- 124 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

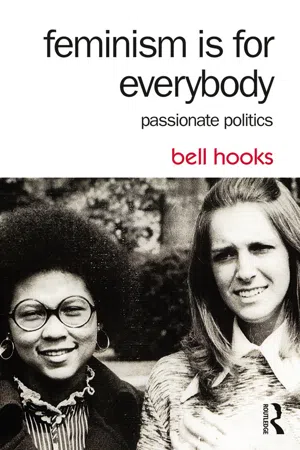

What is feminism? In this short, accessible primer, bell hooks explores the nature of feminism and its positive promise to eliminate sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression. With her characteristic clarity and directness, hooks encourages readers to see how feminism can touch and change their lives—to see that feminism is for everybody.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Feminism Is for Everybody by bell hooks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Feminist Politics: Where We Stand

10.4324/9781315743189-1

Simply put, feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression. This was a definition of feminism I offered in Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center more than 10 years ago. It was my hope at the time that it would become a common definition everyone would use. I liked this definition because it did not imply that men were the enemy. By naming sexism as the problem it went directly to the heart of the matter. Practically, it is a definition which implies that all sexist thinking and action is the problem, whether those who perpetuate it are female or male, child or adult. It is also broad enough to include an understanding of systemic institutionalized sexism. As a definition it is open-ended. To understand feminism it implies one has to necessarily understand sexism.

As all advocates of feminist politics know, most people do not understand sexism, or if they do, they think it is not a problem. Masses of people think that feminism is always and only about women seeking to be equal to men. And a huge majority of these folks think feminism is anti-male. Their misunderstanding of feminist politics reflects the reality that most folks learn about feminism from patriarchal mass media. The feminism they hear about the most is portrayed by women who are primarily committed to gender equality — equal pay for equal work, and sometimes women and men sharing household chores and parenting. They see that these women are usually white and materially privileged. They know from mass media that women’s liberation focuses on the freedom to have abortions, to be lesbians, to challenge rape and domestic violence. Among these issues, masses of people agree with the idea of gender equity in the workplace — equal pay for equal work.

Since our society continues to be primarily a “Christian” culture, masses of people continue to believe that god has ordained that women be subordinate to men in the domestic household. Even though masses of women have entered the workforce, even though many families are headed by women who are the sole breadwinners, the vision of domestic life which continues to dominate the nation’s imagination is one in which the logic of male domination is intact, whether men are present in the home or not. The wrongminded notion of feminist movement which implied it was anti-male carried with it the wrongminded assumption that all female space would necessarily be an environment where patriarchy and sexist thinking would be absent. Many women, even those involved in feminist politics, chose to believe this as well.

There was indeed a great deal of anti-male sentiment among early feminist activists who were responding to male domination with anger. It was that anger at injustice that was the impetus for creating a women’s liberation movement. Early on most feminist activists (a majority of whom were white) had their consciousness raised about the nature of male domination when they were working in anti-classist and anti-racist settings with men who were telling the world about the importance of freedom while subordinating the women in their ranks. Whether it was white women working on behalf of socialism, black women working on behalf of civil rights and black liberation, or Native American women working for indigenous rights, it was clear that men wanted to lead, and they wanted women to follow. Participating in these radical freedom struggles awakened the spirit of rebellion and resistance in progressive females and led them towards contemporary women’s liberation.

As contemporary feminism progressed, as women realized that males were not the only group in our society who supported sexist thinking and behavior — that females could be sexist as well — anti-male sentiment no longer shaped the movement’s consciousness. The focus shifted to an all-out effort to create gender justice. But women could not band together to further feminism without confronting our sexist thinking. Sisterhood could not be powerful as long as women were competitively at war with one another. Utopian visions of sisterhood based solely on the awareness of the reality that all women were in some way victimized by male domination were disrupted by discussions of class and race. Discussions of class differences occurred early on in contemporary feminism, preceding discussions of race. Diana Press published revolutionary insights about class divisions between women as early as the mid-’70s in their collection of essays Class and Feminism. These discussions did not trivialize the feminist insistence that “sisterhood is powerful,” they simply emphasized that we could only become sisters in struggle by confronting the ways women — through sex, class, and race — dominated and exploited other women, and created a political platform that would address these differences.

