![]()

Part I

Liberal origins

![]()

1 Old spirit of capitalism

The political-economic context of management accounting

1.1 Contextualizing the old logic of management accounting: pillars of analysis

Learning management accounting as a social science entails moving beyond its techno-managerial contents to see it as a socio-cultural and political phenomenon. For this purpose, it needs to be located within its wider context. In a broader sense, capitalism is management accounting’s political economic context; it is the political system in which management accounting is located. Hence, the connection between management accounting and capitalism is one of the key themes that we need to pay our attention to here. At the outset, this connection is dialectical. On the one hand, it was the birth of capitalism that gave rise to management accounting. In different ways, early developments in industrial capitalism in late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries necessitated management accounting. Its subsequent neoliberal developments since the 1980s underlie the recent evolutions in management accounting into what is now coming to be known as strategic management accounting. On the other hand, management accounting is one of the key technologies that facilitates the functioning and growth of capitalism. Management accounting, as a mundane set of organizational practices, provides calculative techniques and practices to materialize the ideology of capital accumulation. It is this dialectical connection between capitalism and management accounting which will provide our focal attention in understanding management accounting as a socio-political phenomenon.

During the recent past, we have seen a historical rupture in capitalism. Sociologists and organizational theorists call this rupture a ‘new spirit of capitalism’ (Boltanski and Chiapello 2007; Du Gay and Morgan 2014). They see capitalism entering a new phase of development encompassing: political-economic logics of neoliberalism; market dynamics of globalization; and technological shifts of digitalization, networking, and virtualization. As a corollary to this, we also see certain changes in management accounting practices and techniques. A wide spectrum of ‘new’ management accounting techniques and practices ranging from Activity-Based Costing (ABC) and Balanced Scorecards (BSC) to ‘big data analytics’ are now in circulation. However, the focus of this chapter is neither the new spirit of capitalism nor the ‘new’ management accounting. Instead, the focus here is on the ‘old spirit of capitalism’ and the traditional mode of management accounting. This is because, we believe, the old provides the comparative basis to understand and explain the new, which we will be doing in the second part of this book.

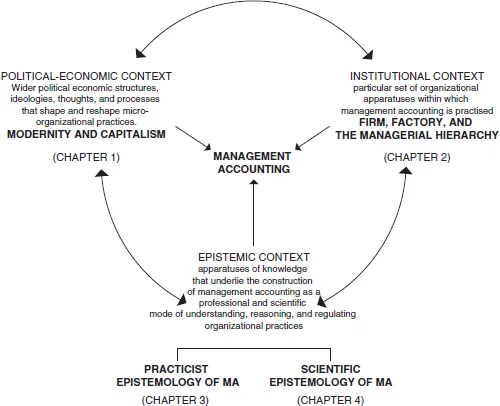

We conceptualize the management accounting ‘context’ in three interrelated analytical pillars: political-economic, institutional, and epistemic (see Figure 1.1). The political-economic context refers to the wider systemic apparatuses that frame micro-organizational practices. Modernity and industrial capitalism designate the political economic system with which traditional management accounting originated and evolved. Despite their theoretical differences, accounting scholars in general agree that the origin and development of management accounting is directly related to the evolution of modern industrial capitalism (e.g. Hopper and Armstrong 1991; Johnson and Kaplan 1987a, 1987b; Kaplan 1984; Loft 1995). As such, management accounting embraces a particular political economic and historical logic pertaining to modernity and industrial capitalism. This chapter explores this political-economic and historical logic of management accounting.

Figure 1.1 Contextualizing management accounting: the old logic

The institutional context refers to a much narrower scope: the particular set of ‘organizational apparatuses’ within which management accounting is practised. We see three interrelated organizational apparatuses constituting the institutional context: (1) the factory-based organization of labour, (2) the managerial hierarchy or bureaucracy, and (3) the organization of capital into firms. As such, we take factory, bureaucracy, and the firm as the major elements of the institutional context of conventional management accounting. Chapter 2 articulates how these elements contextualized management accounting.

Epistemic context refers to the apparatuses of knowledge that underlie the construction of management accounting as a professional and scientific mode of understanding, reasoning, and regulating organizational practices. There are two distinct but interrelated apparatuses here. First is the professional apparatus which we call ‘practicist epistemology’ of management accounting and will be discussed in Chapter 3. The second is what we call ‘scientific epistemology’ of management accounting, which will be dealt with in Chapter 4.

