Learning objectives

When you have finished reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- • appreciate the characteristics of underdevelopment in developing countries

- • understand why tourism is selected as a development option for developing countries

- • identify global tourism market shares and the changing nature of tourism

- • be familiar with the different approaches to tourism and development

Over the last 60 years, tourism has evolved into one of the world’s most powerful, yet controversial, socio-economic forces. As ever-greater numbers of people have achieved the ability, means and freedom to travel, not only has tourism become increasingly democratized (Urry and Larsen 2012), but also both the scale and scope of tourism have grown remarkably. In 1950, for example, just over 25 million international tourist arrivals were recorded worldwide. By 2012, that figure had surpassed the one billion mark (UNWTO 2013a), or, putting it another way, 2012 was the first year in the history of tourism that more than 1,000 million international cross-border movements (to be precise, 1,035 million) were made by people classified as tourists. Since then, international tourism has continued its inexorable growth, with international arrivals expected to have exceeded 1.1 billion in 2014. Moreover, if domestic tourism (that is, people visiting destinations within their own country) is included, the total global volume of tourist trips is estimated to be between six and 10 times higher than that figure. For example, in China alone, an estimated 2.61 billion domestic tourism trips, or more than double the total number of worldwide international arrivals, were made in 2011 (National Bureau of Statistics 2013). Little wonder, then, that tourism has been described as the ‘largest peaceful movement of people across cultural boundaries in the history of the world’ (Lett 1989: 265).

As participation in tourism has grown, so too has the number of countries that play host to tourists. Although just 12 nations accounted for almost half of all international arrivals in 2013, including traditionally popular destinations such as France, Spain, the USA and the UK, not only have a number of newer destinations, such as Turkey, Thailand and Malaysia, joined the list of top international tourist destinations, but also many others have claimed a place on the international tourism map. At the same time, numerous more distant, exotic places have, in recent years, enjoyed a rapid increase in tourism. Indeed, throughout the last decade, the Asia and Pacific region in particular has witnessed the highest and most sustained growth in arrivals globally, with a number of nations in that region, such as Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam, having experienced higher than world average growth in tourism (UNWTO 2014a). Such is the global scale of contemporary tourism that the WTO currently publishes annual tourism statistics for around 200 countries.

Reflecting this dramatic growth in scale and scope, tourism’s global economic contribution has also become increasingly significant. International tourism alone generated over US$1,159 billion in 2013 (UNWTO 2014a), and, if current forecasts prove to be correct, this figure could rise to US$2 trillion by 2020 (WTO 1998). By the end of the last century, tourism also represented the world’s most valuable export category, and although it subsequently fell back to fourth place, it is now, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council, the world’s fifth largest ‘industry’ in terms of direct GDP after financial services, mining, communication services and education. If indirect and induced economic contribution is included, then tourism overall generates more than $6.3 trillion annually, accounting for roughly 10 per cent of global GDP and employment (WTTC 2012).

Given this remarkable growth and economic significance, it is not surprising that tourism has long been considered an effective means of achieving economic and social development in destination areas. Indeed, the most common justification for the promotion of tourism is its potential contribution to development, particularly in the context of developing countries. That is, although it is an important economic sector, and frequently a vehicle of both rural and urban economic regeneration in many industrialized nations, it is within the developing world that attention is most frequently focused upon tourism as a developmental catalyst. In many such countries, not only has tourism long been an integral element of national development strategies (Jenkins 1991) – though often, given a lack of viable alternatives, an option of ‘last resort’ (Lea 1988) – but also it has become an increasingly significant sector of the economy, providing a vital source of employment, income and foreign exchange, as well as a potential means of redistributing wealth from the richer nations of the world. As the 2001 UN Conference on Trade and Development noted, for example, ‘tourism development appears to be one of the most valuable avenues for reducing the marginalization of LDCs from the global economy’ (UNCTAD 2001: 1).