Even though individual black women were active in contemporary feminist movement from its inception, they were not the individuals who became the “stars” of the movement, who attracted the attention of mass media. Often individual black women active in feminist movement were revolutionary feminists (like many white lesbians). They were already at odds with reformist feminists who resolutely wanted to project a vision of the movement as being solely about women gaining equality with men in the existing system. Even before race became a talked about issue in feminist circles it was clear to black women (and to their revolutionary allies in struggle) that they were never going to have equality within the existing white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

From its earliest inception feminist movement was polarized. Reformist thinkers chose to emphasize gender equality. Revolutionary thinkers did not want simply to alter the existing system so that women would have more rights. We wanted to transform that system, to bring an end to patriarchy and sexism. Since patriarchal mass media was not interested in the more revolutionary vision, it never received attention in mainstream press. The vision of “women’s liberation” which captured and still holds the public imagination was the one representing women as wanting what men had. And this was the vision that was easier to realize. Changes in our nation’s economy, economic depression, the loss of jobs, etc., made the climate ripe for our nation’s citizens to accept the notion of gender equality in the workforce.

Given the reality of racism, it made sense that white men were more willing to consider women’s rights when the granting of those rights could serve the interests of maintaining white supremacy. We can never forget that white women began to assert their need for freedom after civil rights, just at the point when racial discrimination was ending and black people, especially black males, might have attained equality in the workforce with white men. Reformist feminist thinking focusing primarily on equality with men in the workforce overshadowed the original radical foundations of contemporary feminism which called for reform as well as overall restructuring of society so that our nation would be fundamentally anti-sexist.

Most women, especially privileged white women, ceased even to consider revolutionary feminist visions, once they began to gain economic power within the existing social structure. Ironically, revolutionary feminist thinking was most accepted and embraced in academic circles. In those circles the production of revolutionary feminist theory progressed, but more often than not that theory was not made available to the public. It became and remains a privileged discourse available to those among us who are highly literate, well-educated, and usually materially privileged. Works like Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center that offer a liberatory vision of feminist transformation never receive mainstream attention. Masses of people have not heard of this book. They have not rejected its message; they do not know what the message is.

While it was in the interest of mainstream white supremacist capitalist patriarchy to suppress visionary feminist thinking which was not anti-male or concerned with getting women the right to be like men, reformist feminists were also eager to silence these forces. Reformist feminism became their route to class mobility. They could break free of male domination in the workforce and be more self-determining in their lifestyles. While sexism did not end, they could maximize their freedom within the existing system. And they could count on there being a lower class of exploited subordinated women to do the dirty work they were refusing to do. By accepting and indeed colluding with the subordination of working-class and poor women, they not only ally themselves with the existing patriarchy and its concomitant sexism, they give themselves the right to lead a double life, one where they are the equals of men in the workforce and at home when they want to be. If they choose lesbianism they have the privilege of being equals with men in the workforce while using class power to create domestic lifestyles where they can choose to have little or no contact with men.

Lifestyle feminism ushered in the notion that there could be as many versions of feminism as there were women. Suddenly the politics was being slowly removed from feminism. And the assumption prevailed that no matter what a woman’s politics, be she conservative or liberal, she too could fit feminism into her existing lifestyle. Obviously this way of thinking has made feminism more acceptable because its underlying assumption is that women can be feminists without fundamentally challenging and changing themselves or the culture. For example, let’s take the issue of abortion. If feminism is a movement to end sexist oppression, and depriving females of reproductive rights is a form of sexist oppression, then one cannot be anti-choice and be feminist. A woman can insist she would never choose to have an abortion while affirming her support of the right of women to choose and still be an advocate of feminist politics. She cannot be anti-abortion and an advocate of feminism. Concurrendy there can be no such thing as “power feminism” if the vision of power evoked is power gained through the exploitation and oppression of others.