This chapter is organized as follows:

- Section 1.2 introduces the concepts of modernity, modernism, and capitalism. While explaining their meaning, this section articulates how their emergence and growth are related to the development of human sciences or ‘disciplines’, including management accounting, and how such disciplines constitute the basis of control and regulation in modern societies.

- Section 1.3 takes this discussion into a deeper level to explain modernity as a transformation in the mode of government. This transformation was from sovereignty to governmentality. Hence Foucault’s notion of ‘governmentality’ is central to this discussion. Macro and micro dimensions of governmentality are discussed in two distinct but interrelated terms: biopolitical accounting and disciplinary accounting.

- Section 1.4 brings us to capitalism. Capitalism is discussed as the ideological and structural context of management accounting. Liberal economic democracy was the political ideology of modernity. Hence attention is paid to how it transformed economic relationships and structures into a capitalistic social order where accumulation of capital became the dominating principle of organizing social relations. The notion of ‘freedom’ is discussed here in terms of free markets, free labour, and socialized capital. The role of accounting is discussed with special attention being given to the return on capital employed as the accounting signature of capitalism.

- Finally, Section 1.5 summarizes and concludes the chapter with an overall discussion on the accounting implications of modernity and capitalism.

1.2 Political base of traditional management accounting: modernity, modernism, and capitalism

Capitalism, modernism, and modernity are interrelated concepts that accounting academics use to explain the origin and evolution of management accounting. Indeed, these concepts are complex, debatable, and hence difficult to define. However, for the purpose of contextualizing management accounting, we define capitalism as a social order in which freedom in (and through) the market, the socialized private ownership of capital, and the perpetual accumulation of private capital are the dominating principles of organizing social relations. Modernity, on the other hand, is the historical phase during which this social order was established in the Western world. Modernism, on the other hand, refers to the political-economic thought and the cultural movement that characterized the period of modernity. Modernity is the historical phase or trajectory; modernism is the political cultural thought behind that historicity; and capitalism is the economic, structural, and organizational manifestation of that thought.

The age of modernity is the epoch that began with the Enlightenment, the philosophical movement which dominated the world of ideas in Europe in the eighteenth century. This was the period where rationalism started to become a political phenomenon and a dominating social movement. Philosophers like René Descartes and Immanuel Kant introduced the idea that it is through rational reasoning that humans can establish a foundation of universal truth. People like Isaac Newton then championed the idea that science should be the modus operandi of this rational reasoning. Political leaders of modernity then connected this scientific rational reasoning with the idea of social progresses to transform governments. Progressive social transformation based on scientific rational reasoning then became a political imperative. Political and philosophical notions such as liberty, progress, reason, equality, tolerance, fraternity, and so on, became important normative elements of the cultural-political and economic landscape. This was indeed an ideological and political movement against the abuses of power by sovereign states. And it was a movement that questioned religious orthodoxy. It is this ideological and political repositioning of the West based on a notion of progress through scientific reasoning, individual freedom, and equality which we broadly call modernism. These modernist developments in political thought fed into not only dramatic political transformations such as French and American democratic revolutions but also into a whole trajectory of overarching and long-lasting socio-economic transformations such as industrialization, urbanization, colonization, human sciences, educational establishments, and changes in occupations and property ownership. After all, modernity and modernism were ‘great transformations’ (cf. Polanyi 1944) that changed the political and economic landscape of the Western, and consequently, non-Western civilizations.

Scientific reasoning (vis-à-vis religious reasoning) thus became politically and culturally acceptable and significant. It became the basis of providing meaning for human actions. Human agency and freedom were connected with the capacity to rationalize these actions through scientific reasoning. This provided the political cultural impetus for the growth of a diverse set of human sciences, including accounting. Such human sciences not only brought up specific schemas of scientific reasoning but also made the ‘disciplinary knowledge’ the dominating apparatus of power in modern societies (Foucault 1995). People were controlled, disciplined, and regulated through an emerging set of disciplines which penetrated every aspect of social being. This was indeed the formation of a new form of government where human sciences played governing roles. This was a new rationality or mentality of government which also brought up management accounting as a technology of government.

