eBook - ePub

Unbuttoned

The Art and Artists of Theatrical Costume Design

Shura Pollatsek

This is a test

Share book

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Unbuttoned

The Art and Artists of Theatrical Costume Design

Shura Pollatsek

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Unbuttoned: The Art and Artists of Theatrical Costume Design documents the creative journey of costume creation from concept to performance. Each chapter provides an overview of the process, including designing and shopping; draping, cutting, dyeing, and painting; and beading, sewing, and creating embellishments and accessories. This book features interviews with practitioners from Broadway and regional theatres to opera and ballet companies, offering valuable insights into the costume design profession. Exceptional behind-the-scenes photography illustrates top costume designers and craftspeople at work, along with gorgeous costumes in progress.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Unbuttoned an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Unbuttoned by Shura Pollatsek in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

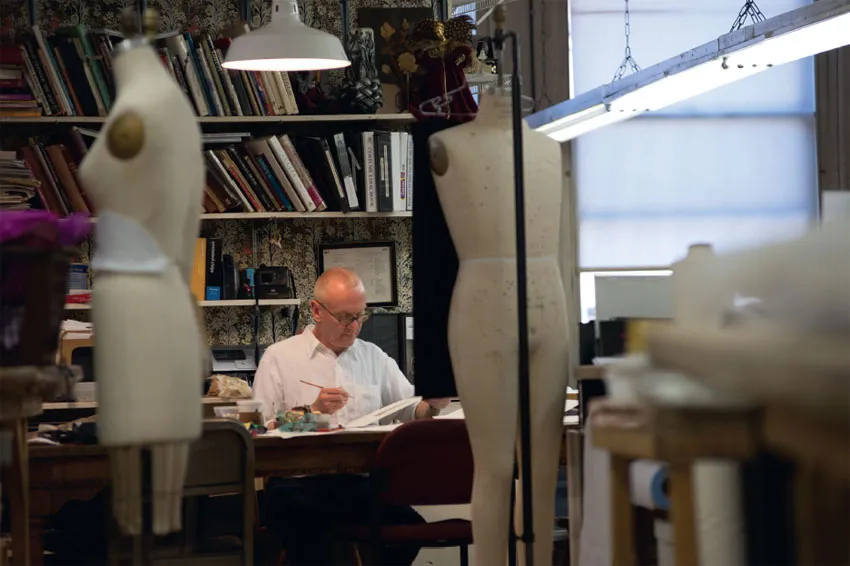

Designer Alain Germain pages through a book of his designs.

1

Design

CREATING THE VISION

For the costume makers, whose work we explore in this book, the process starts with the costume design sketch. For the costume designer, the journey begins with a script and a vision. Unlike a fashion designer, for whom the clothing is the end product, a costume designer’s product is actually the character. The clothing helps to illuminate the social role and personality of each member of the story. The visual tableau created by the combination of characters onstage gives insight into the plot and themes of the performance. The context of every costume is extremely important. Designers create each look for a specific performer playing a specific role at a specific moment in a story. A full skirt might be designed so that the stiff fabric will sway and snap when the actress does her choreography, or the actor’s clownish interpretation of his role might inspire a too-tight suit jacket and bright tie. When costumes are successful, the designer’s role is imperceptible. Instead, the clothing becomes a natural part of the character onstage.

Germain with an original painting at his studio in Paris.

Design for the stage is a collaborative art, led by the director. Costume designers work as part of a creative team of artists. This production team, comprised of scenic, lighting, sound, and costume designers, meets with the director and/or choreographer to discuss the story and to find a vision for the particular production. The director shares his or her initial thoughts, and then after a group discussion, the designers begin their own explorations, looking for a way to translate the ideas to the stage. Most start with research into the era and style of the piece, many readings of the script, and listening to music if there is any. Over a series of meetings, they discard many sketches and rework countless ideas. Finally the costume designs evolve into finished color paintings, called renderings. However, the designer’s work is not done yet. As the actors rehearse with the director, their interpretations of their roles may inspire adjustments, large or small, to the designs. And as costumes enter the construction phase, the collaboration also continues. The best costume technicians do not merely execute the design; they add their own artistry as they interpret it, much as musicians playing from printed sheet music produce their unique version of a song.

The designer has a series of meetings with those who will source the materials, make the patterns, dye the fabrics, and sculpt the accessories. As the costume technologists look at the renderings, they ask the designer logistical questions. What kind of fabric is the dress made from? How does the coat open? Does the performer remove the mask onstage? The production team is now armed to start work, but they continue to check in periodically with the designer as they build. Rough draft, or “mock-up” versions are made first, and most garments are fitted on the performer in multiple sessions, giving both designer and artisan a chance to make aesthetic and practical adjustments.