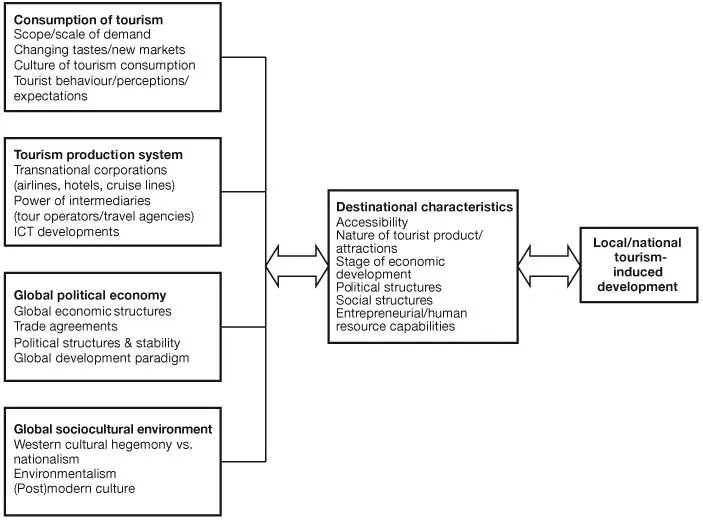

Importantly, though, the introduction of tourism does not inevitably set a nation on the path to development. In other words, many developing countries are, at first sight, benefiting from an increase in tourist arrivals and consequential foreign exchange earnings. However, the unique characteristics of tourism as a social and economic activity, the complex relationships between the various elements of the international tourism system and transformations in the global political economy of which tourism is a part all serve to reduce its potential developmental contribution. Not only is tourism highly susceptible to external forces and events, such as political upheaval (e.g. Egypt, where continuing political instability following the 2011 Arab Spring revolution resulted in tourism revenues in 2013 remaining approximately half the 2010 figure), natural disasters (e.g. the Indian Ocean tsunami in December 2004) or health scares (e.g. Mexico in 2009), but many countries have become increasingly dependent upon tourism as an economic sector, which by and large remains dominated by wealthier, industrialized nations (Reid 2003). Moreover, the political, economic and social structures within developing countries frequently restrict the extent to which the benefits of tourism development are realized. The factors that influence tourism’s potential developmental contribution are summarized in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Influences on tourism’s development

Many of these issues will be addressed throughout this book. However, the fundamental point is that there exists what may be referred to as a tourism development dilemma. That is, tourism undoubtedly represents a potentially attractive (and frequently the only viable) means of stimulating social and economic development in destination areas and nations, yet frequently that development fails to materialize, benefits only local elites or is achieved at significant economic, social or environmental cost to local communities. The dilemma for many developing countries, therefore, lies in the challenge of accepting or managing such negative consequences for the potential longer-term benefits offered by tourism development.

The purpose of this book is to explore these challenges and opportunities facing developing countries that pursue tourism as a development option. In so doing, it will critically appraise contemporary perspectives on tourism and development, and, in particular, sustainable tourism development, which, despite increasing doubts with respect to its legitimacy and viability, remains the dominant tourism development paradigm. However, the first task is to consider the concepts of underdevelopment/development and the relevance of tourism as a development option. It is with this that the rest of this introductory chapter is concerned.

Focus and definitions

As noted above, this book is primarily concerned with tourism in developing countries. The term ‘developing country’ is, of course, subject to wide interpretation and is often used interchangeably with other terminology, such as ‘Third World’ or ‘less-developed country’ or, more generally, ‘the South’. However, it usefully contrasts a country or group of countries (the ‘developing world’) with those that are ‘developed’, although, similarly, there is no established convention for defining a nation as ‘developed’. Nevertheless, the developed countries of the world, those that are technologically and economically advanced, that enjoy a relatively high standard of living and have modern social and political structures and institutions, are generally considered to include Japan, Australia and New Zealand in Oceania, Canada and the USA in North America, and the countries that formerly comprised Western Europe. Some commentators also include Israel, Singapore, Hong Kong and South Korea as developed countries.

Of course, categorizing the countries of the world as either ‘developed’ or ‘developing’ oversimplifies a complex global political economy. Not only does the developing world include countries that vary enormously in terms of economic and social development, with some, such as the BRIC group – Brazil, Russia, India and China – as well as the South East Asian ‘tiger’ economies, assuming an ever-increasingly important position in the global economy, but new trade or political alignments cut across the developed–developing dichotomy. For example, the so-called G20, or Group of Twenty, established in 1999, promotes dialogue between industrialized and those emerging-market countries not considered to be adequately included in global economic discussion and governance (see www.g20.org). The group comprises Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, the UK and the USA, countries that account for 90 per cent of global GDP and 80 per cent of world trade.

Nevertheless, for the purposes of this book, the term ‘developing country’ embraces all nation states that are not generally recognized as being developed, including the transitional economies of the former ‘Second World’ and contemporary, centrally planned economies. Though covering an enormous diversity of countries that may demand subcategorization, this focus nevertheless reflects Britton’s (1982) metropolitan/periphery political-economic model, which, arguably, still defines the structure of international tourism, though less so than in the past. That is, despite the increasing numbers of developing countries with significant tourism sectors relative to both their national economies and global tourism more generally, recent figures reflect the continuing domination of the developed world in terms of both international arrivals and receipts; in 2012, the 32 developed countries collectively accounted for approximately 49 per cent of global arrivals and 54 per cent of global receipts, albeit a reduction on the 2002 figures of 54 per cent and 61 per cent, respectively. However, according to the UNWTO (2014b: 13), ‘By 2030, the majority of all international tourist arrivals (57 per cent) will be in emerging economy destinations’, pointing to a shift in the balance of world tourism and, indeed, the importance of considering tourism and development in these countries as a whole.

The terms ‘tourism’ and ‘development’ also require definition. Regarding tourism, most introductory tourism texts consider the issue in some depth (for example, Sharpley 2002; Fletcher et al. 2013), while, generally, many definitions have been proposed. However, these may be classified under two principal headings:

Technical definitions attempt to identify different categories of tourist for statistical or legislative purposes. Various parameters have been established to define a tourist, such as minimum (one day) and maximum (one year) lengths of stay, minimum distance from home travelled (160 km) and purpose, such as ‘holiday’ or ‘business’ (WTO/UNSTAT 1994), though a useful overall definition has been proposed by the UK’s Tourism Society:

Tourism is the temporary short-term movement of people to destinations outside the places where they normally live and work, and their activities during their stay at these places; it includes movement for all purposes, as well as day visits or ...