to manage, tolerate, emotionally (Siegel, 2001). The person becomes hyperaroused, with unbearably intense emotions, or hypoaroused, deeply depressed, without emotion. The Window of Tolerance represents the levels of intensity, high and low, that can be tolerated by a person, levels within which the person feels able to respond and be in control of himself or herself (Figure 1.1). People learn their limits, and they will stay within them if at all possible.

Figure 1.1 Window of Tolerance

Trauma either sends a person over the line, with the emotions so intense they can feel out of control, or below the line, where the intensity drops out, leaving the person deadened, devoid of emotion. Typically, the traumatized person swings between extremes, from hyper to hypoaroused, going through waves of ups and downs, which gradually decrease over time. While in this traumatized place, the person becomes less able to tolerate new incoming stimuli. Already in overwhelm, not much more can be taken in or dealt with adequately. Simple, ordinary frustrations or difficulties feel like overwhelming crises, and the person can’t handle them in normal ways. As the person heals, the waves of emotion subside, and if the person heals well, the ability to tolerate emotional intensity will increase. Post-traumatic growth is possible, with greater ability to tolerate higher and lower levels of emotional intensity and stay conscious and present. Without healing, however, the Window of Tolerance may remain small, resulting in an inability to deal with intense emotions that come after the trauma.

Developmental Trauma

“Permanent disturbances in the manner in which energy operates” (Freud, 1916) can be another way of describing developmental trauma. The normal development of a child is disrupted because of the overwhelming energy of trauma and the need to survive in hostile environments.

Trauma also affects the cognitive-behavioral developmental concepts of assimilation and accommodation (Piaget, 1952). Piaget describes how infants and children develop from innate reflexes to intentional actions. When all goes well, the child moves from simple instinctual or random experiences into sequenced patterns of behavior aimed at getting needs met.

A key element of Jean Piaget’s theory of the cognitive development of the child is the focus on the child’s endeavor to understand and master the world around him/her. The child’s developing sense of understanding can be expressed as increasingly a complex series of rules, operations and schemata.

Assimilation refers to the process of integrating new information, new behaviors, and new understanding into the existing ideas, behaviors, and coping strategies while reinforcing these current cognitive schema. For example, little Kevin learns to open the door to his bedroom by twisting a knob. He...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part 1 Understanding Complex Trauma and Dissociation

- Part 2 Treatment

- Part 3 Complicating Factors—Heads Up—The Person You Will Be Treating Comes With More Than You Know

- Part 4 The Trauma Therapist

- Links

- References

- Index