eBook - ePub

The Legacy of Mesoamerica

History and Culture of a Native American Civilization

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Legacy of Mesoamerica

History and Culture of a Native American Civilization

About this book

The Legacy of Mesoamerica: History and Culture of a Native American Civilization summarizes and integrates information on the origins, historical development, and current situations of the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. It describes their contributions from the development of Mesoamerican Civilization through 20th century and their influence in the world community. For courses on Mesoamerica (Middle America) taught in departments of anthropology, history, and Latin American Studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Legacy of Mesoamerica by Robert M. Carmack, Janine L. Gasco, Gary H. Gossen, Robert M. Carmack,Janine L. Gasco,Gary H. Gossen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Anthropologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

SozialwissenschaftenSubtopic

AnthropologieUnit 2: Colonial Mesoamerica

Chapter 4

Mesoamerica and Spain:

The Conquest

For three centuries, the Mesoamericans were part of a vast colonial empire ruled by Spain. Spanish domination profoundly altered the culture and history of Mesoamerica’s indigenous peoples. Old World infectious diseases, combined with violence and exploitation, killed millions of people; new technologies and new plants and animals had a deep impact on local economic and ecological adaptations; and new social and religious customs were imposed. Spanish rule also introduced new categories of people into the social scene: Spaniards and other Europeans; the Africans they brought as slaves; and people whose heritage mixed Indian, European, and African ancestry in every possible combination. The native people who survived these upheavals found themselves at the bottom end of a new social hierarchy, with power concentrated in the hands of the foreigners and their descendants.

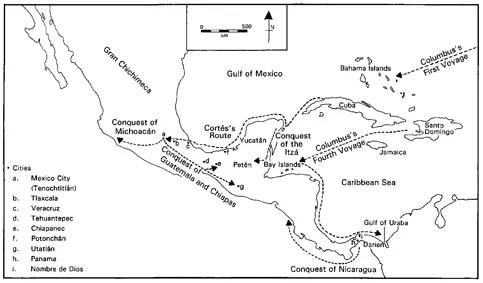

In this chapter we present a historical overview of the Spanish invasion, in order to explain how this small European nation came to rule over the densely populated, socially complex, and highly militarized Mesoamerican world described in the preceding chapters (Figure 4.1). Particular attention is given to the beliefs and motivations of the actors on both sides of the conflict. We begin by examining events in Spain’s history that led up to the country’s colonial enterprise and affected its course in many ways.

THE ORIGINS OF SPANISH IMPERIALISM

Spanish imperialism grew out of the Christian “reconquest,” or reconquista, of Spain from the Moors. The Moors were Muslims of North African descent, whose Arab and Berber ancestors had conquered most of the Iberian Peninsula between A.D. 711 and 718. The Moorish rulers in Spain presided over a cosmopolitan, multiethnic society in which Jews and Christians were tolerated and permitted to practice their religions. Many Spanish Christians, however, found rule by these foreign “infidels” unacceptable, and bands of independent Christians challenged Moorish rule from their bases in mountainous northern Spain.

Figure 4.1 Map showing the main routes by which the Spaniards conquered the Mesoamerican world.

During the ninth century, the originally united Muslim state fractured into many small and competing kingdoms. Thereafter, Christian armies from the north were able to confront their Muslim enemy one faction at a time. Between A.D. 850 and 1250 the balance of power gradually shifted until the only remaining Moorish kingdom was Granada, a wealthy mountain stronghold in the south of Spain. The rest of the peninsula was dominated by the Christian kingdoms of Portugal in the west, Castile in the north and center, and Aragon in the northeast.

For the Christians, the conflict with the Moors was a holy war: The Islamic religion was seen as evil and the Muslim way of life as sinful. Spanish soldiers believed that Saint James, the patron saint of Spain, not only sanctioned their quest but also often appeared before them on a white horse, leading them into battle. Religious faith and military zeal went hand in hand; these in turn were barely distinguishable from political and economic ambitions. That Christ’s soldiers should enjoy the material spoils of victory, appropriating the wealth and property of vanquished Moors, was seen as no more than their due reward.

