![]() Part 1

Part 1

Sport media foundations![]()

Chapter 1

Sport and the media

A defining relationship

Overview

This chapter provides an overview of the nexus between the sport and media industries and outlines why sport and the media is an important field of study. It also defines sport, the media and the sport media nexus. The study of sport and the media is placed within a management context in order to explain its relevance to students of sport management, as well as sport managers and administrators in professional settings. This chapter also discusses the core drivers and major features of the sport media nexus in order to contextualize the material in subsequent chapters. Finally, this chapter provides an outline of the structure of the book.

Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter the reader should be able to:

- identify the core features of the sport media nexus;

- explain the core features of the sport media nexus and what underpins the relationship between the sport and media industries;

- understand the environment in which sport media is produced and consumed; and

- identify and explain the impact of each core driver of the sport media nexus.

Defining Sport and the Media

Prior to discussing the sport media nexus in detail, it is important to clarify what is meant by the terms sport and media. Although sport seems a superficially simple concept, it can be difficult for players, policy makers, managers, marketers and media alike to define. Depending on the context, sport might be interpreted in different ways, which will in turn influence whether and how it is mediated. Sport is best understood as having three core dimensions (Guttmann, 1978). First, it has a physical dimension. Second, it is competitive. Third and finally, it must be structured and rule bound. These dimensions might appear self-evident, but are worth noting because mediated sport is almost exclusively highly structured, highly competitive and very physical. In fact, sports such as football that emphasize, if not exaggerate, sport’s tripartite definition tend to dominate media coverage generally and television coverage in particular. On the other hand, sport that has low or non-existent levels of competition, structure and physicality are typically not attractive media products.

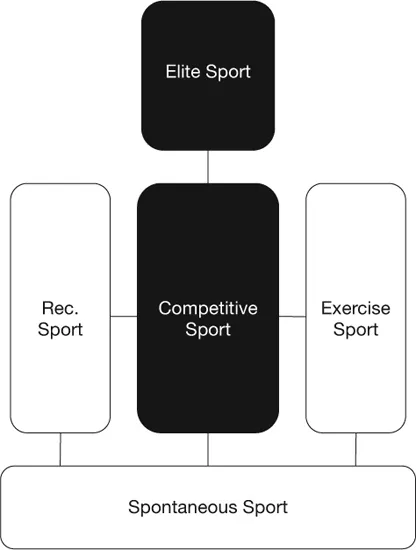

Figure 1.1 Sport typology

Figure 1.1 graphically represents a sport typology that illustrates different types of sport (Stewart et al., 2004). Spontaneous sport includes ‘pick-up’ sport that occurs by chance, which is often formalized as recreational sport. Recreational sport also includes extreme sport activities, as well as informal exercise. Exercise sport typically occurs in formalized settings, such an aerobics class or a gym workout. These first three categories, represented at the bottom and sides of Figure 1.1 are minor components of the sport media nexus. By contrast, competitive sport, which includes competitions below the elite level, receives media coverage and uses it to increase participation and financial capacity. This category includes sport played by amateurs at the community level through to high level school and university (college) sport. The final category, elite sport, is a major player in the sport media nexus. It comprises professional and semi-professional competitions and major events, from state and national championships through to the Olympic Games and FIFA World Cup.

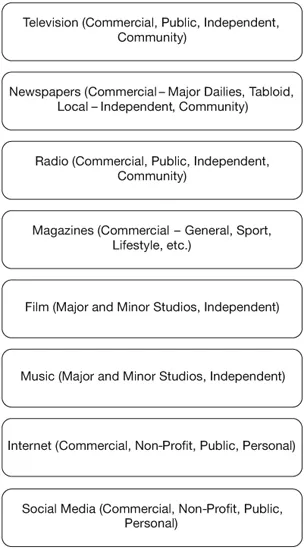

Figure 1.2 Elite and competitive sport levels

The final two categories of competitive and elite sport can be segmented further to demonstrate various tiers of activity, which are graphically represented in Figure 1.2. Figure 1.2 illustrates that competitive and elite sport cover the spectrum from local community level sport through to major global events. However, the diagram should not be interpreted as a hierarchical model of media interest or influence, as national leagues are often the most valuable sport media properties in the world.

Definitions of media are likely to make people think of vastly different and distinct occupations, people, organizations, texts and artefacts. The word media has come to mean a variety of things, in a similar fashion to sport, but in far greater complexity and breadth. According to Briggs and Burke (2005), ancient Greeks and Romans considered the study of oral and written communication important, as did scholars during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. It was not until the 1920s, however, that people referred to the concept of ‘the media’.

