eBook - ePub

Strategies of Sex and Survival in Female Hamadryas Baboons

Through a Female Lens

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book describes the first field study focusing on the behavior of hamadryas females in the wild. In its attempt to rectify the male-biased view of hamadryas baboon behavior that has persisted over the decades, this book suggests that female behavior contributes more to hamadryas social organization than has previously been assumed and that females may, in fact, be acting in their own best interests after all. For upper-level undergraduate courses on primate behavior and ecology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Strategies of Sex and Survival in Female Hamadryas Baboons by Larissa Swedell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER

1

Hamadryas Baboons: The Male as Leader and Icon

Since the days of the ancient Egyptians, hamadryas baboons have intrigued scientists and laypersons alike. The majestic lion-like mane of the hamadryas male is the first thing one notices upon observing a group of hamadryas baboons, and it is thus no surprise that males have occupied the primary position in both cultural and scientific representations of the species. The role of the more unassuming hamadryas baboon female, on the other hand, has been relatively neglected, both by the ancient Egyptians and by twentieth-century scientists.

HAMADRYAS BABOONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

King Tut’s tomb is surrounded by a painted wall mosaic of hamadryas baboons. As such a prominent location in a tomb implies, hamadryas baboons occupied a prominent position in ancient Egyptian society. Although not native to Egypt, baboons were brought there in predynastic times from the Horn of Africa. Like many other animals, hamadryas baboons were often kept as pets and were highly regarded by the ancient Egyptians, in both secular and sacred ways (Germond & Livet 2001). It is due to this association with ancient Egyptian mythology that the hamadryas are often called “sacred baboons” in northeastern Africa.

In ancient Egypt, the hamadryas baboon was considered to be one of the mortal incarnations—in addition to the ibis, an elegant bird—of Thoth, the god of wisdom and scholars (Ions 1982). It was Thoth who was responsible for weighing and judging the souls of the dead, and this role is reflected in Egyptian illustrations in which a hamadryas baboon is often depicted sitting on the edge of a scale.

One ancient Egyptian myth shows an interesting parallel to the natural behavior of hamadryas males. Apparently Tefnut, the sister and wife of Shu, once escaped into the Nubian desert in the shape of a lioness. Shu and Thoth were then sent by Ra, the sun god, to retrieve Tefnut. After transforming themselves into baboons, Shu and Thoth tracked down Tefnut in the desert and Thoth then won her over with his magical powers. Although Tefnut ultimately married Shu, in some versions of the story it is said that she instead married Thoth on their return trip from Nubia (Ions 1982).

Akin to Thoth’s role in the retrieval of Tefnut, hamadryas baboon males are talented at finding and retrieving females. As discussed in more detail later, male hamadryas aggressively herd females out of their natal family units into new family units and, in many ways, can be seen as controlling female behavior. It has even been suggested that one of the primary mechanisms leading to the formation of the hamadryas-anubis hybrid zone in Awash National Park was repeated kidnapping of anubis baboon females by hamadryas males (Nagel 1973; Kummer 1995), a behavior that may have been observed by the ancient Egyptians as well. (It is actually unlikely that such abductions have contributed significantly to the formation of hybrid groups; rather, migration by hamadryas males appears to have played a larger role; see Phillips-Conroy et al., 1992.)

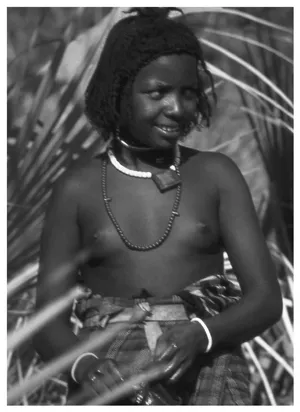

HAMADRYAS BABOONS AND THE AFAR PEOPLE

Also found in the semidesert regions of eastern Ethiopia and northern Somalia are the Afar people, nomadic pastoralists who subsist largely on the milk and meat of their livestock (Getachew 2001). Frequently at war with other nomadic tribes in the area, the Afar are reputed for their traditional rite of passage to manhood whereby a male member of an enemy tribe is killed and his testicles are worn on a string around the neck. Fortunately for the baboons, Afar hunting does not usually extend to wild animals, nor do the Afar take much notice of the baboons in general except during droughts or other times when they use the same resources, such as doum palm nuts and water holes. The Afar do have their myths about the baboons, though, one of which was told to Getenet Wondimu Hailemeskel by an elderly Afar man named Hamedu Ture who lived in Doho, a small village north of Filoha.

As the story goes, hamadryas baboons used to be human beings who lived much like the Afar do today. They lived in a beautiful area surrounded by trees, open grassland, and a river. Each family, inhabiting a separate hut in the village, consisted of a husband, his several wives, and their children. They had no knowledge of or belief in a higher being or God, but instead worshipped elements of nature such as large trees and rocks.

