![]()

Part 1

Understanding Public Interest Design: Essays

![]()

1

The State of Public Interest Design

Bryan Bell

The field of public interest design is quickly emerging. And while there has been growing momentum over the last fifteen years, much remains to be done. What we are now beginning to see is a realization of the full potential of design—the highest and best use of design to serve 100 percent of the population. We are seeing the emergence of what can rightly be called public interest design (Bell 2013, 52). While this relationship between design and the public interest has come more into focus during the last decade, we are still at the beginning of what needs to happen. We need to move past catchy names and rallying cries into a deeper understanding of how this potential can be fulfilled.

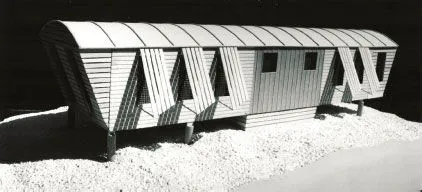

Evidence has been growing over the past fifteen years of the many designers engaging in projects of public benefit around the world. My own work in this sector began in 1990 when I left Steven Holl’s office to design housing for migrant farmworkers, although I did not know what to call the work then—I was simply the “non-architect” or the “alternative career” person.

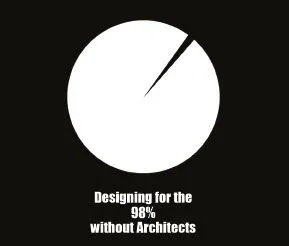

My research into this field of work started in 2000 when the nonprofit organization I founded, Design Corps, held the first “Structures for Inclusion” conference at Princeton University during which we made the challenge to “Design for the 98% without Architects.”

Designing for the 98 percent has served since then as a rallying cry for this growing movement that is now becoming a profession.1 This slogan, that so well illustrates that designers have only been serving the very few, symbolizes how much work we still need to do before we can use design to address the most critical challenges we face in the world.

1.1

Migrant Farmworker Housing Unit: In 1989, when Bell moved to rural Pennsylvania to design and build housing for migrant farmworkers, he did not know what to call his field of work. He now understands it is public interest design. Design: Bryan Bell, Model: Mathew Heckendorn.

The research and documentation of this work has focused on individual projects and individual people. But individual projects and individual people have a major problem—they can all go away. They lack the advantages of collective action. To reach its potential, this movement must become permanent and effect systemic change. This work must resonate at a deep cultural level. We must understand and make clear how these individual projects and people add up to a collective action that provides a value so deep the public will make sure that it does not go away. The challenge is to find a cultural basis for design that will provide value to 100 percent of the general public (Bell 2013, 52).

So to build a field of public interest design that can grow to serve 100 percent of the public, we need to make clear the public benefits of design. These are beyond the scope of the design professions as they are currently defined, which is largely based on the needs of individuals or private institutions that can afford to pay the professional fees for services. Similarly, the standards of practice that deliver these benefits are yet to be fully clarified. This clarity is essential to create the understanding and trust of service the public deserves.

1.2

In 2000 Design Corps held the first “Structures for Inclusion” conference at Princeton University called “Design for the 98% without Architects”, which is now a rallying cry for public interest design.

What does it mean to be a profession? It means to profess a mission. With a mission, public interest design is an emerging field, like public interest health that arose from the medical profession. Without a mission, design can be seen merely as an advanced technical skill. While technical skill is certainly valuable to society, it does not serve the greater public good. “This is because more fundamental than the other defining features of a profession (a specialized body of skills and knowledge, a code of ethics, a community that controls who can practice, etc.) is its raison d’être: ‘to serve responsibly, selflessly, and wisely’” (Gardner and Shulman 2005, 14).

Other professions that serve the public have resonating values deep in our culture. The United States Constitution states the ideal of equal justice that is the cornerstone of the legal profession. The Hippocratic Oath, which originates from fifth century bc, offers an ethical foundation for health care professionals. What is the collective mission of public interest design?