Fittings are a critical phase of a designer’s work. The costume a designer sees in her mind as she draws is not a fully realized idea. No matter how experienced the designer, nor how detailed the sketch, the three-dimensional garment on the moving, breathing performer brings up new questions and demands adjustments. Maybe the hemline looks better on the actress above the knee than below, now that the fight scene the director added necessitated a change from heels to flats. Maybe the pant leg needs to be a bit narrower than was fashionable in the 1930s to keep the actor from seeming frumpy to the modern eye. Maybe the wings protrude at the wrong angle from the dancer’s back once she has done a few pirouettes. The fitting is also a chance to see the whole costume together: the clothing, the hat, the shoes, and even the wig. While additional fine-tuning will occur during dress rehearsals, everyone prefers to first work out as many kinks as possible in the relative calm of the costume shop.

Just because a show has opened on Broadway does not mean the designer’s job is done. When a Broadway show goes on tour, the overall look of the show remains the same, but the set, costume, and lighting designers adjust their original visions to be portable, and of a slightly more modest scale. Martin Pakledinaz was tasked with reworking his original costume designs for Thoroughly Modern Millie into an efficient touring package. He cut a few of the outfits for the leading ladies. Plenty of glamor remained, though—the title character still wore seven dresses every evening. His greatest change was to give the members of the chorus a more modular look. Instead of a complete new outfit for each of the big numbers, they changed jackets, hats, and accessories to shift from people on the street to speakeasy revelers to high society party guests. To ensure that the color combinations in this new version would still create a dynamic yet balanced stage picture, Pakledinaz’s assistants made a poster-sized chart. Along the side was a list of all the characters and along the top were the dozens of scenes in the show. Each box in the grid represented a character in a given scene. The assistants filled each box with small pieces of the fabrics that made up the costume, such as a larger patch of the suit fabric, a small square of shirt color, and a sliver of tie. Using the chart, the designer could see the entire show at once without covering the office in a blanket of costume sketches. The designer and director could easily discuss the sequence of outfits for one character, or see the grouping of printed silks in a dance number. Pakledinaz checked that there was never a moment where too much of one color was used, or a scene where Millie did not stand out as she should. Despite having won the Tony Award for his Broadway design, Pakledinaz decided afterwards that he preferred the streamlined look of the tour.

THE BOLD COLORIST—RICHARD HUDSON

Richard Hudson is a costume and scenic designer with a distinguished career in theater, opera, and ballet design. He is probably best known for his scenic design for The Lion King, which won numerous awards including the Tony. Hudson grew up in what is now Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia) “in the middle of the bush.” His interest in performance was sparked as he and his siblings created their own entertainment. “One of my greatest passions when I was tiny was puppets, and doing puppet shows,” he recalls. “I think that is what first engendered my enthusiasm for the theater.” Later Hudson made his actual theater debut at boarding school, where the students presented plays. He made his contribution offstage, by painting the scenery. At the age of eighteen he left Africa for London, where he attended the Wimbledon School of Art. “Certainly one of the things I love most about my job is the collaboration. That’s really what it’s all about, right from the beginning of the project, when working with a director or a choreographer discussing what they feel about the piece…. Of course it’s not just a question of collaborating with the drapers and the people who are making the costumes, but quite often talking to the people who are going to wear them. I do quite a lot of opera, and often work with big opera stars. It’s obviously part of my job to talk to them about what they are going to wear.”

The American Ballet Theatre in New York City is presenting a new production of The Nutcracker at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, with scenery and costumes by Richard Hudson. For this production of the beloved Christmas ballet, choreographer Alexei Ratmansky requested a traditional style, but Hudson’s designs will have a distinctly different look than the classic New York City Ballet production, costumes designed by Barbara Karinska in 1954. Hudson chose to set the first act in the early nineteenth century, with a Northern European feel. Before he puts pen to paper, Hudson fills a file with research. Costume designers typically gather images from the time such as fashion illustrations, paintings, and photographs of vintage garments. For the second act, when the ballet takes us to the “Land of Sweets,” he switches gears. Hudson, known for his distinctive and bold use of color, has carefully plotted out tableaux of “very brightly colored” costumes against more abstracted settings. “The Arabian girls are dark red and gold, the flowers in ‘The Waltz of the Flowers’ are quite bright pink. The set for the second act is a turquoise surround with a lime yellow. And then it changes right at the end of the second act, for the pas de deux to, sort of a deep purply blue.”