Afar nomads, such as this young girl, frequent the Filoha area. (Photo by Barbara Swedell)

The hamadryas people subsisted mainly on fish, which they would catch each day at the nearby river. One Sunday at the river, an odd-looking man came to them, introduced himself as Sheik Hussein, and asked them why they were fishing on Sunday. He explained to them that God had ordered all human beings not to work on Sundays, and that by doing so the hamadryas were deliberately violating God’s orders. The hamadryas wondered why this was the case, and Sheik Hussein explained further that God was their lord and that they were the slaves of God. He created everything in six days and rested on Sunday, so they must, in return, celebrate God on this day. Sheik Hussein added that the hamadryas must obey these orders in the future and cease to fish on Sundays. The hamadryas agreed.

Unfortunately, none of the hamadryas kept their promise. Several Sundays later, Sheik Hussein appeared again and reprimanded them for disobeying his orders. He told them that they had broken their promise and must now be punished. He then declared his punishment, which was that the hamadryas must leave their villages and walk on four limbs in the wild, spending their nights on cliffs and in the trees instead of in their huts. They would no longer be human beings, but would be one of the social animals that lives in the wild, fighting with one another in groups. And so it was that the hamadryas became baboons and henceforth inhabited the forests and open grasslands, feeding on grass and fruits from trees and drinking at the river.

HAMADRYAS DISTRIBUTION AND TAXONOMY

Today, hamadryas baboons inhabit only the Horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, Djibouti, and Eritrea) and the southwestern corner of the Arabian peninsula in Yemen and southwestern Saudi Arabia (Kummer 1968a; Kummer et al. 1981; Wolfheim 1983; Biquand et al. 1992a; Al-Safadi 1994; Kamal et al. 1994; Zinner et al. 2001a). Much of their distribution consists of semiarid, desert-like regions, and it is for this reason that hamadryas have yet a third common name, “desert baboon.” This label distinguishes the hamadryas ecologically from other baboons: the “savanna baboons” of the grasslands in east and southern Africa and the “mountain baboons” of the Drakensberg in South Africa.

Distributed across the African continent are five main forms of baboons, commonly known as olive (or anubis), yellow, chacma, Guinea, and hamadryas. While they are commonly referred to as separate species and are often classified as either five species (e.g., Hill 1967; Napier & Napier 1967, 1985; Hayes et al. 1990) or two species (Thorington & Groves 1970; Kingdon 1974; Smuts et al. 1987) by behavioral ecologists and others, they in fact hybridize at the borders between their respective distributions (Jolly 1993). This lack of reproductive isolation, and in particular the well-documented hybrid zone between hamadryas and anubis baboons in Ethiopia (e.g., Phillip s-Conroy & Jolly 1986)—coupled with genetic evidence suggesting a lack of differentiation among (sub)species (Williams-Blangero et al. 1990; Hapke et al. 2001)—suggests that a single-species classification may be most appropriate (Jolly 1993; Disotell 2000). Most tax-onomists, therefore, today agree that all baboons should be placed within a single species—which, according to the rules of nomenclature, must be called Papio hamadryas as that was the first name used—with five or more phenotypically and geographically distinct subspecies (e.g., Szalay & Delson 1979; Groves 1993; Jolly 1993). While baboon taxonomy is still controversial and no one classification is universally accepted, I will follow Groves (1993) and Jolly (1993) in adopting the single-species classification in this book.

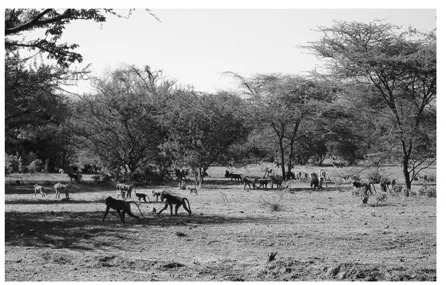

HAMADRYAS SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

Hamadryas baboons are unique among primates with regard to their complex, multilevel social system and their extreme male-dominated society, both of which have been viewed as adaptations to the harsh, semi-desert environment in which they evolved and in which most live today (Kummer 1968a, 1968b; 1971b). Three main levels of organization have been described as characterizing hamadryas baboon society (Kummer & Kurt 1963; Kummer 1968a, 1968b; Abegglen 1984), as follows: Troops are large aggregations (usually over 100 individuals) that assemble at sleeping sites but do not otherwise function as cohesive social groups. Each troop includes one or more bands, whose members travel together during the day and coordinate their movements. The band is probably the social grouping analogous to the “group” or “troop” of other monkeys such as macaques, mangabeys, or olive baboons. Adult members of different bands rarely interact, and when they do interact, they usually do so agonistically. Even when two or more bands share a sleeping cliff, each band travels and forages separately from other bands during the day.