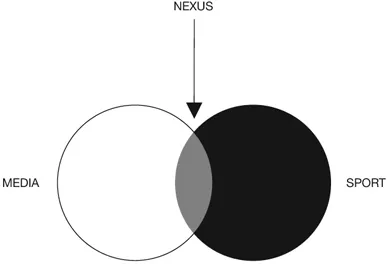

In contemporary usage the term media typically applies to two separate yet related elements. First, media refers to the means of mass communication, such as television, radio, newspapers or the internet. The various forms of communication and its types are illustrated in Figure 1.3. Importantly, within one form, such as television, there are many different types, such as commercial, public, independent and community. Furthermore, these types also have various levels. For example, a commercial media organization might own national television networks through to local stations that service a city or town. Second, media refers to those people employed within an organization such as a television station or newspaper, such as journalists and editors.

It is important to note that these two definitions span a variety of meanings that are context specific. In reference to broadcasting regulation, the media might be interpreted as the entire industry, which in turn might be national or global. In a discussion focusing on mergers and acquisitions, media might refer to a transnational corporation such as the Walt Disney Company. If the issue relates to the sale of broadcast rights, media might refer to different forms such as pay television, free-to-air television or the internet. Referring to the way in which a telecast of a game uses metaphors of war, the media might refer to the commentators. Finally, if the issue relates to the reporting of a scandal or crisis, media might refer to the specific article or broadcast in which it was first announced.

Figure 1.3 Media forms and types

The Nexus

The word nexus has its etymological roots in Latin and is a derivation of the word nectere, which means to bind. In essence a nexus is a connection, bond or tie between two or more things. The use of the word nexus in the subtitle of this book is deliberate. It is meant to signal that sport and the media are not two separate industries that have been juxtaposed coincidently. Rather, their evolution, particularly throughout the twentieth century, has resulted in them being inextricably bound together. Furthermore, the word nexus can refer to the core or centre. In this respect the use of the word nexus is meant to illustrate that the relationship between sport and the media is at the core of contemporary sport. Whether in reference to the way in which children are socialized through sport, the power of player associations and unions, or the use of talent identification programmes to foster elite development, the relationship between sport and the media is likely to reside at the very centre of the issue or problem. Thus, the sport media nexus refers to the relationship between sport and the media industry generally, the relationship between sport and specific media institutions such as television, the relationship between sport and media employees such as journalists and finally, the ways in which sport is presented in specific media texts, such as a radio broadcast or newspaper article.

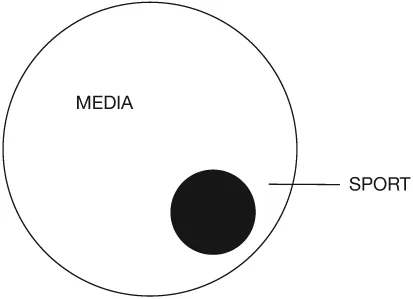

Figure 1.4 Sport media nexus

Figure 1.4 represents the sport media nexus in its most basic form. In this diagram the sport and media industries are represented as two equal partners and the nexus is the point at which they intersect. Although simple, Figure 1.4 also illustrates that not all of sport is part of the nexus. Rather, a proportion of sport is mediated. Similarly, not all media is sport related. However, this diagram does not represent the reality of much elite, professional and competitive sport, nor does it represent the importance of the media in daily sport consumption. In this respect the nexus is more accurately represented in Figure 1.5. Elite and professional sport is enveloped by the media. In this case sport might accurately be described as media sport because without the nexus or bond between the two the product would not exist. Consumers of sport must necessarily consume a mediated product. As the sport media nexus develops, the amount of sport consumed by the media increases (the circles in Figure 1.4 move closer together), as does the commercial importance of sport to the media (the black circle in Figure 1.5 grows larger).