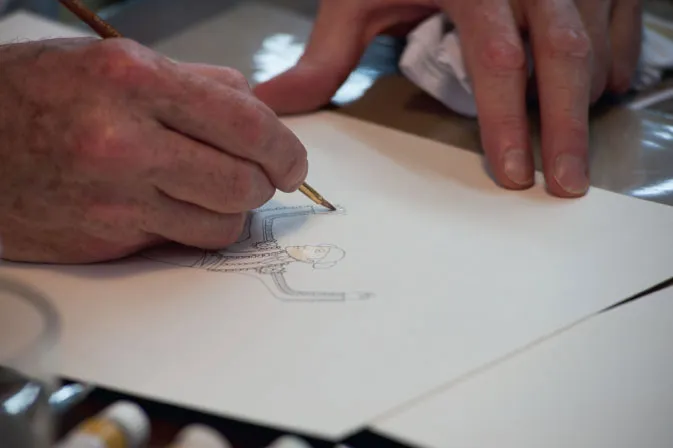

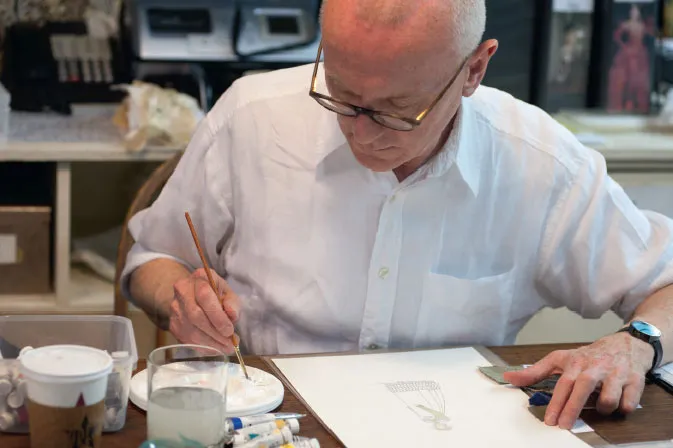

Designer Richard Hudson painting at Barbara Matera Ltd. costume shop.

Hudson puts finishing touches on his designs for American Ballet Theatre’s production of The Nutcracker.

Hudson and Tim Blacker at Barbara Matera costume shop in New York.

Once Hudson is satisfied with his research, he tries out ideas in a sketchbook, and then finally draws and paints his finished renderings. The paintings show the overall look of the costume, but as he meets with the costume shop, they will also refer to research and detail sketches, for the paintings cannot contain all of the information. Experienced pattern makers will already be familiar with the historical shapes, but the designer’s research helps to show them which nuances and variations of the period he prefers. To convey the exact shapes of the embroidery for Clara’s bodice, he included both a detail drawing and a photo of the scrollwork on an antique mirror that inspired him. Despite having such a specific vision of his work, Hudson “loves it when people make suggestions. I am not autocratic. I love the collaborative process and the fact that everybody chips in. I think the best projects are ones where you can’t remember who thought of what. It all comes together.”

The London-based Hudson is spending time in New York to coordinate with the shops hard at work translating his designs into clothing and scenery. His clear sketches and binder of research give the costumers at Barbara Matera Ltd. an excellent starting point, but the translation to three dimensions still requires input from the designer. Hudson will meet with the shoppers to select fabrics and trimmings for each element of each costume, discuss silhouette and proportion with the pattern makers, and finesse fit and shape on the individual performers. The lines and swirls in his sketches will be translated into embellishments like beading, embroidery, and painting, and he will work closely with the artisans as they sample techniques and colors. However, the costumes won’t be truly finalized until dress rehearsal, when Hudson will witness his creations in their full context: onstage, in motion, under colored stage lights. Then he, together with choreographer Ratmansky, will critique the look of the show. The designer will have his final chance to edit, and will ensure that hem lengths are adjusted, paint colors are brightened, and earrings with more sparkle are added before audiences see the ballet.

A PASSION FOR COLLABORATION—JULIE SCOBELTZINE

Parisian costume designer Julie Scobeltzine fell into her career rather than planning it, although naturally careers often diverge from formal training. Her teachers from her graduate study in scenic design told her that out of the dozen students in a class, two would actually wind up working in the field. She agrees with the assessment. “I have a classmate who does store windows for high end jewelry, one who does illustrations, another who is a director. Everyone does different things, and I do costumes. One or two actually do set design.” In fact, although the majority of her career has been in costumes, she has begun designing both scenery and costumes for some of her shows.

Scobeltzine’s entry into the costume design field was something of a fluke. A year after graduation from the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, she sought an opportunity to broaden her training. She asked a classmate who was working as the assistant scenic designer on a production who the costume designer was, and if they might need an intern. Scobeltzine loved fabric, and had dabbled in making accessories, but her experience stopped there, so she was floored when she was asked to be the costume designer. The original costume designer had walked out on the project, and the set designer, who was her former professor, thought she was up to the task. She was frank about her inexperience, but she “had a meeting and no one asked me if I did or didn’t want to do it.” To implement the show, a (non-Disney) Beauty and the B...