eBook - ePub

Designing Public Spaces in Hospitals

Nicoletta Setola, Sabrina Borgianni

This is a test

Share book

- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Designing Public Spaces in Hospitals

Nicoletta Setola, Sabrina Borgianni

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Designing Public Spaces in Hospitals illustrates that in addition to their aesthetic function, public spaces in hospitals play a fundamental role concerning people's satisfaction and experience of health care. The book highlights how spatial properties, such as accessibility, visibility, proximity, and intelligibility affect people's behavior and interactions in hospital public spaces. Based on the authors' research, the book includes detailed analysis of three hospitals and criteria that can support the design in circulation areas, arrival and entrance, first point of welcome, reception, and the interface between city and hospital. Illustrated with 150 black and white images.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Designing Public Spaces in Hospitals an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Designing Public Spaces in Hospitals by Nicoletta Setola, Sabrina Borgianni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architektur & Architektur Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The New Spaces of the Hospital

Nature, Physiognomy, Boundaries

What does it mean to talk about public spaces inside a hospital? Talking about public spaces implies speaking about people, flows of people, architectural expression, orientation, accessibility, the identity of an institution and social rights. These very different topics nevertheless find their space–time collocation in these spaces. A person who enters the hospital and asks for information seeking their consultation room; a building that reveals itself on the outside through strong recognition; the social relations created within the lobby; a patient who perceives the space as homey; the possibility of gradually switching from the home to the clinic; and a family member waiting for a loved one: all these phenomena occur within the public spaces of the hospital.

There are no real definitions of what constitutes a public space within the hospital. For experts of contemporary hospital design, these words bring to mind spaces such as the large halls and the corridors nearest to them, spaces that alter the physiognomy of the present-day hospital: the hospital entrance assumes an articulated and complex form, and the structure of the hospital is modelled to incorporate new spaces such as lobbies, real streets, large loggias and covered squares.

In the study of the flows that affect people’s access to the hospital, ‘public’ is the word used to indicate the flow of the user category comprised of visitors, namely people who are not directly involved in receiving treatment but who come to the hospital to visit relatives and friends. In addition to this user category is that of outpatients who come to the hospital for a medical examination or to receive a diagnosis or day treatment.

We can certainly say that public spaces are places where the user first approaches the hospital facility. These spaces are where reception, information and communication, waiting, relaxation and catering activities are carried out. They are therefore reception points for visitors, patients and citizens, and places of transition towards the more healthcare-related functions.

These spaces, in addition to being the point of access to the hospital, are also spaces of public life and relations. In this sense we are supported by Hillier’s theory,1 which identifies buildings as real social objects. The space here plays an active rather than a passive role. It is not only an expression of common values or a setting for individual actions, but also the physical pattern created by the building plays a role with respect to social phenomena, for example useful social interactions.2 This is the configuration through which we can read the “social potential” of a building. In the public spaces of a hospital this potential is strongly expressed with regard to the city and those who must use the facility.

The presence of public spaces in hospitals is also linked to the tendency to increasingly consider the hospital as ‘civic architecture’ and a ‘civic presence’ in the urban and non-urban setting of the built environment, and in the lives of the people.3 Thus it is a building that, through its integration with the urban landscape and urban activities, reawakens the “civic pride”4 of the community it belongs to and in which the community recognizes itself. This physical and functional integration with the city also encompasses a communicative value: for example, the clarity of the access routes in a hospital encourages greater healthcare efficiency, but at the same time it also becomes the symbol of a patient-centred environment.5 Therefore even the idea of the ‘open’ hospital that tends to incorporate new spaces may become a point of reference for the district and town community.6 It accommodates areas dedicated to cultural and social activities that can, for instance, be used by the social services or by voluntary associations. So we realize that the hospital is part of our society; it is a piece of life.

The recent competition launched by Kaiser Permanente in the United States took the topic of the community as a central theme,7 highlighting how integration with the city should not only be considered as a physical extension of some spaces, but also an extension in social and civic terms.8 Promoting the concept of community and creating a relationship with the context in which the hospital is located are two concepts that go hand in hand.

Interface Spaces (between City and Hospital)

The topic of public spaces is strictly connected to the role of the hospital within the city and the hospital in its local dimension of relations with the surrounding populated area. We can refer to the concept of ‘Urbanity’ as expressed by the architect Renzo Piano in a research project for the Italian Ministry of Health,9 namely the importance of integration in the urban fabric with different levels of the surrounding environment.

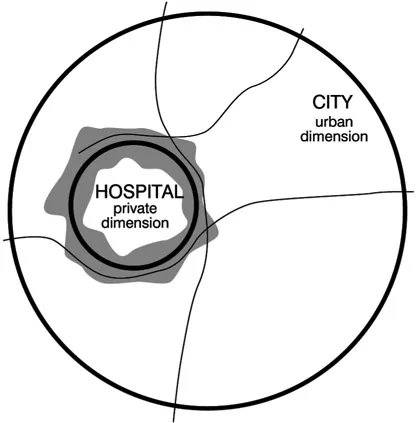

To obtain this integration, the public spaces acquire a fundamental role. The presence of these spaces reintegrates the hospital building within the city: indoor and outdoor squares, loggias, entrance doors and roofing are elements that act as a hinge between the city space and the hospital space. We can define public spaces as interface spaces, namely a connection between two dimensions: the urban one of city life and the gradually more private one of hospital life (Fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Public spaces as interface spaces between the city and the hospital

The interface spaces do not have such a clear and defined boundary: even a road that skirts the perimeter of a hospital area can be an interface space. Along this road are public transport hubs for reaching the hospital, commercial businesses (newsstands, restaurants, bars, florists) that can be used by people visiting the hospital – whether they be staff or other users – and car parks for hospital users. This road is travelled by people entering and leaving the hospital and by those who use it to reach other places within the city.