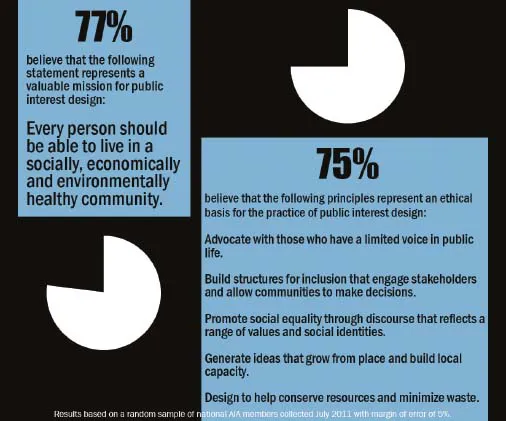

To understand what the mission of public interest design should be, I surveyed a representative sample of the national AIA membership as part of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) College of Fellows Latrobe Prize.2, 3 I asked those surveyed whether a specific statement would be an appropriate mission if a profession of public interest design were to exist. Seventy-seven percent agreed with the following mission: “Every person should be able to live in a socially, economically, and environmentally healthy community.” (This mission was originally determined through a democratic decision process in 2005, conducted among the two hundred founding members of the SEED Network.)

In the Latrobe survey I also sought to understand what principles could define the expected field of practice aligned with this mission. The question was posed: “If a profession of public interest design was to exist, would the following be an appropriate mission?” Seventy-five percent agreed with the following principles:

• | Principle 1: | Advocate with those who have a limited voice in public life. |

• | Principle 2: | Build structures for inclusion that engage stakeholders and allow communities to make decisions. |

• | Principle 3: | Promote social equality through discourse that reflects a range of values and social identities. |

• | Principle 4: | Generate ideas that grow from place and build local capacity. |

• | Principle 5: | Design to help conserve resources and minimize waste. |

1.3

A survey of the members of the American Institute of Architects showed a strong consensus for the SEED Mission and Principles as being a mission and principles for the practice of public interest design. Source: Survey conducted by Bryan Bell and the American Institute of Architects (AIA) for “Wisdom from the Field: Public Interest Architecture in Practice,” by Roberta Feldman, Sergio Palleroni, David Perkes and Bryan Bell, 2013; Funded by the AIA College of Fellows 2011 Latrobe Prize.

These survey questions started to provide the needed clarity to define the foundation for the profession of public interest design. The principles set the stage for a vision of success and a way to measure success within the field. A review of these principles confirms the core relationship between design and democracy—the use of the democratic decision making process is clear in Principles 1, 2, 3, and 4.

The recognition of a clear and accepted mission and principles is an important step to defining a profession. The survey responses show the beginning of that collective understanding that public interest design is the practice of design, with the goal that every person should be able to live in a socially, economically, and environmentally healthy community. The research also showed that those practicing public interest design take a holistic approach, considering a broad range of social challenges not dissimilar to the field of public health that we draw much inspiration from. Public, interest design also seeks to provide services to the entire general public, as does public interest law. The ideals of democracy echo in the cultural foundation and values of public interest design. Design and democracy are linked in a deeply powerful way that is both idealistic and practical—and both can be strengthened by building the relationship within them.

The value of this relationship was given evidence through the Latrobe research done by Roberta Feldman, Sergio Palleroni, and David Perkes. They interviewed 118 public interest design practitioners. Ninety-three, or 78 percent, cited the value of stakeholder participation in the design process. This high percentage of interest in collective decision making supports a democratic design process in the practice of public interest design.

From these findings, we move to a “value proposition,” a statement about what the democratic design process provides that is of value to the public. Public interest design efficiently allocates public resources to address a community’s highest priorities through a democratic decision making process that is transparent and accountable (Bell 2013, 52).

Identifying a mission, principles, and value proposition starts the process of clarifying what public interest design can hope to contribute for the public good. Not only should a building provide shelter and meet basic functions but also, through design, it can meet the higher goal of providing a socially, economically, and environmentally healthy community while supporting a democratic and inclusive decision making process (Bell 2013, 52).