1.3 Governmentality: political changes of modernity and management accounting

Governmentality is the term that Foucault, a well-known French philosopher and historian, uses to describe this new rationality of government. Governmentality differs from the pre-modern sovereign forms of government (i.e. sovereignty) due to the nature of the power on which it is based. Governmentality runs on two notions of power: biopower (or biopolitics) and disciplinary power. In governmentality, people are governed not so much by the exercise of the sovereign power of the state but by the diffused and distributed use of biopower and disciplinary power.

These two modes of modern power are, in many ways, different from the sovereign or royal power that any agent of sovereignty (such as king, queen, prince, magistrate, sheriff, etc.) exercised. Sovereign power was centralized in the state (i.e. the sovereign) and was often passionate, violent, and repressive. Its deployment was deductive and took physical form, such as banning, exclusion, repression, torture, or execution. And it was commanding and demanding: it commanded and demanded a sacrifice from the subject to save the throne. It was based on the pre-modern political thought that ‘the state exists only for itself and in relation to itself, whatever obedience it may owe to the other systems like nature or God’ (Foucault 2008, 4). In this pre-modern logic of the sovereign state, the population was merely a source of power for the sovereign and the state had the power to command a sacrifice from the population for the security of the state. The state existed for itself and people existed for its protection (so went the old saying ‘save the king/queen’).

Modernity was the period in which the political state began to radically depart from this raison d’état. It brought the welfare of the population to the centre of the government. The state no longer existed for itself but for the welfare of the population. As Foucault (2000, 216–217) argues:

[p]opulation comes to appear above all else as the ultimate end of government. In contrast to sovereignty, government has as its purpose not the act of government itself, but the welfare of the population, the improvement of its condition, the increase of its wealth, longevity, health, and so on; and the means the government uses to attain these ends are themselves all, in some sense, immanent to the population; it is the population itself on which government will act either directly, through large-scale campaigns, or indirectly, through techniques that will make possible, without the full awareness of the people, the stimulation of birth rates, the directing of the flow of population into certain regions or activities, and so on. The population now represents more the end of government than the power of the sovereign; the population is the subject of needs, of aspirations, but it is also the object in the hands of the government.

Biopower and disciplinary power constitute those techniques that a modern state deploys to construct the population as a collective body, to regulate it, and to ensure its welfare. Their mode of operation is corrective, rather than punitive. They operate through normalizing the human body and mind within society itself, rather than criminalizing, physically punishing, and excluding the deviant bodies from society. The sovereign laws of the state still do have a role to play, however. Disciplinary knowledge constitutes the pervasive mode of power and plays a greater role in the operationalization of the modern form of government – governmentality. Disciplines such as statistics, medicine, psychiatry, political economy, and accounting enable and enact these forms of power. Thus, knowledge is power: disciplines create a particular set of knowledge-power nexuses in which governmentality is enacted.

Disciplinary knowledge, and hence disciplinary power, constitutes disciplinary principles, disciplinary techniques, and disciplinary practices. They are the devices of control, regulation, and normalization. For example, medicine, as a discipline, constitutes a diverse range of disciplinary principles, techniques, and practices through which individuals, as patients, are examined, monitored, regulated, and controlled. Within the disciplinary contexts that medicine creates, individuals become objects – the patients – to be examined and known, to be monitored, and to be regulated using a particular set of disciplinary principles, techniques, and practices that medicine, as a discipline, prescribes. Another set of individuals, doctors, nurses, and other medical practitioners, then become subjects – those who embody, carry, and exercise the power of the discipline. In the same vein, management accounting also constitutes a set of disciplinary techniques and practices. These place individuals and groups within a series of subject-object nexuses by, for example, transforming them into employees, subordinates, cost objects, cost centres, profit centres, accountants, managers, and so on. Thus, disciplines inscribe individuals into series of power relations, i.e. relations among people (and things) posited as relations between subjects and objects. Foucault calls these processes of transforming individuals into subjects and objects ‘subjectivation’ and ‘objectivation’. Disciplinary technologies, like accounting, enable the exercise of power by creating knowledge-power relations that make subjectivation and objectivation possible.

One of the key features of this ‘discipli...