Figure 1.5 Sport media nexus II

Sport Media Saturation

Every four years the world stops to watch football teams compete for a trophy called the World Cup. The final of the 2010 tournament in South Africa between Spain and the Netherlands was watched by 909 million people, while the number of viewers who watched a minimum of 20 consecutive minutes during the tournament was 2.2 billion throughout 214 nations, equivalent to nearly a third of the world’s population. The world also tunes in on a four year cycle to watch athletes strive to go higher, faster and stronger at the Summer and Winter Olympic Games; approximately 2.7 billion people watched at least 15 consecutive minutes of the London 2012 Olympic Games, while a total of 27.9 billion hours of London 2012 coverage was consumed by viewers worldwide. These mega-events compete for the attention of media consumers with year-long sport circuits, such as Formula One Racing, the Professional Golfers’ Association (PGA) European Tour and the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) Tour. These events and circuits, in turn, compete with national sport competitions that take place over the course of a season, with games played between one and four times per week. In the United States the nation stops every year for the Super Bowl, the championship game of the National Football League, when families and friends gather around television sets for what equates to a secular holiday. In 2013 the television audience was large enough for the television broadcaster to command US$4 million for each 30 second block of advertising time. It is clear from the examples above that there are large numbers of people watching sport on television, that there is a significant amount of sport broadcast on television and that televised sport is a primary vehicle for advertising. However, it is not only the major sport events and leagues that are broadcast by television, and television is not the only media form that is saturated by sport. In fact, from even a cursory examination of the media available in a single city or nation, it is readily apparent that sport has a significant presence across all media forms. Moreover, the media coverage of sport saturates daily life (Rowe, 1999), a phenomenon clearly illustrated by the way in which News Corporation sees itself in the following annual report excerpt.

Virtually every minute of the day, in every time zone on the planet, people are watching, reading and interacting with our products. We’re reaching people from the moment they wake up until they fall asleep. We give them their morning weather and traffic reports through our television outlets around the world. We enlighten and entertain them with such newspapers as The New York Post and The Times as they have breakfast, or take the train to work. We update their stock prices and give them the world’s biggest news stories every day through such news channels as FOX or Sky News. When they shop for groceries after work, they use our SmartSource coupons to cut their family’s food bill. And when they get home in the evening, we’re there to entertain them with compelling first-run entertainment on FOX or the day’s biggest game on our broadcast, satellite and cable networks. Or the best movies from Twentieth Century Fox Film if they want to see a first run movie. Before going to bed, we give them the latest news, and then they can crawl into bed with one of our best-selling novels from HarperCollins.

(News Corporation, 1999; cited in Law et al., 2002)

The relationship between sport and the media has become the defining commercial and cultural connection for both industries at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The media has transformed sport from an amateur pursuit into a hyper-commercialized industry, while sport has delivered massive audiences and advertising revenues to the media. The coverage of sport on television in particular has created a product to be consumed by audiences, sold by clubs and leagues, bought and sold by media organizations and manipulated by advertisers.

Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, the relationship between the media and sport industries intensified, to the point that they have become so entwined it is difficult to determine where one ends and the other begins. In an attempt to identify this process, as well as inform public and academic discourse, authors have combined the words sport and media in a variety of permutations. The common theme has been the creation of a new word or phrase that is representative of the nexus between these two commercial industries. In the 1980s and 1990s the sports/media complex and the media/sport production complex were both used to frame academic analyses of sport and the media (Jhally, 1984, 1989; Maguire, 1993, 1999). At the end of the twentieth century an edited collection was published with the title MediaSport (Wenner, 1998). Whether the words are juxtaposed, jammed together to create a new word, or separated by ‘and the’, it is clear that there is an imperative to characterize the process by which ‘sports, and the discourses that surround them’ became, as Boyd (1997: ix) suggested, ‘one of the master narratives of twentieth-century culture’.

The importance of this master narrative has been enhanced by the growing globalization of media corporations and the use of sport to consolidate established markets and exploit new ones, as well as the ways in which mediated sport is used to construct individual and collective identities. The extent to which this master narrative has become an assumed part of global, cultural, commercial and personal discourses is illustrated by Rowe’s (1999: 8) assertion that ‘a trained capacity to decode sports texts and to detect the forms of ideological deployment of sport in the media is, irrespective of cultural taste, a crucial skill’, and ‘an important aspect of a fully realized cultural citizenship’. In other words, the mediation of sport has become so pervasive that in order to live within the cultural and social world you must necessarily be able to understand the sport media nexus.

Sport Media Texts

At the end of the twentieth century Real (1998: 15) noted that ignoring sport media in contemporary society ‘would be like ignoring the role of the church in the Middle Ages or ignoring the role of Art in the Renaissance’. In other words, sport media is an omnipresent feature of contemporary societies and without the ability to analyse sport media we cannot hope to understand the societies in which we live. Real also argued that the saturation of media sport makes it difficult to analyse. Thus, the paradox is that understanding sport media is crucial to an understanding of broader society, but its place in society makes it almost impossible to do so. Because we are bombarded with images and sounds from sporting events and contests of the past, present and future, we are in a difficult, if not impossible place from which to establish a reference point. Often, and this is particularly true for people engaged in the study of sport or who are employed within the sport industry, people grow up immersed in sport and ...