Feminist politics is losing momentum because feminist movement has lost clear definitions. We have those definitions. Let’s reclaim them. Let’s share them. Let’s start over. Let’s have T-shirts and bumper stickers and postcards and hip-hop music, television and radio commercials, ads everywhere and billboards, and all manner of printed material that tells the world about feminism. We can share the simple yet powerful message that feminism is a movement to end sexist oppression. Let’s start there. Let the movement begin again.

Consciousness-Raising: A Constant Change of Heart

10.4324/9781315743189-2

Feminists are made, not born. One does not become an advocate of feminist politics simply by having the privilege of having been born female. Like all political positions one becomes a believer in feminist politics through choice and action. When women first organized in groups to talk together about the issue of sexism and male domination, they were clear that females were as socialized to believe sexist thinking and values as males, the difference being simply that males benefited from sexism more than females and were as a consequence less likely to want to surrender patriarchal privilege. Before women could change patriarchy we had to change ourselves; we had to raise our consciousness.

Revolutionary feminist consciousness-raising emphasized the importance of learning about patriarchy as a system of domination, how it became institutionalized and how it is perpetuated and maintained. Understanding the way male domination and sexism was expressed in everyday life created awareness in women of the ways we were victimized, exploited, and, in worse case scenarios, oppressed. Early on in contemporary feminist movement, consciousness-raising groups often became settings where women simply unleashed pent-up hostility and rage about being victimized, with little or no focus on strategies of intervention and transformation. On a basic level many hurt and exploited women used the consciousness-raising group therapeutically. It was the site where they uncovered and openly revealed the depths of their intimate wounds. This confessional aspect served as a healing ritual. Through consciousness-raising women gained the strength to challenge patriarchal forces at work and at home.

Importandy though, the foundation of this work began with women examining sexist thinking and creating strategies where we would change our attitudes and belief via a conversion to feminist thinking and a commitment to feminist politics. Fundamentally, the consciousness-raising (CR) group was a site for conversion. To build a mass-based feminist movement women needed to organize. The consciousness-raising session, which usually took place in someone’s home (rather than public space that had to be rented or donated), was the meeting place. It was the place where seasoned feminist thinkers and activists could recruit new converts.

Importandy, communication and dialogue was a central agenda at the consciousness-raising sessions. In many groups a policy was in place which honored everyone’s voice. Women took turns speaking to make sure everyone would be heard. This attempt to create a non-hierarchal model for discussion positively gave every woman a chance to speak but often did not create a context for engaged dialogue. However, in most instances discussion and debate occurred, usually after everyone had spoken at least once. Argumentative discussion was common in CR groups as it was the way we sought to clarify our collective understanding of the nature of male domination. Only through discussion and disagreement could we begin to find a realistic standpoint on gender exploitation and oppression.

As feminist thinking, which emerged first in the context of small groups where individuals often knew each other (they may have worked together and/or were friends), began to be theorized in printed matter so as to reach a wider audience, groups dismantled. The creation of women’s studies as an academic discipline provided another setting where women could be informed about feminist thinking and feminist theory. Many of the women who spearheaded the introduction of women’s studies classes into colleges and universities had been radical activists in civil rights struggles, gay rights, and early feminist movement. Many of them did not have doctorates, which meant that they entered academic institutions receiving lower pay and working longer hours than their colleagues in other disciplines. By the time younger graduate students joined the effort to legitimize feminist scholarship in the academy we knew that it was important to gain higher degrees. Most of us saw our commitment to women’s studies as political action; we were prepared to sacrifice in order to create an academic base for feminist movement.