Growth with Caution

Every new field that has emerged to serve the public goes through an initial phase of defining itself. In addition to a mission, principles, and a value proposition, professional standards need to be defined. Professional standards determine the level of performance that people are expected to achieve in their work as well as the knowledge and skills they need to perform effectively in their field. Professional standards form the principles of conduct governing an individual as a part of a professional group. The reason for these to be clear is to assure the public what they can expect while holding practitioners accountable to established criteria.

When professions fail to make these clear, the value of a profession can be compromised and the public trust jeopardized. During the 1930s, pioneers like photographer Dorothea Lang created a public demand for social justice with her camera. However, this field had no clear professional standards, and writer Erskine Caldwell violated what is now an established code of conduct. Having a personal ethic that did not distinguish between fiction and non-fiction, Caldwell fabricated quotes for photographs of poor rural Southerners that were taken by his partner, Margret Bourke-White (Broadwell and Hoag 1982).4 His fictitious captions were juxtaposed with photographs of real people without their consent, an act unimaginable today under current professional standards of journalism. Taking these photos would also be considered unethical by the standards that have come to define a profession with great public value.

A similar violation to professional trust happened during the early days of public interest health when standards of practice had not yet been established. In 1932 the U.S. Public Health Service conducted the Tuskegee syphilis experiment to study the effects of syphilis among poor rural African Americans in Tuskegee, Alabama. The six hundred men studied were not told what disease they had contracted and were intentionally untreated with penicillin when it was established as a cure in 1947. The experiment continued until 1972. The victims of the study included numerous men who died of syphilis, wives who contracted the disease, and children born with congenital syphilis. As a result of such misguided experiments, public health now has self-imposed standards of informed consent in any situation where human subjects are involved.

One key question raised by these two incidents is how these professionals could take actions that clearly violate what we now understand as the ethical foundation for journalism and public health. The answer is that they were acting under their own personal standards, not a set of professional standards. Professional expectations had not been determined yet, and there was no professional accountability.

1.4

A doctor and patient of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study conducted by the U.S. Public Health Services between 1932 and 1972 to study untreated syphilis in rural African American men. The patients thought they were receiving free health care from the U.S. government and did not receive a cure when it became available. The study was conducted without the patients’ informed consent. The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

How do we create accountability in public interest design? To do so, we must first determine if public interest design is a general term that anybody can use to describe any intention and any agenda or a specific standard that can be measured and verified. This moment in the development of public interest design strikingly parallels the moment a decade ago when many things were called Green Design. Because there were no standards for what constituted a “green” practice then, this term could easily be abused. Without accountability, public interest design could face a similar predicament in which design claims to be in the public’s interest, but there are no standards to measure or uphold the validity of these claims.

I believe that the term public interest design means that the design is in the interest of the public; and if it is not, it should not misrepresent itself. Data from the AIA Latrobe Prize survey of the architecture profession address whether this should be a regulated profession that self-maintains standards. In the survey, 57 percent of architects said that an ethical violation should result in removal, which confirms that, at least as far as licensed architects are concerned, there is support for a professional field with accepted practices that should not be violated. Public interest design is not just a term to be freely used by anyone to describe anything remotely related. It is a profession, and the practitioners need to be held accountable.

Now Is the Time

We are now at the critical moment in time when public interest design is taking shape into this specific field of practice, a moment when the disparate activities of individual projects by individual people from across design disciplines are no longer just separate efforts. While design professions are ancient in many ways, from planning cities and designing buildings to shaping tools and creating lucid communications, ideas about the public benefit of design are just now being made meaningful.

If public interest design is to move from its current limited role to realize its greater public value, we must face our challenges. As a first step, public interest designers need to change our self-vision and the goals we set for ourselves in our work. We need to change the public perception of what and how we can contribute to the greater common good. This is already happening. The collective consciousness of design is changing. This shift gives us an opportunity to do more good work and to make a permanent change in our collective futures. The massive shift we need is not going to happen by supernatural forces. It will only happen when many of us become engaged—by the design community becoming activists for the human community.

The need for public interest is undeniable. We can design for 100 percent of the public. This is when we realize our full potential. We need to learn from the best practices presented in this publication. We need to show the public what value this field has for them by addressing their most critical issues. But while progress has been made, much more progress is needed. Public interest design i...