Over the centuries of the reconquista, Spanish Christian society came to glorify military achievement. Lacking ancestral ties to particular pieces of territory, the aristocracy was highly mobile, counting its wealth in herds of domestic animals rather than in agricultural land. The knights who conquered a territory would move in as its new overlords, being rewarded for their military service with rights to tribute and labor from the subject population. Soldiers recruited from the peasant class would be given parcels of land in the new territory, which they owned outright (in contrast to the serfdom prevailing elsewhere in Europe). The Christian kings found their power always circumscribed by the need to placate the nobles, on whose military prowess they depended for the conquest of additional lands; as a result, there was constant tension between the central authority of the monarch and the local concerns of the feudal lords.

After a long hiatus marked by the Black Death and by factional disputes within the Christian kingdoms, the reconquest resumed in 1455 under King Henry VI of Castile. In 1469, Henry’s eighteen-year-old half-sister and heir, Isabella, married seventeen-year-old Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the much weaker kingdom of Aragon. After much political intrigue, including a civil war in Castile, the couple emerged as the powerful rulers of a united Spain. They succeeded in limiting the influence of both their own nobles and the pope. Themselves very pious, they used religion as an effective means of promoting national unity. They established the Spanish Inquisition as a tool for enforcing religious conformity among Spanish Christians, including increasing numbers of conversos, or converts from Judaism, and moriscos, or Christianized Moors, thousands of whom would be executed as heretics. The couple’s close ally Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, a Franciscan priest and Isabella’s confessor, raised the standards of orthodoxy and austerity among the religious orders, especially the Franciscans, and sought to revitalize the religious faith of the entire populace. Appointed Archbishop of Toledo in 1495 and Inquisitor General in 1507, Cisneros was the most powerful individual in Spain apart from the king and queen themselves. He twice served briefly as regent of Castile, following Isabella’s death in 1504 and Ferdinand’s in 1516.

Isabella and Ferdinand sponsored scholarship in the humanities, earning an international reputation as patrons of learning. Among their circle of learned associates was Antonio de Nebrija, a converso scholar who in 1492 published the first grammar of a modern, spoken language, as opposed to Latin and Greek. Nebrija’s Grammar of the Castilian Language elevated Castile’s dialect of Spanish to a privileged position previously restricted to those ancient languages. It thus helped to legitimize Castile’s supremacy over the rest of Spain, and beyond: When first presented with the book, Isabella reportedly asked its purpose; the Bishop of Ávila, speaking on Nebrija’s behalf, explained, “language is the perfect instrument of empire.”

His words were apt, for the year 1492 launched Spain on its way toward becoming the world’s most powerful state. Early that year, Isabella and Ferdinand had seen the reconquista come to an end: The forces of Christian Spain marched victorious into Granada on January 2. With the Moorish frontier closed at last, Spain’s heavily militaristic and aristocratic society might have settled down to focus on internal economic development. The towns were already dominated by a middle class of tradespeople and entrepreneurs; production of certain goods, especially wool and leather, was in the process of industrialization. However, other events of 1492 steered the nation onto a different track.

On March 30, 1492, Isabella and Ferdinand signed a decree demanding that all Jews be expelled from Spain within four months. A campaign to force Muslims to convert began in 1499, with an edict of expulsion following in 1502. Prior to the fall of Granada, Jews actually had fared better in Spain than elsewhere in Europe. Spanish Christians knew that any Jews or Muslims expelled from Christian-held territory would have been welcomed in Moorish lands, where their skills and assets would only strengthen the power of the Moorish rulers. But after the conquest of Granada, there was no longer any such refuge, and in the climate of religious fervor that accompanied the culmination of the reconquista, Spain’s rulers opted to impose their faith on all their subjects.

Between 120,000 and 150,000 Spanish Jews left the country; today’s Sephardic Jews are descended from these exiles. Thousands more, like the majority of the Moors, chose to convert to Christianity, at least in name, rather than leave their homes and property. As conversos, the descendants of Jewish families often continued to practice at least some Jewish customs in secret, and they were always at risk of being tried by the Inquisition for real or alleged Judaic practices. Some were attracted to Christian religious orders, such as that of the Franciscans, that were somewhat compatible with their own traditions of scholarship, prophecy, and mysticism. Scholars from converso families contributed significantly to the sixteenth-century flowering of Spain’s universities.