By the late ’70s women’s studies was on its way to becoming an accepted academic discipline. This triumph overshadowed the fact that many of the women who had paved the way for the institutionalization of women’s studies were fired because they had master’s degrees and not doctorates. While some of us returned to graduate school to get PhDs, some of the best and brightest among us did not because they were utterly disillusioned with the university and burnt out from overwork as well as disappointed and enraged that the radical politics undergirding women’s studies was being replaced by liberal reformism. Before too long the women’s studies classroom had replaced the free-for-all consciousness-raising group. Whereas women from various backgrounds, those who worked solely as housewives or in service jobs, and big-time professional women, could be found in diverse consciousness-raising groups, the academy was and remains a site of class privilege. Privileged white middle-class women who were a numeric majority though not necessarily the radical leaders of contemporary feminist movement often gained prominence because they were the group mass media focused on as representatives of the struggle. Women with revolutionary feminist consciousness, many of them lesbian and from working-class backgrounds, often lost visibility as the movement received mainstream attention. Their displacement became complete once women’s studies became entrenched in colleges and universities which are conservative corporate structures. Once the women’s studies classroom replaced the consciousness-raising group as the primary site for the transmission of feminist thinking and strategies for social change the movement lost its mass-based potential.

Suddenly more and more women began to either call themselves “feminists” or use the rhetoric of gender discrimination to change their economic status. The institutionalization of feminist studies created a body of jobs both in the world of the academy and in the world of publishing. These career-based changes led to forms of career opportunism wherein women who had never been politically committed to mass-based feminist struggle adopted the stance and jargon of feminism when it enhanced their class mobility. The dismantling of consciousness-raising groups all but erased the notion that one had to learn about feminism and make an informed choice about embracing feminist politics to become a feminist advocate.

Without the consciousness-raising group as a site where women confronted their own sexism towards other women, the direction of feminist movement could shift to a focus on equality in the workforce and confronting male domination. With heightened focus on the construction of woman as a “victim” of gender equality deserving of reparations (whether through changes in discriminatory laws or affirmative action policies) the idea that women needed to first confront their internalized sexism as part of becoming feminist lost currency. Females of all ages acted as though concern for or rage at male domination or gender equality was all that was needed to make one a “feminist.” Without confronting internalized sexism women who picked up the feminist banner often betrayed the cause in their interactions with other women.

By the early ’80s the evocation of a politicized sisterhood, so crucial at the onset of the feminist movement, lost meaning as the terrain of radical feminist politics was overshadowed by a lifestyle-based feminism which suggested any woman could be a feminist no matter what her political beliefs. Needless to say such thinking has undermined feminist theory and practice, feminist politics. When feminist movement renews itself, reinforcing again and again the strategies that will enable a mass movement to end sexism and sexist exploitation and oppression for everyone, consciousness-raising will once again attain its original importance. Effectively imitating the model of AA meetings, feminist consciousness-raising groups will take place in communities, offering the message of feminist thinking to everyone irrespective of class, race, or gender. While specific groups based on shared identities might emerge, at the end of every month individuals would be in mixed groups.

Feminist consciousness-raising for males is as essential to revolutionary movement as female groups. Had there been an emphasis on groups for males that taught boys and men about what sexism is and how it can be transformed, it would have been impossible for mass media to portray the movement as anti-male. It would also have preempted the formation of an anti-feminist men’s movement. Often men’s groups were formed in the wake of contemporary feminism that in no way addressed the issues of sexism and male domination. Like the lifestyle-based feminism aimed at women these groups often became therapeutic settings for men to confront their wounds without a critique of patriarchy or a platform of resistance to male domination. Future feminist movement will not make this mistake. Males of all ages need settings where their resistance to sexism is affirmed and valued. Without males as allies in struggle feminist movement will not progress. As it is we have to do so much w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- preface to the new edition

- introduction: come closer to feminism

- 1. feminist politics where we stand

- 2. consciousness-raising a constant change of heart

- 3. sisterhood is still powerful

- 4. feminist education for critical consciousness

- 5. our bodies, ourselves reproductive rights

- 6. beauty within and without

- 7. feminist class struggle

- 8. global feminism

- 9. women at work

- 10. race and gender

- 11. ending violence

- 12. feminist masculinity

- 13. feminist parenting

- 14. liberating marriage and partnership

- 15. a feminist sexual politic an ethics of mutual freedom

- 16. total bliss lesbianism and feminism

- 17. to love again the heart of feminism

- 18. feminist spirituality

- 19. visionary feminism

- index