Within each band are a number of one-male units (OMUs). Each OMU consists of one adult “leader” male, one or more adult females, their offspring (to about the age of two to three years, at which point juvenile males no longer associate regularly with their natal OMU and juvenile females have been incorporated into another OMU), and sometimes one or more “follower” males. Also within bands are “solitary” males, males who are neither leaders of OMUs nor are attached to an OMU as a follower male. Solitary males, as well as older juvenile males, move freely within the band, do not associate regularly with any one OMU, and interact mainly with other solitary males and juveniles.

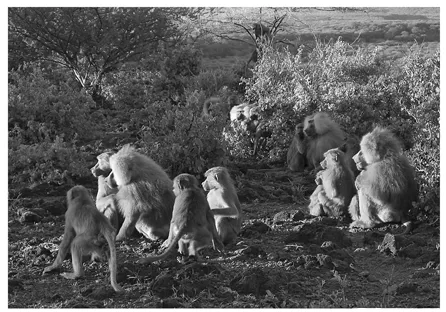

Bands of hamadryas baboons typically travel and forage as a coordinated unit. (Photo by the author)

Cohesion of hamadryas one-male units is maintained by aggressive herding behavior of leader males, who threaten and bite females that become spatially or socially separated from the rest of the unit. A leader male appears to have nearly exclusive sexual access to the females of his unit, whereas follower males copulate relatively rarely and appear to be awaiting future reproductive opportunities (Kummer 1968a; Abegglen 1984; Stammbach 1987). Unlike in other baboons, males rarely interact aggressively over estrous females or attempt to copulate with another male’s females, but instead appear to “respect” other males’ “possession” of females and do not typically interact with females when they already “belong to” another male of the same band—regardless of the relative dominance rank between the two males (Kummer 1968b, 1971a; Kummer et al. 1974). When a leader male loses his females, the recipient is often a younger follower male of his own unit (Kummer et al. 1978; Abegglen 1984). In fact, older leader males have been reported to voluntarily relinquish their females to younger followers, with whom they have developed a friendly relationship and to whom they might be related (Kummer 1968a; Abegglen 1984).

Four one-male units sitting at the top of the Wasaro cliff just after dawn, responding to a scream nearby.

Abegglen (1984) observed a fourth level of social organization between that of bands and one-male units. In Band I near Erer Gota, Abegglen noticed that certain males, both solitary and with females, associated more frequently with one another than they did with other males. Abegglen saw obvious physical resemblances among these males, proposed that they were close kin, and called their associations clans. (Unfortunately, Abegglen’s proposition was never confirmed with genetic data because samples were never obtained from these males.) Abegglen reported that OMUs within each of these clans were spatially distinct from OMUs in other clans, both during daily travel and on the sleeping cliffs. Males tended not to transfer out of their natal clan, and males of the same clan tended to have affiliative social relationships with one another, characterized by grooming among solitary males and formalized, stereotypical “notifying” behavior (whereby one male quickly approaches, looks at, presents to, and then leaves another male) among leader males and between leader males and their followers (Kummer 1968a; Stolba 1979; Abegglen 1984). The clan structure has also been observed by Stolba (1979) in other bands near Erer Gota.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH ON HAMADRYAS BABOONS

Some of the earliest research on hamadryas baboons was conducted by Sir Solly Zuckerman in the 1920s and 1930s on a group of captive hamadryas baboons at the London Zoo (Zuckerman & Parkes 1930, 1939; Zuckerman 1932). Zuckerman saw social behavior, sexuality, and aggression as being intrinsically linked. He drew these conclusions from his observations of frequent and persistent fighting among the hamadryas males over access to females and the resulting high incidence of injury and death. Zuckerman believed that animal behavior was in no way modified by captivity, and that the high levels of aggression he observed among hamadryas in captivity were no different from patterns of behavior in the wild. We now know, of course, that such high levels of aggression are unusual, both among hamadryas and among other wild primates, and were more likely attributable to the fact that over a hundred baboons were confined to a 100 × 60 ft. enclosure, rather than the 300 × 300 ft. area that a band normally occupies in the wild (see Chapter 4).

A more accurate view of hamadryas behavior came from the pioneering work of Hans Kummer and Fred Kurt in 1960 near Erer Gota, Ethiopia, about 180 km northeast of the Awash National Park (see Figure 1-1). Kummer and Kurt spent 12 months surveying baboon troops and collecting behavioral data on several bands in the Erer Gota area. It was this research that first documented the multilevel social structure of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Hamadryas Baboons: The Male as Leader and Icon

- 2 Reproductive Strategies in Primates: Conflicts between the Sexes

- 3 Study Site, Subjects and Methods

- 4 Hamadryas Behavioral Ecology: Negotiating a Hostile Land

- 5 Hamadryas Social Organization: The Haves and the Have-Nots

- 6 Reproduction and Sexual Behavior

- 7 Friendship among Females

- 8 Dispersal and Philopatry in Hamadryas Baboons

- 9 Female Strategies in a Male-Dominated World

- 10 Summary of Findings

- Epilogue

- Appendix I

- References Cited

- Index