- 442 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Game Theory and Exercises

About this book

Game Theory and Exercises introduces the main concepts of game theory, along with interactive exercises to aid readers' learning and understanding. Game theory is used to help players understand decision-making, risk-taking and strategy and the impact that the choices they make have on other players; and how the choices of those players, in turn, influence their own behaviour. So, it is not surprising that game theory is used in politics, economics, law and management.

This book covers classic topics of game theory including dominance, Nash equilibrium, backward induction, repeated games, perturbed strategie s, beliefs, perfect equilibrium, Perfect Bayesian equilibrium and replicator dynamics. It also covers recent topics in game theory such as level-k reasoning, best reply matching, regret minimization and quantal responses. This textbook provides many economic applications, namely on auctions and negotiations. It studies original games that are not usually found in other textbooks, including Nim games and traveller's dilemma. The many exercises and the inserts for students throughout the chapters aid the reader's understanding of the concepts.

With more than 20 years' teaching experience, Umbhauer's expertise and classroom experience helps students understand what game theory is and how it can be applied to real life examples. This textbook is suitable for both undergraduate and postgraduate students who study game theory, behavioural economics and microeconomics.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

How to build a game

Introduction

1 Strategic or Extensive Form Games?

1.1 Strategic/normal form games

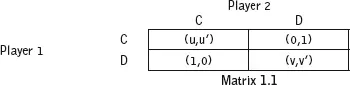

1.1.1 Definition

1.1.2 Story strategic/normal form games and behavioural comments

Prisoner’s dilemma

Chicken game, hawk-dove game, and syndicate game

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 HOW TO BUILD A GAME

- 2 DOMINANCE

- 3 NASH EQUILIBRIUM

- 4 BACKWARD INDUCTION AND REPEATED GAMES

- 5 TREMBLES IN A GAME

- 6 SOLVING A GAME DIFFERENTLY

- ANSWERS TO EXERCISES

- Index