The departure of the majority of Spain’s Jews took a tremendous toll on Spain’s economy. Jewish merchants and financiers had dominated the middle class; without their skills and trading networks, Spain’s commerce was devastated. Jewish traders were replaced not by upwardly mobile Spanish Christians but by foreigners who took their profits out of the country. What had been a thriving and industrializing commercial system sank into centuries-long stagnation.

On August 3, 1492, a Genoese mariner named Christopher Columbus set sail from Spain on a voyage sponsored by Isabella and Ferdinand. The goal of the enterprise was to discover a westward route to Asia and to claim Spanish sovereignty over any previously unknown lands found along the way. For the Spanish rulers, such a route—and their control over it—would facilitate trade for such items as silk and spices as well as giving them access to whatever riches might lie in undiscovered lands.

Their interests were more than economic, however, for Columbus and his Spanish patrons envisioned a worldwide religious crusade. They hoped that with a Spanish-controlled route to Asia, the struggle against Islam could be continued beyond Spain’s borders. The abandoned medieval crusade to establish Christian control over the Holy Lands, which were then part of the Ottoman Empire of the Turks, could be restarted under Spanish leadership, financed by new wealth from the western trade. In effect, a westward passage would allow Christian armies to sneak up on the Turks (and other Islamic peoples) from behind, rather than having to battle their way eastward through the Turks’ formidable defenses. Furthermore, the non-Islamic peoples of Asia might be converted to Christianity. Not only would such conversions be pleasing to God, but also the new converts, potentially numbering in the millions, would swell the ranks of the Christian armies as they passed westward toward what might be the ultimate battle between the followers of Christ and the followers of Mohammed.

But on October 12, Columbus and his men stumbled upon an island in the Caribbean. That island proved to be one of many lying adjacent to two large continents. Instead of establishing new links to Asia, Isabella and Ferdinand found themselves presiding over a massive project of exploration, invasion, and conquest, as the lands Columbus mistook for the “Indies” were forcibly transformed into colonies of Spain.

SPAIN’S COLONIAL ENTERPRISE BEGINS

The leaders of Spain believed that they had a God-given right to dominate non-Christian peoples and to bring to them the word of Christ; the fact that the “new” lands were revealed to Columbus while he sailed under the Spanish flag was proof enough of divine intent. Spanish claims were further legitimized by Pope Alexander VI, himself a Spaniard, who issued a papal bull in 1493 giving Spain the right to explore westward and southward and to claim any territory not already under Christian rulership.

This act ran afoul of Portugal, which was engaged in expeditions in the eastern Atlantic and along the coasts of Africa. In 1493, Spain and Portugal agreed to divide between themselves the right to explore and conquer unknown parts of the world. This Treaty of Tordesillas declared a line of demarcation, which passed through the Atlantic Ocean 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands (which Portugal already claimed). Spain had rights to everything to the west of this line and Portugal had rights over all lands to the east. Spain, though intending to claim all of America, had inadvertently yielded to Portugal the eastward-projecting mass of Brazil.

Once Spain’s rights to American territory had thus been formally recognized, the process of invading and conquering these lands could be treated juridically as a process of pacification. Native peoples who declined to recognize Spanish dominion were by definition rebelling against their lawful rulers and thus inviting violent retaliation and suppression. Native groups that submitted peacefully to Spanish rule were merely performing their duty as Spanish subjects. This “myth of pacification” served to justify the Spanish invasion and mask its accompanying brutality behind a facade of legitimate statecraft.

The reconquista had won back previously Christian territories from the descendants of Muslim invaders. The conquest of America was an aggressive campaign against peoples who had never heard of, let alone threatened, Spain. However, for many Spaniards the invasion of America was a logical continuation of their struggle against the Moors, led, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- List of Figures

- List of Boxes

- Introduction

- Unit I Prehispanic Mesoamerica

- Unit II Colonial Mesoamerica

- Unit III Modern Mesoamerica

- Unit IV Mesoamerican Cultural Features

- Glossary

- Bibliographic References

- Index