Energy, of course, is used by everyone, in all parts of the global economy, although its form varies considerably. The poorest people use ‘local fuels’ such as wood and manure to cook basic ingredients and to keep warm, while Western societies use energy, predominantly from fossil fuels, to extract resources and manufacture products, for transportation and to provide services (heat, cooling and hot water) at work and in our homes. But this increasing demand for energy is leading to many important global challenges, in particular climate change, fuel poverty and energy security.

1.2.1 Climate change

Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and since the 1950s, many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia… . It is extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century.

(IPCC, 2013, p. 2)

Human activity, resulting in the emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the combustion of fossil fuels, is augmenting the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases (GHGs) at an unprecedented rate. The accumulation of atmospheric concentrations of all GHGs has increased since the inception of the Industrial Revolution in 1750 (IPCC, 2013), with global CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion and cement production increasing on average by 2.5 per cent per year over the past decade (Friedlingstein, 2014). The impacts on human society will be widespread and will involve destructive weather events, the disruption of food production and impacts on human health (IPCC, 2014a). While there is still debate over the potential future impacts of climate warming, a 2 ºC rise has become the accepted threshold beyond which climate change effects will be ‘dangerous’ (Copenhagen Accord, 2009).

However, there is a ‘significant gap’ between the current trajectory of global GHG emissions and the ‘likely chance of holding the increase in global average temperature below 2 ºC or 1.5 ºC above pre-industrial levels’ (UNFCCC, 2011, quoted in Peters et al., 2012, p. 1). To keep temperature increases below 2 ºC is likely to require challenging global CO2 mitigation rates of over 5 per cent per year, partly because of the likelihood of increased emissions in some regions, in addition to meeting the long-term carbon quota (Raupach et al., 2014). Moreover, if there is a delay in starting mitigation activities, the target of remaining below 2 ºC becomes even more difficult, if not unfeasible. Many of these higher rates of mitigation rely on negative emissions, using emerging technologies such as carbon capture and storage possibly linked to bioenergy, which have high risks due to potential delays or failure in their development and large-scale deployment (Peters et al., 2012). As a consequence of the challenges of achieving these mitigation rates, the likelihood of keeping climate change within 2 ºC is being increasingly called into question, with a trajectory of 4, 5 or even 6 ºC seeming more likely (Jordan et al., 2013).

Nevertheless, society’s principal response to the challenge of climate warming needs to be one of mitigation, with urgent and radical moves towards decarbonisation (Anderson et al., 2008). The global political response towards achieving long-term reductions in emissions began with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1994 and the first legally binding protocol, the Kyoto Protocol, adopted in 1997 and entered into force in 2005. Under the Kyoto Protocol, governments committed to reduce their country’s emissions by a target date. The UK, for example, committed to reduce its emissions by 12.5 per cent from 1990 levels by 2012; this it easily achieved, mainly as a result of the economic recession and exporting its carbon footprint (i.e. many products used in the UK are manufactured in other countries, so the associated carbon emissions are not attributed to the UK).

Globally, carbon emissions nearly doubled from 1973 (15,633 mtCO2) to 2012 (31,734 mtCO2) (OECD/IEA, 2014). Carbon dioxide emissions from global fossil fuel combustion and cement production have increased every decade over the last 50 years, starting from an average 3.1 ± 0.2 GtC/yr in the 1960s, to 8.6 ± 0.4 GtC/yr during 2003–2012 (Le Quéré et al., 2014). (Note that these values are expressed as carbon rather than carbon dioxide.) It might have been expected that the global financial crisis in 2008–2009, with its impact on economic activities, would have slowed the rate of growth in emissions. Its effects were short-lived, however, owing to a substantial growth in the emerging economies, a return to emissions growth in developed economies and an increase in the fossil-fuel intensity of the world economy (Peters et al., 2012). In terms of CO2 emissions per person, the CO2 emissions in 2012 were 1.4 tC per capita/yr globally, and 4.4 (USA), 1.9 (China), 1.9 (EU) and 0.5 (India) tC per capita/yr (Le Quéré et al., 2014).

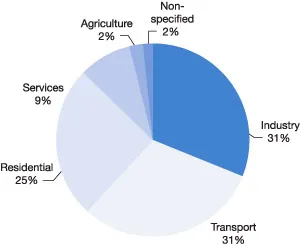

Carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes contributed to approximately 78 per cent of the total GHG emissions during the period 2000–2010, while the use of buildings contributed 19 per cent of GHG emissions (2010) (IPCC, 2014b). Note that the emissions associated with the construction of buildings is included in the industrial sector. Even though many countries are seeking ways to meet carbon emission targets by reducing their energy demand, the energy demand from buildings is projected to double and CO2 emissions to increase by 50 to 150 per cent by 2050 in baseline scenarios. However, there are considerable opportunities to reduce this demand using energy-efficient technologies, policies and know-how. In developed countries it is also considered that up to 50 per cent of energy demand could be reduced through behavioural and lifestyle changes by 2050 (IPCC, 2014b).

1.2.2 Fuel poverty

Fuel poverty is a term used in the UK and some other EU countries to describe the lack of access to energy. In the United States ‘energy insecurity’ is used, and in 20 OECD countries ‘lacking affordable warmth’ (Liddell and Morris, 2010). There is also conflicting use of the terms ‘energy’ and ‘fuel poverty’ within the EU (Thomson and Snell, 2013a), with ‘energy poverty’ being the more common term in developing countries. All these terms, however, focus on a lack of access to adequate, ‘clean’ (i.e. with low particulate emissions) energy, whether this is due to (1) energy resources not being available, (2) the lack of...