![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

To learn about the view camera, you must first understand what a camera is.

WHAT IS A CAMERA?

For an object to be labeled accurately a camera, it must have certain basic parts. Common to all cameras is the lighttight body that supports the other parts and prevents unwanted light from striking the film. Integrated into the body is a provision for inserting, holding in place, and removing the film. A lens and shutter admit and control the light, a focusing system adjusts the distance between lens and film, and a viewing system allows you to point the rest of the parts in the right direction. These basic parts are present in the simplest snapshooter (although the focus is often fixed), in the most complex 35mm SLR, and in every view camera.

What Is a View Camera?

A view camera shares its essential anatomy with all cameras, but no other camera type reveals itself as clearly. The view camera’s functional skeleton is on display without decorative covering and none of its basic operating features is obscured by automation. Using the view camera will give you an appreciation and understanding of the bare bones of photographic practice—the fundamentals of making photographs. We will take advantage of this revealed anatomy by using as our model a modular view camera so that we may inspect each part, feature, and application separately.

The modern view camera is a complex and sophisticated system, but it can be broken down into modules, each of which is an individual camera part. Each part is an elemental building block that is interchangeable with other versions of the same part; each can be used to assemble and rearrange the camera for a variety of photographic tasks. Since an understanding of these elements is necessary to the proper use of any view camera, Chapter 2 describes the parts of a modular monorail view camera. Details on the rest of the large-format camera family are presented in Chapter 6, after a complete explanation of how to use the monorail camera and the chapters on the lens and film systems common to all large-format cameras. If you are using a camera other than a monorail, you may wish to read the appropriate section of Chapter 6 immediately after you read Chapter 2.

A modern modular monorail camera like this Swiss Sinar has a range of interchangeable parts and accessories to help overcome nearly any photographic challenge. ■

WHY USE A VIEW CAMERA?

View cameras are heavier, bulkier, and more obtrusive than smaller-format cameras, it is time-consuming to set up and use them, and the camera, film, and accessories can be expensive. There must be some considerable advantages to outweigh all of these drawbacks.

Indeed, two important characteristics influence many photographers to use no other camera. First, large-format film renders an image with the highest possible visual quality. All the common measures of photographic excellence—sharpness, resolution, tonality, and color saturation—increase with film size. And second, a view camera offers more control over perspective and focus than any other kind of camera. By adjusting the independent front and back of the camera, you can rearrange the position of the vanishing point and the location of the sharpest focus. These advantages would not persuade a photojournalist to use a view camera; to capture the news, a photographer must be unencumbered—free enough and fast enough to follow the action. But for the photographer of the landscape, a captive subject that waits patiently for the most flattering light, there is time to set up and use a camera that can deliver the highest possible quality.

The view camera is often considered a professional photographer’s tool. Architectural photography, a specialized but well-populated field, demands the control over perspective available only to the user of a view camera. The studio of an advertising, commercial, or portrait photographer is another natural habitat for the view camera. In the studio, everything is arranged for the benefit of the photograph: the scene is assembled, the lighting manipulated, and the moment of exposure selected. After all that, the additional time necessary to set up and use a large camera is slight. The studio photographer leaves nothing in the photograph to chance, and the client who pays for all the care deserves (and usually demands) the superlative quality of an image made on large-format film.

Paradoxically, even the seemingly undesirable characteristics of the view camera are often virtues. Its slow, cumbersome nature forces the photographer to pay close attention to details. Because the entire frame must be studied while focusing, careful composition takes little more time than casual use; the pace encourages care. There are few unpleasant surprises on the processed film. This way of working prompted photographer and art historian Carl Chiarenza to write of the magic of the ground-glass image for the creative photographer:

The view camera photographer is forced into a contemplative mood while he works. Seen in this light the disadvantage of bulky equipment and accessories such as tripods becomes an advantage. It sets the pace for the seclusion under the dark cloth. Facing the ground glass, isolated, all of his facilities are centered on the luminous image. He cannot help being absorbed by the many possible relations he can create within the movable frame. He loses himself in this world of light over which he can exercise a measure of control.

Sometimes the conspicuous use of a view camera enables photographers to make pictures that would not have been available to the user of a hand camera. Bruce Davidson, making the photographs for his landmark book East 100th Street, chose a 4×5 camera specifically for its cumbersome nature and obtrusive appearance. Working in a poor African-American and Hispanic neighborhood where a stealthy photographer, especially a Caucasian, would be suspect, he chose equipment that would announce his presence and serious intent. “Every day I appeared with my large bellows camera, heavy tripod and box of pictures. Like the TV repairman or organ grinder, I appeared and became part of the street life.” The view camera photographer is never taken for an amateur.

You probably already have a reason for learning about the view camera. If not, the unique merits of large-format photography with a view camera will make themselves apparent soon after you make your first exposure.