The interface spaces play a strategic role in hospitals.10 They are spaces that transform over time and have the potential to shape the contemporary hospital11 as well as the city. Hospitals often occupy entire blocks of the urban fabric, and the interface spaces thus become an opportunity to redesign portions of the city and redevelop other areas. The hospital thereby acquires its own urban quality,12 assuming an urban value that becomes the driver of redevelopment in our cities.

There are two spheres in which integration of the hospital with the city can chiefly occur: functional and spatial. The first concerns the organizational strategies of those who manage the hospital, which take the approach of opening up some areas of the hospital to public use and supporting the healthcare functions with other commercial and recreational functions in general: for example, introducing various types of restaurants and shops, and providing recreational spaces for citizens’ associations such as rooms for activities and auditoriums or therapy spaces such as rehabilitation gyms. These actions help to bring urban vitality inside the hospital and social integration to the city.13

The second sphere, namely the spatial one, concerns the physical integration of places and routes within an urban network comprised of spaces outside the hospital, interface spaces and indoor spaces (corridors, stairs, lifts, halls). The physical continuity of these different public spaces provides greater accessibility to the healthcare environments and more active utilization of the spaces for public use within the hospital. Constructing this integration through the interface spaces is the task of design in the contemporary city.

Figure 1.2 Portico of the Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence and detail of the roundels by Della Robbia

The modern Western city from the eighteenth century was constructed around the spatial separation of functions, codified at the start of the twentieth century in zoning, while the contemporary city, like the rest of the ancient city, albeit due to different factors, presents unstable differentiations and fragmentations. In the modern city the main urban facilities, including the hospital, become areas of specialization, “islands separate from the urban context”.14 It was not like this in the ancient city: the Ospedale degli Innocenti, the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence, and the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena, were urban places of meeting and integration.15 The Ospedale degli Innocenti16 (Fig. 1.2) is a hospital perfectly assimilated into the urban context; its loggia faces onto Piazza Santissima Annunziata and has roundels with reliefs of babies in swaddling clothes produced by the sculptor Della Robbia, acting as a reminder of the hospital’s job of taking in abandoned infants. The façade thus structured helps to create the square and at the same time confers symbolic meaning communicating the social and functional value of the hospital complex. The second, and perhaps even more effective, example is the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova. It stands in the centre of the city in a homonymous square and has been a working hospital since the year of its foundation (1288). Here a Renaissance loggia embraces the square; over time it was extended to form three sides and a system of cloisters and courtyards that receive people from the entrance taking them through to the interior of the block. In Siena the hospital complex of Santa Maria della Scala (Fig. 1.3), a hospital totally immersed in the city’s civic centre now used for public functions, was built on the square right opposite the cathedral, occupying a large block, and was the source of inspiration for the construction of other European hospitals.17

Figure 1.3 The entrance to Santa Maria della Scala Hospital in the cathedral square in Siena

A contemporary example of the urban integration of the hospital can be found in the Future Hospital international design competition organized by the Netherlands Board for Healthcare Institutions (NBHI) in 2004, which envisaged an innovative hospital concept: compact general hospital, shops, theatre and parking garage. The winner of the competition was the Core Hospital design by Ton Venhoeven,18 designed so that it could be constructed within the city “where it profits from its environment, where it is easily accessible for pedestrians and where it contributes to the health and quality of urban life”, therefore a hospital in which the patient can find markets, shops, restaurants and the vibrant life of the city in the immediate vicinity and that provides for an internal connection with “comfortable accommodations for family members, doctors, tourists and business travellers”.19

Figure 1.4 The covered square of Hospital del Mar in Barcelona

But others too are exemplary contemporary hospitals for the urban integration project. The Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou in Paris (France) is crossed by an urban road and faces onto an urban park; the Hospital del Mar in Barcelona (Spain) (Fig. 1.4) was extensively redeveloped and can be accessed from a new covered square (the Palio) that connects with the city and the La Barceloneta park;20 the New Karolinska Solna in Stockholm (Sweden), which with its pavilions recreates a real urban district with a square for the city; and the Bellevue Hospital in New York City (NY), which was recently expanded with an outpatient clinic area hinged to the old facility with a full-height light-filled atrium that looks just like an urban space.

When the hospital stands in an isolated area outside of the city or in a low-density urban area we witness the formation of a different type of urbanity. The urbanity in this case is all ‘inside’ the hospital in an attempt to recreate the typical environments of the city: streets and squares with different functions that overlook them, the presence of elements of street furniture and green areas, courtyards, underpasses and gates.21 This is the case of the Walter Mackenzie Hospital in Alberta, Canada (1984) and the Atrium Medical Center in Heerlen, the Netherlands (2003). Therefore the integration at times really refers to urban models of the past, not only from a formal but also a material point of view. This is the case of the Riks Hospital in Oslo, Norway (2001), which was designed takin...