Trees, Montara. Made electronically in 1994 with a Dicomed Digital Insert in a conventional 4×5 camera, this image shows one startling advantage of direct digital photographs—the capacity to record a much wider range of brightness values (dynamic range) than film. Photographer Stephen Johnson also made effective use of the extended infrared sensitivity of the recording sensors and emphasized the surreal tonalities by using only the red channel of the RGB file. ■

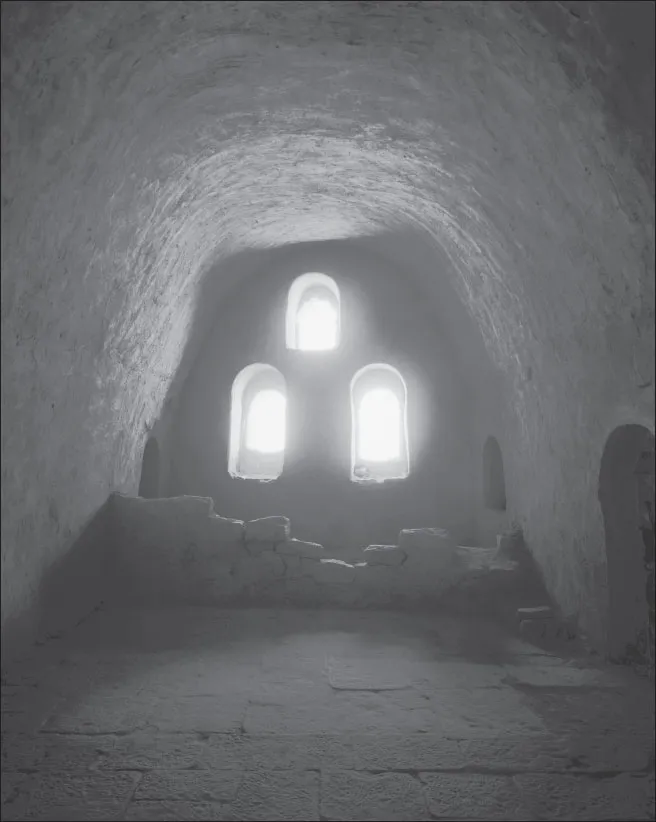

Coptic Monastery, 1989. Linda Connor has traveled the world with her wooden 8×10 camera making reverential, mystical photographs. The large negative lets her produce exhibition prints outdoors in her sunny back yard by contact printing onto slow printing-out paper. She later gold-tones the prints to achieve a luminosity and color range beyond those of enlarging materials. ■

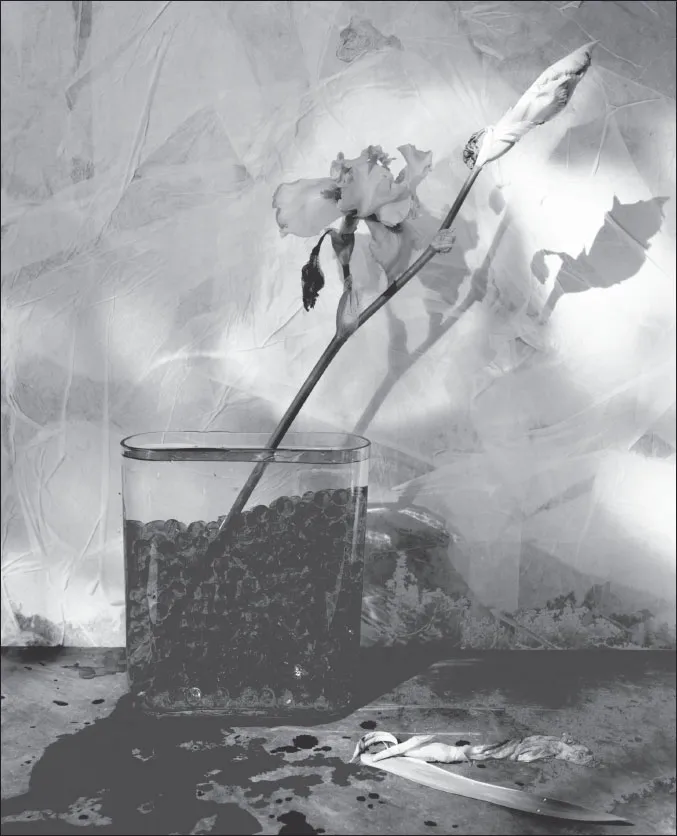

Iris, 1991. Robert J. Steinberg scanned his 11×14 original negative for this image in order to generate digitally a larger (30×40 inches) negative with the correct tonal qualities for platinum printing. For non-silver processes that require contact printing, making a bigger negative by traditional enlargement unavoidably compresses delicate highlight and shadow tones. ■

![]()

2

THE CAMERA

Large-format cameras are categorized by two important features: their format, or nominal film size, and their design. The film size in a camera’s designation is usually the largest conventional rectangle the camera can accommodate. These dimensions are given in inches for the United States and United Kingdom and in centimeters for countries that use the metric system. All large-format cameras can be adapted to the use of smaller film, so the nominal film size indicates only the upper limit. A 4×5 camera (called 5×4 in Britain and 10×12 in Germany) can use any size film up to 4-inch by 5-inch film sheets. Other common formats are 5×7 and 8×10.

Two designs dominate today’s view camera market: the flatbed (in its modern incarnations as field (p. 100), technical (p. 106), and press (p. 105) cameras) and the monorail (p. 99). The 4×5 monorail has become the archetypal view camera and forms the basis for modular camera systems that can be adapted to smaller film as well as modified to become larger-format cameras. Because the individual features of a monorail camera are more obvious than those of any other design, it will be used in this book to exemplify the structure of the generic view camera.

THE MONORAIL VIEW CAMERA

Named for the supporting shaft at its base, the monorail view camera is the most common of today’s large-format cameras. A major characteristic of any view camera is that it provides the physical means to adjust the lens and film positions independently. These adjustments may be made with more freedom and greater ease on a monorail than on a camera of any other design. Inexpensive or studentgrade monorail cameras make lens and film position adjustments and provide for interchangeable lenses, but a professional-quality monorail view camera has additional features that make it much more useful.

The rail clamp attaches to the tripod and provides a solid foundation for the rest of the camera. ■

The versatile, but more expensive, professional monorail cameras are all modular. That is, they comprise a system of interchangeable and interlocking parts and accessories that can be used to assemble a camera tailored to a specific photographic challe...